JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Year Zero: A History of 1945’

“Though so many of the complexities of World War II and ensuing changes can not easily be summarized, Buruma’s analysis of 1945 provides several enlightening answers that begin to answer the question of how and to what degree a sense of normalcy is achieved after destruction.” (Penguin Press)

By Sheila Burt (Toyama-ken, 2010-12) for JQ magazine. Sheila is a scientific writer at the Center for Bionic Medicine at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. Read more of her writing at her blog.

Consider the following historic events: the bombings of Dresden begin; Franklin D. Roosevelt dies after serving 12 years as president; the B-29 bomber Enola Gay drops “Little Boy” on Hiroshima followed days later by “Fat Man” on Nagasaki, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths, unprecedented instant destruction, and long-lasting illnesses caused by radiation exposure; after six long, bloody years, the Second World War finally ends.

Now consider that all of these events took place in 1945.

Following these milestones in the span of only a few months, how could countries so deeply entrenched in World War II return to any sense of normalcy? How do you rebuild a broken nation?

Author and journalist Ian Buruma explores these questions and postwar disorder in his latest book, Year Zero: A History of 1945.

Writing about a single year (or several months within a single year) is not new—among a few other examples, Bill Bryson recently covered the summer of 1927 in One Summer: America, 1927; in 2010; cultural critic Fred Kaplan analyzed the significance of 1959 in his book 1959: The Year Everything Changed; and in 2005, Mark Kurlansky declared 1968 as The Year that Rocked the World.

For Buruma, a Luce Professor of Democracy, Human Rights and Journalism at Bard College and the author of several books, including the novel The China Lover, 1945 may not be more significant than other years but one of the most groundbreaking for transformations. Rather than focusing on the postwar efforts of a single country, Buruma looks at the countries destroyed or nearly destroyed by the ferocity of World War II, specifically narrowing in on the postwar chaos and change in Europe and Japan. “How did the world emerge from the wreckage? What happens when millions are starving, or bent on bloody revenge?” he asks in the prologue.

JQ Magazine: Manga Review — ‘Showa 1939-1944: A History of Japan’

“Showa is an enjoyable book to read, and this volume in particular will appeal to those interested in World War II and comprehensible narratives of the political and military intrigue of the time.” (Drawn and Quarterly)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently working at Ishikawa Prefecture’s New York office while seeking opportunities with publications in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and board gaming on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

School might be out, but that doesn’t mean your educational summer reading can’t be fun. Welcome to part two of Shigeru Mizuki’s manga history of Japan during the Showa period! If you’re just tuning in or need a refresher, check out JQ’s review of the first book, Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan. This series is translated beautifully in English by none other than JET alum Zack Davisson (Nara-ken, 2001-04; Osaka-shi, 2004-06) and published in North America by Drawn and Quarterly.

Illustrious manga artist Mizuki continues his retelling of the Showa period through his mouthpiece character Nezumi-Otoko (sometimes translated as Rat Man) of GeGeGe no Kitaro fame, and in this section includes events you have no doubt heard of such as the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Midway as well as ones you probably have not such as the Japanese campaign in the Dutch East Indies and the Battle of the Coral Sea, the first true incident of carrier warfare and air-to-air combat.

Mizuki also inserts his own autobiographical story into narrative, providing both a macro historical view and micro personal view of the war. As established in the previous volume, he has portrayed himself in a pretty poor light from the get-go, a good for nothing son that is too lazy to hold a job, can’t properly attend any school, and only seems to have a strong interest in eating as much food as possible. But the humble and comical portrayal of himself should be taken with a grain of salt, as Mizuki points out himself, in this era, “If we had a little food in our bellies, it was considered a blessing….We didn’t think about the future because we didn’t have one. Hard times at home were just the tip of the iceberg. After that there was the army, where all your future holds is an unmarked grave on a godforsaken island.”

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘A True Novel’

“A True Novel remarkably depicts the sense of isolation that anyone who has lived abroad or moved to a new place experiences. It captures the very human and conflicted desires to simultaneously fit into a society while also desiring to rebel against its impositions.” (Other Press)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently working at Ishikawa Prefecture’s New York office while seeking opportunities with publications in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and board gaming on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

This is the story of a poor boy that had the misfortune to fall in love with a rich girl. A classic Gothic tale of romance transplanted and re-imagined in postwar Japan. If you like your lovers star-crossed and your antiheroes of the rags to riches variety, then you’re in for a treat with Minae Mizumura’s A True Novel. Winner of the Yomiuri Literature Prize in 2002, A True Novel is a book filled with familiar themes executed in interesting new ways. It is a re-imagining of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights in postwar Japan, with parallels among some characters, but different enough to be original and uniquely Japanese.

