JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Issei Baseball’

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10; Kochi-ken, 2018-present) for JQ magazine. A former head of JETAA Philadelphia’s Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

The first professional baseball game involving a team of Japanese players took place in Frankfort, Kansas.

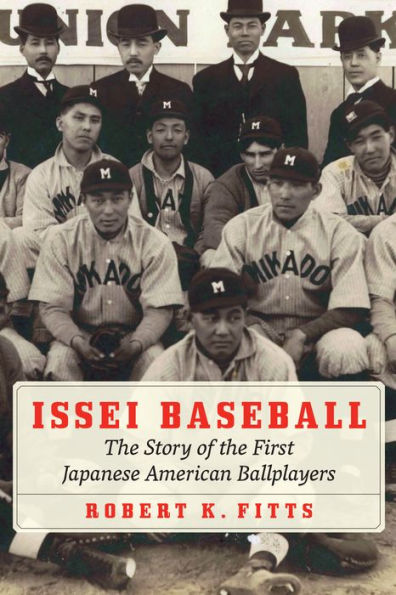

Yes, you read that correctly. That fact—and many other interesting tidbits—appear in Mashi author Robert K. Fitts’ new book Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Ballplayers, which chronicles the birth of Japanese American baseball as well as several key figures in its growth. Those figures color the early chapters, as Fitts doesn’t jump right into the tours embarked upon by Japanese American teams.

We’re treated to the stories of pioneers such as Harry Saisho, the creator of a club named the Japanese Base Ball Association (which canvassed the Midwest in 1911), Tozan Masko, the co-founder of the Mikado team (the world’s first Japanese-run professional club), and Isoo Abe, the manager Waseda University’s baseball club and organizer of its U.S. tour in 1905.

Speaking of the famous Tokyo university, Fitts devotes most of the book’s fifth and sixth chapters to that cross-country jaunt.

Such a heavy emphasis on Waseda was a bit surprising considering that on first glance Issei Baseball would focus mainly on Japanese American players in the early 20th century. It turns out their visit was a crucial part of Japanese American history, as Fitts writes: “Waseda’s visit helped establish baseball as an integral part of Japanese American culture,” with those games serving as the “first introduction to baseball for many in the community.”

A book like Issei Baseball is packed with surprises. One of them is that a prominent character in the rise of Japanese American baseball was neither Japanese nor Japanese American, but a Caucasian businessman named Guy Green, a promoter of barnstorming tours featuring Native American players in 1897 and 1898 who was awed by the extensive press coverage of Waseda’s 1905 tour and noticed the rising popularity of Japanese culture in the West. Detecting a lucrative business opportunity (many things Japanese were inexplicably trendy at that time), Green started recruiting Japanese players.

Eventually, Issei Baseball turns its focus to the whirlwind tours Green’s team undertook. Fitts does a solid job of providing accounts of memorable games played by his “Japanese Base Ball Club” (which was actually formed in Nebraska). Getting information about all the games today would be challenging since many of them were played in small towns (they did win 122 of the 142 games of which results are known), but Fitts was able to illuminate the events with lively narratives that appeared in newspapers.

Indeed, a team full of Japanese players was a major attraction in many of the towns Green’s team visited. A writer for Kansas’ Junction City Union remarked that a game between the Japanese nine and Fort Riley’s team “should prove one of the greatest baseball attractions that the vicinity has ever had the good fortune to witness.”

The information Fitts gathered from such sources is a highlight of Issei Baseball. In addition to the aforementioned quotes appearing in English-language publications, he was able to pull tidbits appearing in Japanese-language papers appearing in the early 20th century.

As Fitts dives into the lore of these pioneering figures, it’s clear that Issei Baseball examines issues beyond baseball. World War II upended the lives of most Japanese Americans, and those profiled in the book were no different. Although Fitts spends too much space on the personalities instead of the games played by various Issei teams as well as Waseda and Keio universities, it’s fascinating to learn that even embracing baseball couldn’t help Japanese Americans overcome the prejudice they faced in white society.

Issei Baseball does not shy away from addressing the racism that Issei ballplayers faced during their tours. Fitts mentions that the JBBA had to avoid playing in numerous Illinois locales due to many of them being “sundown towns.” His extensive research reveals that the Issei players were often reduced to racist stereotypes and caricatures in the media (an article in the Cincinnati Post disparaged Waseda University’s players as “little yellow men.”)

Who were those players exactly? Fitts is a historian of Japanese baseball who digs deep to reveal fascinating information about Issei players, even including an appendix with a partial roster of selected teams. Issei Baseball would have been enhanced if he could have included more information about the lives of the elite players. Reading about Keio University pitcher Kazuma Sugase (who once struck out 16 batters over 18 innings in a victory against the University of Wisconsin and, years later, was lauded by legendary New York Giants manager John McGraw as one of “one of the greatest all-around athletes in Japan,” you can’t help wanting to know more.

While baseball has a long history in Japan, the sport has just as rich of a pedigree in Japanese American communities. Issei Baseball is an encyclopedic look into a game that brought pride to a wider group of people.

For more information on Issei Baseball, click here.

For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.