JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Mashi’

“JETs reading Mashi will relate to the story because just as many of us had support systems of friendly faces outside of the workplace, Murakami was fortunate that members of the Japanese American community in both Fresno and San Francisco provided a helping hand when he needed it.” (University of Nebraska Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

During your JET experience, you probably heard about Japanese baseball icons such as Ichiro, Daisuke Matsuzaka, Hideki Matsui and Yu Darvish excelling in Major League Baseball. However, well before all of them were instilling pride in their countrymen through their feats on American diamonds, one southpaw from rural Yamanashi Prefecture was setting the big leagues on fire.

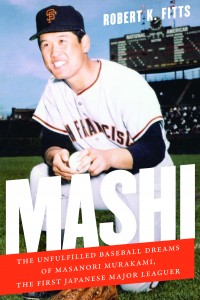

Baseball historian Robert K. Fitts introduces fans of the sport to Masanori Murakami in Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer. The biography documents how Murakami went from a run-of-the mill relief pitcher for the Nankai Hawks to a major contributor to the San Francisco Giants in the mid-1960s that nearly punched a ticket to the World Series—all while being the subject of a fierce tug-of-war between the two organizations.

Piercing together information he obtained from interviews with Murakami, the pitcher’s close friends and experts on Japanese baseball, Kitts explores Murakami’s improbable journey to baseball stardom. Murakami was actually uninterested in baseball as a child and when he did develop a deep love for the sport, his father Kiyoshi objected to his son’s new passion. But Kiyoshi relented when he realized his son could earn a scholarship to an elite Tokyo-area high school.

Despite being a high school starter, a pro career was really not on the cards for Murakami, as his main focus was on attending college (and possibly pitching at that level). However, his success at Hosei II High School made him an attractive pro prospect and representatives from several NPB (Nippon Professional Baseball) teams offered him contracts. One of those teams was the Nankai Hawks, and they offered him something more than solely the opportunity to make a lot of money: the possibility of going to the United States to improve his craft, an idea that intrigued him.

Murakami took his talents to the Osaka-based club, and following a 1963 mostly spent with the Hawks’ minor league club (he only pitched two innings in the top flight that year), he was simply told by manager Kazuto Tsuruoka that “it’s been decided that you are going to the States.” After several months in the minor leagues with the Giants’ Single-A affiliate in Fresno, Murakami was called up to the big leagues in the summer of 1964. He quickly emerged as the Giants’ go-to man in relief and became popular on both sides of the Pacific as Japanese and Japanese Americans took pride in his accomplishments on the mound. In his brief MLB career, Murakami went 5-1 during his 54 appearances and recorded nine saves.

But as indicated by the full title of the book, Murakami’s major league tenure was far from being a smooth ride. In addition to dealing with the expected language barrier and cultural differences, he lived with the uncertainty of where he would be plying his trade in 1965 as the Hawks and Giants disputed the terms of his contract with the major league club. Although Mashi is a biography, you would be forgiven for thinking a crucial part of the story is a drama—a drama that would make good entertainment on the big or small screen—due to Fitts’ portrayal of events following the 1964 season. The two chapters devoted to the saga of “will he or won’t he return to the Giants” represents the high point of the story as you feel gripped by the tension experienced by all parties in the dispute. Eventually, Murakami returned to the Hawks sooner than he would have liked due to the giri (obligation) he felt toward Tsuruoka.

Fitts excels when he educates readers on several differences between the cultures of American and Japanese baseball, such as the emphasis on team spirit seen in Japan and the brutal military-like training camps endured by players on Japanese teams. He also provides historical background on how certain aspects of baseball culture originated, and not just Japanese baseball culture. During the story, Fitts expounds on the development of relief pitching in Major League Baseball as the concept of a relief specialist was relatively recent when Murakami arrived in the U.S. (and unheard of in Japan).

While reading Mashi (so-titled because it was a nickname teammates on the minor league Fresno Giants bestowed upon Murakami), it’s striking how some of his experiences in the U.S. weren’t dissimilar to those of JETs. At times, Murakami struggled to survive on his own in a foreign country where he couldn’t speak the language—upon arriving in New York by himself to join the big league club for games against the Mets, he had no clue how to reach the team hotel and whom to meet once he arrived there. In addition, Murakami’s lack of English ability hindered his ability to understand what was happening with the Giants; when he joined the big league club, he was unaware racial tension was threatening to tear the club apart after manager Alvin Dark made inflammatory racist remarks.

But more importantly, JETs reading Mashi will relate to the story because just as many of us had support systems of friendly faces outside of the workplace, Murakami was fortunate that members of the Japanese American community in both Fresno and San Francisco provided a helping hand when he needed it. A Japanese American resident of Fresno arranged for him to stay at his family’s house when it was apparent that Murakami and two other Japanese teammates had no place to stay.

Mashi does leave some unanswered questions. Kazuto Tsuruoka enticed Murakami to sign with the Hawks by stating the club might let the young man train in the U.S. Fitts doesn’t explain why Tsuruoka would float such an idea and if it was something he did frequently. Furthermore, only a paragraph toward the end of Mashi is devoted to the U.S.-Japan Player Contract Agreement, which was signed by the MLB and NPB commissioners to prevent MLB clubs from poaching Japanese teams for their stars—effectively ensuring that no Japanese would follow Murakami to the big leagues until Hideo Nomo in the mid-1990s. That agreement was certainly a monumental event that eliminated the possibility of more Japanese starring in the big leagues. It would have been interesting to know why then-MLB commissioner William Eckert agreed to regulations that barred more elite talent from enriching his sport.

Even if politics prevented Masanori Murakami from becoming a Jackie Robinson-like figure (as well as accomplishing his goals in the major leagues), his baseball journey was a memorable one, and so is his post-diamond life: In 2004, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan awarded him a Certificate of Commendation for his contributions in “strengthening the friendship and goodwill between the U.S. and Japan.” Nine years later, he became the first former athlete to be named a goodwill ambassador for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

Mashi will take you along on his eventful ride from Yamanashi Prefecture to San Francisco.

To read an excerpt from Mashi, click here.

For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.