A True Novel is a unique and engrossing tale that brings together three seemingly unrelated characters who are united not only by a resigned sense of isolation from their surroundings but also united in their encounters and fascination with the book’s protagonist, Taro Azuma. The focus of the novel is the story of his tragic youth, a poor boy who falls in love with a rich girl, and his growing awareness that he would always be incompatible with her in the eyes of others. He flees to America, where he claws his way up from the dregs of society and overcomes the obstacles of class and wealth to become one of the richest Japanese men of his time. While we learn about his fascinating life through the three different viewpoints of the characters with their sometimes humanly biased perspectives, the book also gives insight into the complex identities of the uprooted lives of immigrants and refugees both in Japan and in America, as well as how attitudes toward them have changed over time. A True Novel remarkably depicts the sense of isolation that anyone who has lived abroad or moved to a new place experiences. It captures the very human and conflicted desires to simultaneously fit into a society while also desiring to rebel against its impositions.

Mizumura has masterfully brought to life narrators and characters from different generations, countries, and social classes, and provides fascinating insight into their lives during different periods of Japanese history. From the bleak years of Imperial Japan’s home front during the Pacific War, and the humbling postwar period, through its modern economic success, and finally to the bubble burst and recent events, Japanese modern history comes alive in an intimate and immediate way that inspires new appreciation and curiosity for the human side of history.

JQ Magazine: Film Review – JAPAN CUTS 2014 at Japan Society

Ken Watanabe (right), stars in Unforgiven, premiering July 15 at Japan Society in New York as part of their annual JAPAN CUTS film festival. (© 2013 Warner Entertainment Japan Inc.)

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama-shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle has completed a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association of New York since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City-based soccer team.

This year’s JAPAN CUTS—North America’s biggest festival of new Japanese film—kicks off July 10-20 at New York’s Japan Society, continuing its tradition of showcasing the latest films from Japan along with some special guest stars and filmmakers. This year’s highlights include Japan’s blockbuster The Eternal Zero, The Great Passage (Japan’s submission for the Academy Award last year) and the post-3/11 documentary The Horses of Fukushima. Below are three of the 28 films in this year’s lineup that were made available to JQ at press time.

Eiji Uchida’s Greatful Dead marks the latest entry in the “dark and twisted” Japanese genre. The sordid story follows Nami (Kumi Takiuchi) as she follows “solitarians” (old and psychotic loners) around Tokyo and snaps selfies with them when they die. She enters into a morbid friendship with one particular “solitarian” (Takashi Sasano) and the rest of the film explores the darker side of humanity and mental illness in modern-day Japan. Uchida also seems to be making a statement about those most marginalized in modern Japan—the young and the elderly. Japan’s youth have a staggeringly large unemployment rate while the aging demographic makes for a perilously underfunded social security system.

Also using horror conventions for social satire is Miss Zombie, taking place in a futuristic Japan where zombies can be domesticated as servants and pets. Directed by Hiroyuki Tanaka (here using the pseudonym “Sabu”), Miss Zombie follows Shara, a mail order zombie whose owner, Dr. Teramoto, feeds her rotten vegetables in exchange for domestic labor. The film takes a darker turn as she is raped by two handymen—an event that sexually arouses Dr. Teramoto. Soon, Shara’s services are no longer limited to domestic chores. Even Dr. Teramoto’s wife finds her services useful after their son drowns. Overall, Sabu brings a fresh and interesting approach to the zombie film—a far cry from the works of George A. Romero and the countless imitators he inspired.

JQ Magazine: Book Review—‘Cinema of Actuality’

“Artists often make great sociological commentators, and Furuhata’s book sheds new light on the insights of these filmmakers.” (Duke University Press)

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama-shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle has completed a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association of New York since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City-based soccer team.

