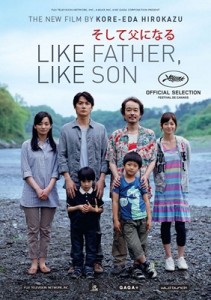

JQ Magazine: Film Review—Hirokazu Kore-eda’s ‘Like Father, Like Son’

“As in his other films, Kore-eda’s action unfolds in minute detail and slowly evolving scenes. His static camera and well-balanced visual frame reference Ozu, another director concerned with Japan’s modernization and the traditional family.” (© 2013 FUJI TELEVISION NETWORK, INC.AMUSE INC.GAGA CORPORATION. All rights reserved.)

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama-shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle has completed a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association of New York since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City-based soccer team.

The winner of the Jury Prize at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, Hirokazu Kore-eda’s newest film, Like Father, Like Son, features a stronger narrative arc and story than his previous films, which include the metaphysically philosophical After Life and the naturalistic Ozu-like Nobody Knows. In fact, the film’s plot reads like a Hollywood high-concept pitch: two families discover that their children are not their own due to a switch at birth. Developing a “nature vs. nurture”-type approach to the subject, Kore-eda gives the families different socioeconomic backgrounds.

Ryota Nonomiya (Masaharu Fukuyama) is a high-achieving architect who lives in a modern Tokyo high-rise apartment with his wife Midori and their six-year-old son Keita (Keita Ninomiya). The other father, Yudai Saiki (Lily Franky), is a working class shopkeeper who lives on the outskirts of the city in a nondescript housing block with his wife Yukari (Yoko Maki) and the young Ryusei (Hwang Sho-gen). By presenting these two disparate backgrounds, Kore-eda examines the nature of father-son relationships and familial influence in modern Japan.

Much of the film’s action concerns the responses to the shocking new information. Do the families try and “switch” the children again so that the original wrong can be corrected? Now that they are inseparably involved in each others’ lives, do they try and raise the children together? Or do they simply carry on as before, complicit in their knowledge that neither child is living with his biological parents? Kore-eda examines each of these scenarios as the characters try to confront a situation that life has not prepared them for.

What makes Like Father, Like Son more involving, however, are the deep fissures that arise in Ryota’s seemingly perfect and ordered life. A perfectionist himself, he tries to drill self-control, discipline and ambition into Keita at the expense of genuine paternal compassion. When he first meets Yudai, he disparagingly disapproves of his unsophistication and lack of ambition. Underneath the contempt, though, he begins to see a more genuine engagement with his child than he himself is capable of. It is not an exaggeration to say that throughout Keita’s short life, Ryota has failed to recognize the importance of emotional connection with his son.

It is this deeply effective exploration of his main protagonist that elevates Kore-eda’s film beyond the standard conventions of the “switched-at-birth” story. In the course of the film, implicit questions are asked, such as, “What expectations do parents place on their children?”; “Are strict, paternal discipline and emotional intimacy mutually exclusive?”; “Which is more important: emotional nurturing or preparing a child for life’s competitiveness?”; and “Can parents recognize their faults and reconcile themselves with their children?”

As in his other films, Kore-eda’s action unfolds in minute detail and slowly evolving scenes. His static camera and well-balanced visual frame reference Ozu, another director concerned with Japan’s modernization and the traditional family. Ultimately, it is Ryota’s character that is the focus of the film as he recognizes the familial sacrifices he has made on the altar of professional success. It is a phenomenon common in postwar Japan, found among the workaholic salarymen who neglect their families’ emotional needs in order to provide for them. Unlike most, however, Ryota learns to accept his familial responsibility, and, as the film’s Japanese title (Soshite Chichi ni Naru) translates, “To Become a Father.”

Like Father, Like Son opens in New York Friday, Jan. 17 at Lincoln Plaza Cinema and IFC Center. For more of Lyle’s JQ reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.