Yuriko Furuhata’s Cinema of Actuality: Japanese Avant-Garde Filmmaking in the Season of Image Politics examines a turbulent and disruptive period in Japanese history. As in other areas of the world, Japan in the late 1960s-early 1970s marked an era of youthful rebellion against the establishment, in both its public and private spheres. Furuhata’s analysis examines this period through the alternative Japanese film movements going on at the time, from New Wave figures like Masahiro Shinoda, Yasuzo Masumura and Hiroshi Teshigahara, to avant-garde filmmakers like Toshio Matsumoto and Kiyoteru Hanada. However, most of the films studied in the book are by Nagisa Oshima, largely considered to be the father of the Japanese New Wave and the “Jean-Luc Godard of Japan.” By eschewing the more traditional tendencies of the directors from Japan’s Golden Age such as Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu, these directors incorporated such formalist experiments as jump cuts, disjointed angles, shaky handheld camerawork, pop music and, most importantly, the inclusion of television news footage.

Since many of these directors were relatively young, they shared the political sensitivities of the student protesters, who sanguinely staged media events to garner attention. The “season of politics” era was prominently displayed in nightly television newscasts, which covered a wide spectrum of politically disruptive events, from hijackings to hostage crises to mass student rallies and protests. The aesthetics of this new generation of film appropriated this contemporary media coverage in attempt to both reflect and critique it. By converging with other media cultures, these filmmakers engaged in a theory-filled dialog with the nature of representation itself, in effect becoming simultaneously media practitioners as well as theorists/critics. By making this powerful argument, Furuhata—an Assistant Professor of McGill University’s Department of East Asian Studies and World Cinema Program—forcefully disputes film scholar Noël Burch’s often-quoted notion that Japan was a cinema culture devoid of theory and serious study.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘The Guest Cat’

“This is one of many books that you simply cannot judge by its cover. At only 140 pages, The Guest Cat touches on a surprising range of interesting topics, and even if you’re not a cat person you can find a lot to like.” (New Directions)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently working at Ishikawa Prefecture’s New York office while seeking opportunities with publications in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and board gaming on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

Born in 1950, Takashi Hiraide is a talented writer across many fields including genre-bending essays and highly acclaimed poetry. His prose novel The Guest Cat (translated by Eric Selland) blends both together to produce a beautiful piece that was released in English last January. It is a winner of Japan’s Kiyama Shohei Literary Award and is a best-seller in France. This is one of many books that you simply cannot judge by its cover. At only 140 pages, it touches on a surprising range of interesting topics and even if you are not a cat person, you can find a lot to like in the book. Even the narrator admits that he does not consider himself a cat lover:

“There are a few cat lovers among my close friends, and I have to admit that there have been moments when that look of excessive sweet affection oozing from around their eyes has left me feeling absolutely disgusted. Having devoted themselves to cats body and soul, they seemed at times utterly indifferent to shame. When I think about it now, rather than my not being a cat lover, it may simply have been that I feel a disconnect with people who were cat lovers. But more than anything, I’d simply never experienced having one around.”

That is not to say that Chibi, the titular guest cat, is not lovable; on the contrary, she charms everyone she meets, but do not pass on this small gem of a book thinking it is simply a chronicle of an owner doting on his pet. It is better considered a story of how a special cat brings light and life into the minds of the humans that are blessed to have her company.

“With wit and humor, Miyazaki offers insight from his long career with every turn of the page. Like an unforgettable sunset or the first time a cooking experiment came out well, he discusses experiences that leave you unexpectedly changed.” (VIZ Media)

By Alexis Agliano Sanborn (Shimane-ken, 2009-11) for JQ magazine. Alexis is a graduate of Harvard University’s Regional Studies—East Asia (RSEA) program, and currently works as an executive assistant at Asia Society in New York City.

I consider myself an aficionado of director and animator Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli. Having seen his work countless times, visited the museum in Tokyo and done a fair amount of supplemental reading, I figured Turning Point—a collection of Miyazaki interviews and articles spanning 1997 through 2008 and newly translated by Beth Cary and Frederik L. Schodt—would probably be a rehash of the similar. I presumed it would be a book for Japan or anime specialists. On the back cover there’s even a quote from the L.A. Times: “Essential reading for anyone interested in Japanese or Western animation.” However, this statement is entirely too narrow and ultimately misleading.

In fact, the book (which is a sequel to Starting Point: 1979-1996, also translated by Cary and Schodt and now available in paperback) is less about animation and Japan than it is the human condition and those existential questions that keep you awake at night. Miyazaki, at one moment reserved and the other candid, plunges fearlessly into complex, introspective and intellectual issues about human’s relationship with education, child-rearing, philosophy, history, art, environmentalism and war (to name a few).

He does this with a sprinkle of romanticism and a dusting with realism. Using his seemingly continual dissatisfaction with the world, Miyazaki aims to positively spark change and inspire. He insists that his films are not just flights of fancy; rather, he makes them to motivate the next generation to improve the world. “Children learn by experiencing…it is impossible to grow up without being hurt,” he writes. “Experiences like: accepting the duality of human nature, the importance of grit, conviction, and perseverance, and respecting nature and the land….For children willing to start, our films become powerful encouragement.”

JQ Magazine: Concert Review—Yoshiki Classical World Tour Dazzles San Francisco with Surprise X Japan Guest

“The night offered something for everyone in Yoshiki’s ability to merge and bring together different genres and listeners and touch the collective beating heart therein.” (Shirong Gao)

By Shirong Gao (Shiga-ken, 2005-07) for JQ magazine. A member of JETAA Northern California, Shirong is a graphic designer, Illustrator, and breakfast food lover who worked in a Japanese countryside as seen only in Studio Ghibli movies. For more, visit gaoshirong.com.

Every night, as a child drifting off to sleep, I looped a rock ballad. My personal lullaby. A song by multi-million-selling heavy metal band X Japan, the Rising Sun’s answer to KISS. Yet not even in dreams did I see myself growing up to one day meet its leader, Yoshiki, and witness how far he’s come in his career.

A classically trained musician turned rock legend, Yoshiki has now returned to his more refined roots, embarking on a world tour of Yoshiki Classical concerts featuring music from the eponymous solo album released last year in collaboration with talents the likes of Beatles producer Sir George Martin and the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

On April 28, Davies Hall, home to the San Francisco Symphony, was packed on a Monday night to host only the second date of Yoshiki’s tour following its debut in Costa Mesa three days prior. “Definitely a different scene from a typical classical concert,” commented attendee Arisa Takahashi (Nara-ken CIR, 1991-92), who has also performed at the hall as part of the Sing Out, Davies! choral workshop. “There were people with blue hair, dressed in their frilly Lolita finery, sitting alongside classical music attendees.”

JQ Magazine: Book Review—‘Monkey Business Volume 4’

“In part, this collection is a quest. And it is a quest into questions, many of which straddle the thin lines of life, all the while hurling us through time and space, water and air, pain and pleasure, and beginnings and ends.” (A Public Space)

By Brett Rawson (Akita-ken, 2007-09) for JQ magazine. Brett is a writer, translator, and volunteer. He currently lives in New York, where he is pursuing an MFA in creative writing at The New School and is the professional development chair for the JET Alumni Association of New York. If you have job opportunities for JET alums, an interest in presenting at JETAANY’s annual Career Forum, or want to collaborate on professional endeavors, contact him at career@jetaany.org.

Meet Volume 4 of Monkey Business International: New Writings from Japan, a collection of 23 works that will take you on a wild ride through the literary landscape of Japan. In fact, it goes beyond the boundaries of Japan—as summed up by co-founders Motoyuki Shibata and Ted Goossen in the preface, Monkey Business International is “60 percent contemporary Japan, 20 percent contemporary American and British, and 20 percent modern classic Japan,” though of course not every hybrid has a categorical home.

In part, this collection is a quest. And it is a quest into questions, many of which straddle the thin lines of life, all the while hurling us through time and space, water and air, pain and pleasure, and beginnings and ends. Take for example the short story “The Man Who Turned into a Buoy” by Masatsugu Ono. The title itself seems to whisper, loosen your grip, encouraging us to suspend our disbelief and simply enjoy as our perspective gets gently nudged out of ordinary orbit.

The tale transports us to a tiny town nestled between the shoreline and the hills, which is overrun with frolicking monkeys who descend to steal food left on graves, but have been known at times to talk with villagers, and sometimes in the voice of the deceased. This town also observes the tradition of the body as a buoy—a single man tasked with the job of nakedly floating at the edge of the inlet during the day, issuing warnings to people who exit the bay. The man who turned into the buoy is the narrator’s grandfather, and his story is recounted through the grandmother in a dense dialect that is beautifully captured by translator Michael Emmerich.

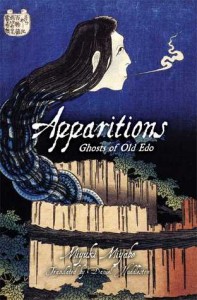

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Apparitions: Ghosts of Old Edo’

“Apparitions succeeds at not only giving historically accurate insight into the Edo period, but also delivers thought-provoking ghost stories that inspire fear and excitement with subtlety and expertly written dialogue and prose.” (Haikasoru)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently working at Ishikawa Prefecture’s New York office while seeking opportunities with publications in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and board gaming on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

Miyuki Miyabe is a Japanese author who writes widely popular fantasy, science fiction, and crime fiction for adults and young adults. Some of her works translated into English are Brave Story, ICO: Castle in the Mist, and The Book of Heroes. Published by Haikasoru last November, Apparitions: Ghosts of Old Edo is a collection of Miyabe’s short stories (translated by Daniel Huddleston) about pre-modern Japan depictions of ghosts, oni, and other supernatural events.

Apparitions includes nine short stories that are each unique but all so thoroughly engrossing that you can feel the immediacy of the narrator leaning in to deliver the chilling line foretelling the horrors yet to be revealed. Each of the stories captures the social hierarchy of the Edo period, which is a key element to illustrate in Japanese horror. One of the reoccurring aspects in Japanese ghost lore is an unbearably deep grudge that keeps a person’s spirit lingering after death. Edo society had a very rigid class system that is the source of frustration and resentment among characters, and this very resentment leads to vengeful ghost stories. This is why most ghosts in this genre are servants or women who are taking revenge on unjust masters, and insincere lovers of higher status. In this way, Japanese ghost stories are uniquely powerful in portraying the potential for wickedness in the human heart, whether it is the heart of the living or that of the vengeful dead. The supernatural dangers that appear in these stories all result from the cruel actions and thoughts of normal people that can and do occur every day. This is often exactly what is terrifying about these tales—not the ghosts, but the people.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Cool Japan: A Guide to Tokyo, Kyoto, Tohoku and Japanese Culture Past and Present’

“Cool Japan focuses on giving an inside look into the enduring and captivating qualities of Japan’s culture and history and how it can be discovered by visiting Kyoto, Tokyo, and the Tohoku region.” (Museyon Guides)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently working at Ishikawa Prefecture’s New York office while seeking opportunities with publications in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and board gaming on his blog http://brittlejules.wordpress.com and Twitter @brittlejules.

When was the last time you picked up a non-fiction book and felt like you were escaping to a faraway land? Cool Japan (Museyon Guides) is the special kind of guidebook that does just that.

The author, Sumiko Kajiyama, is a journalist and scriptwriter residing in Japan. Her other books include Ghibli Magic, The Man who Changed Animation Business, The Way of Work by Top Producers, and Important Things to Enjoy Your Work and Life.

In any bookstore you will find Frommer’s, Lonely Planet, and Fodor’s travel guidebooks. You may own a few already from trips you have taken in the past. While these guides are meticulously researched and written to suit a traveler’s needs, there is an inherent problem that they all have in common: over a relatively short amount of time, prices for services or goods can change, hostels can move or go out of business, and new ones can pop up in yet undiscovered places. For these reasons, and many that need not be mentioned, the Internet has become an invaluable tool for anyone planning a trip. Many digital communities of travelers have evolved for the exchange of current information. Furthermore, smartphones allow today’s travelers to access all of this information on the go.

So you may be wondering, why buy a guidebook at all? There are many reasons to buy the ones listed above, despite the weakness of having an ever-decaying reliability of information. Cool Japan is a special because it does not squander space listing information that may no longer be relevant by the time it gets into your hands, but instead Cool Japan focuses on giving an inside look into the enduring and captivating qualities of Japan’s culture and history and how it can be discovered by visiting Kyoto, Tokyo, and the Tohoku region.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Public Properties: Museums in Imperial Japan’

“Aso’s study is an intriguing, and refreshingly straightforward, examination of the shaping of the Japanese public in an era of increasing speed, change and modernization in the realm of how objects can promote, or even create, a national identity.” (Duke University Press)

By Jessica Sattell (Fukuoka-ken, 2007-08) for JQ magazine. Jessica is a freelance writer and a graduate student in arts journalism. Her favorite museum in all of Japan is the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, but the Mori Art Museum is a close second.

Artist Barbara Kruger poses the pinnacle of questions in an untitled 1991 photograph and type-on-paper piece featuring a sunglasses-clad man whose mouth is twisted into a howl of wonder: “Why are you here?” She provides a few suggestions: “To kill time? To get ‘cultured’? To widen your world? To think good thoughts? To improve your social life?” When this piece is encountered within the walls of a gallery or art museum, these prompts can stir the viewer to question their place as a member of a larger conversation, rather than a simple viewer or consumer. This provokes further rumination: what do we feel when we go to museums, anywhere in the world? What connections do we have, or are we “supposed” to have, to an assortment of collected and cataloged objects arranged for public access? How are we shaped by social and political entities that can (and do) organize exhibitions around certain agendas? Design, of any kind, is never without direction.

Dr. Noriko Aso, Associate Professor of History at the University of California, Santa Cruz, addresses these, and several other powerful veins of inquiry, in her recently published book Public Properties: Museums in Imperial Japan (Duke University Press). She posits that the forerunner to the Japanese museum audience of today was shaped by governing bodies in a shift that brought state-safeguarded treasures out of storage houses and into public view. In this sense, museums in Imperial Japan (1868-1945) played a part far beyond that of the cultural repository and actually took on an active role in cultivating a Japanese national identity. Artworks, ancient artifacts and other cultural treasures helped to shape the self-representation of a self-actualized Japanese public.

JQ Magazine: Film Review—Hirokazu Kore-eda’s ‘Like Father, Like Son’

“As in his other films, Kore-eda’s action unfolds in minute detail and slowly evolving scenes. His static camera and well-balanced visual frame reference Ozu, another director concerned with Japan’s modernization and the traditional family.” (© 2013 FUJI TELEVISION NETWORK, INC.AMUSE INC.GAGA CORPORATION. All rights reserved.)

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama-shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle has completed a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association of New York since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City-based soccer team.

The winner of the Jury Prize at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, Hirokazu Kore-eda’s newest film, Like Father, Like Son, features a stronger narrative arc and story than his previous films, which include the metaphysically philosophical After Life and the naturalistic Ozu-like Nobody Knows. In fact, the film’s plot reads like a Hollywood high-concept pitch: two families discover that their children are not their own due to a switch at birth. Developing a “nature vs. nurture”-type approach to the subject, Kore-eda gives the families different socioeconomic backgrounds.

Ryota Nonomiya (Masaharu Fukuyama) is a high-achieving architect who lives in a modern Tokyo high-rise apartment with his wife Midori and their six-year-old son Keita (Keita Ninomiya). The other father, Yudai Saiki (Lily Franky), is a working class shopkeeper who lives on the outskirts of the city in a nondescript housing block with his wife Yukari (Yoko Maki) and the young Ryusei (Hwang Sho-gen). By presenting these two disparate backgrounds, Kore-eda examines the nature of father-son relationships and familial influence in modern Japan.

Much of the film’s action concerns the responses to the shocking new information. Do the families try and “switch” the children again so that the original wrong can be corrected? Now that they are inseparably involved in each others’ lives, do they try and raise the children together? Or do they simply carry on as before, complicit in their knowledge that neither child is living with his biological parents? Kore-eda examines each of these scenarios as the characters try to confront a situation that life has not prepared them for.

JQ Magazine: Manga Review — ‘Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan’

“If you enjoy or are interested in manga, history and yokai, or if you appreciate excellent works such as Barefoot Gen and Maus, then Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan and the rest of the series is a must-read.” (Drawn and Quarterly)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently seeking opportunities with publications in New York. You can follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and board gaming on Twitter @brittlejules.

Shigeru Mizuki is a world-famous manga artist and writer best known for his work on yokai, which deals with Japanese ghosts, monsters and supernatural stories. He is the creator of Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro, his most famous work about yokai, and he is also well known and respected in Japan for his autobiographical work about growing up and serving as as a soldier in World War II-era Japan. He created a well researched historical and autobiographical manga about the Showa period which received the Kodansha Manga Award in 1990 and is now being published in English by Drawn and Quarterly. The first of four volumes, Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan, was translated by JET alum Zack Davisson (Nara-ken, 2001-04; Osaka-shi, 2004-06) and released last November. (For more on Davisson, read our exclusive JQ interview with him here.)

This illustrated history of Japan is praised for its accuracy in portraying the atrocities of the Japanese military during the Pacific War while also showing how the Japanese people themselves suffered on the home front. At 91 years old today, Mizuki has given us a complete and accurate account of an entire age that few alive today remember and that the rest never knew firsthand. The story is an important and valuable resource meant for generations of people who have not experienced the chaos of war and the despair of starvation. The manga is very much meant to educate the next generation of Japanese children about the controversial and darker parts of their history and to serve as a cautionary tale to remember in times of peace. It does not sugarcoat anything, and gives great insight into the tensions between Japan and China, North and South Korea, and other countries in Asia that persist today.

The 17th Japanese Film Festival in Australia wraps up after a mammoth tour around Australia. Eden Law (Fukushima JET 2010-2011, current member of JETAA NSW reviews some of the films that were on offer.

Is this organically-made?

This is a very Japanese melodrama, filled with messages about perseverance and dedication, themes that were common to many of this year’s film festival selection. The story of an apple farmer’s struggles to grow viable organic crops, it is actually based on a true story of Akinori Kimura and his wife Mieko Kimura, first popularized in a tv special and then a book (by the catchy title of “Kiseki no Ringo (Zettai Fukano) oh Kutsugaeshita Noka・ Akinori Kimura no Kiroku”) written about them by Takuji Ishikawa.

Son of an Aomori apple farming family, from an early age, Kimura (Sadao Abe) is shown to be an inveterate tinkerer, taking apart things to see how they work (although not so proficient on putting them back together again). Dissatisfied with the conservative and incurious mentality of his home town, he leaves for Tokyo for greater and better things, only to be ordered back to attend his own wedding arrangements to the local beauty, Mieko (Miho Kanno). Apparently this was enough to get Kimura to ditch his entire career in the city and settle down without complaints, to do the one thing he had scorned – apple farming, no doubt delighting his parents that their son is finally settling down and cleaving to his appropriate destiny. But then Kimura discovers that his young wife has a severe allergic reaction to all the chemical pesticides and fertilizers. So turning that curious tinker’s mind of his to the problem, he embarks on what will be a long and hard road to perfecting the perfect organic apple.

While the suffering and tribulations the Kimuras (they ended up having three daughters) endure are harsh, at times it seems so over the top that it veers closely into melodramatic territory. It’s hard to believe that the very young children shared in the suffering of their parents, for example, a sentiment echoed by Kimura’s best friend who at one point berate him severely for neglecting his daughter’s needs in a “selfish” pursuit of his dream. They have no electricity, nothing to eat, and Kimura has to take odd jobs in Tokyo to keep the family going, before losing it in a mugging – one disaster upon another. Abe’s portrayal of Kimura is also problematic, as the actor, whose cheerful face, while expressive enough to show a measure of unease beneath that ever-present smile, sometimes hits the wrong note and fails to convey the appropriate emotion that particular scenes call for. In these instances, Abe just seems at best a slightly confused person who knows that something is wrong but not entirely sure what, thereby lessening the emotional impact. It does admittedly, bring an extra level of tragedy to Kanno’s role as the long-suffering wife, who for whatever reason, continuously supports her husband through thick and thin; her acting range is decidedly broader and richer in depth. Tsutomu Yamazaki, as the wise father-in-law, in contrast, radiates such presence and dignity without having to do very much that he threatens to steal every scene he’s in. He’s the kind of strong, silent parental type that everyone wishes they have in real life.

However, it’s undeniable that it is quite a compelling story, and the Kimuras are such sympathetic characters that you can’t help but become invested in their struggles. The locations are extraordinarily beautiful, with Mt Iwaki in the background. And while I can’t be sure, I think the dialogue were spoken in Tohoku dialect, a delightful detail since I had lived in Tohoku for a time, and it certainly reinforces the bucolic country setting. Chosen to close the 17th Japanese Film Festival, it is an appropriate choice that echoes the festival’s theme of discipline, endurance and cooperation.

Fruits of Faith (Kiseki no Ringo) by Yoshihiro Nakamura, released June 8 2013 in Japan, starring Sadao Abe, Miho Kanno, Hiroyuki Ikeuchi, Takashi Sasano, Masato Ibu, Mieko Harada and Tsutomu Yamazaki.