JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Yokohama Yankee’

“Yokohama Yankee shows how the events that precede us—the social and political movements, wars, technological advances, and natural disasters—inform our attitudes and behaviors.” (Chin Music Press)

By Michael Glumac (Miyazaki-ken, 2008-09) for JQ magazine. Michael is currently enrolled as a graduate student in international affairs, and has been a music publicist and artist manager.

Pages of Leslie Helm‘s new book Yokohama Yankee seem as though they might be perfectly at place in a Dan Brown novel, and this I mean in the most complimentary manner possible.

Really.

Helm’s non-fiction account of his family’s five generations as outsiders in Japan possess none of the mixed metaphors or historical incongruence so mocked in the Da Vinci Code author’s oeuvre. Portions of Yokohama Yankee, though, where Helm explores remote regions of Japan to uncover the story of his ancestors, possess genuine intrigue surpassing any poorly imagined scuffle with murderous druids.

In an effort to learn about his German great-great-grandfather Julius’s Japanese wife (who once stopped a sword with her bare hands), Helm enlists the help of Buddhist priests to pore over a mountain village temple’s old rice paper scrolls. From the ruins of a Roman aqueduct-like bridge, Helm identifies a mysterious abandoned island off the coast of Kyushu. Here his father engaged in a post-World War II love affair with a woman who had rumored royal connections. His exploration concludes:

“On the way back to the boat we came upon a stone monument about twelve feet high that was all but hidden by shrubs. I held the branches back while the director read the inscription carved into the stone: ‘This is to memorialize the visit of his highness…of the Imperial family.’ The aquarium director looked at me with excitement.”

Feat not, the aquarium director doesn’t turn out to be working for a secret sect of Opus Dei.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Amorous Woman’

“Amorous Woman is well written—especially the vibrant, vivid sexual acts—and you get the feeling that this would make a great film (If nothing else, there would be some hilarious scenes).” (Iro Books)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-2010) for JQ magazine. Rashaad worked at four elementary schools and three junior high schools on JET, and taught a weekly conversion class in Haguro (his village) to adults. He completed the Tokyo Marathon in 2010, and was also a member of a taiko group in Haguro.

If you were to tell stories centering on the most memorable aspects of your stay in Japan, what would you focus on?

Donna George Storey tackled the erotic. Her autobiographic eBook, Amorous Woman, brings out a side of Japan that many might not see. Inspired by Ihara Saikaku’s novel, The Life of an Amorous Woman, Storey brings to life the kinkiest aspects of her nine years in Japan, where she worked as an English teacher and a bar hostess, in addition to enjoying the company (to say the least) of countless Japanese men.

Amorous Woman actually doesn’t start in Japan but in San Francisco, where the novel’s protagonist Lydia is teaching Japanese business etiquette (despite the fact she knows little of it) to businessmen en route to the Land of the Rising Sun. But she’s actually planning to do a 180 from her life in Japan—Lydia has decided to model her life on a Japanese courtesan-turned-nun, a character that only lives in the fantasies of Ihara Saikaku. She even tells herself upon leaving Japan that she will never have sex again.

If only if it weren’t that easy to get the subject off her mind. Since she knows “plenty about picking up strangers in hot spring baths, handcuffing guys to beds in tacky love hotels,” among other things, she decides to tell the real story of her stay in Japan to two students over dinner. That’s when Amorous Woman really heats up.

Hafu: The Mixed-Race Experience in Japan premieres in New York July 28. For more information, click here.

By Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken CIR, 2000-03) for JQ magazine. Stacy is a professional Japanese writer/interpreter/translator. She starts her day by watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese, and shares some of the interesting tidbits and trends together with her own observations in the periodic series WITLife.

This weekend the annual Asian American International Film Festival will screen the new documentary Hafu: The Mixed-Race Experience in Japan (the title being the Romanization of “half” in Japanese), made by filmmakers Megumi Nishikura and Lara Perez Takagi and. Both half Japanese themselves, these women were inspired to undertake this project due to the lack of media attention on hafus and frustration with the shallow adoration of hafu celebrities on Japanese television.

The film begins with some informative statistics, such as that 2% of Japan’s population is foreign born and a striking 1 out of 49 babies is born to a family with a non-Japanese parent. These numbers have grown greatly over the last 30 years, and yet Japan is still lacking in its understanding of this diverse populace. Hafu features five half Japanese subjects, and their struggles and successes living in Japan today.

One of the families profiled is comprised of a Japanese father and a Mexican mother, who met while studying abroad in the U.S. They later married and now live in Nagoya with their two children. The older one, nine-year-old Alex, is having a hard time at his local school as the other kids tease him for being “English.” Alex’s parents believe that he needs a change in environment and decide to transfer him to an international school. He asks to spend some time in Mexico before the transition, and comes back from this trip brimming with confidence and an easing of the stutter that plagued him when he was being bullied (which his teachers had turned a blind eye to). Alex goes on to love his new school, make friends, and feel comfortable in his own skin without having to worry about being hafu.

Books: An English Language Guide to Crafting in Tokyo

Interview by Rose Symotiuk (Hokkaido 2003-2005) with Angela Salisbury, author of the Tokyo Craft Guide:

Interview by Rose Symotiuk (Hokkaido 2003-2005) with Angela Salisbury, author of the Tokyo Craft Guide:

As a JET, I keep track of my friends from my Japan days on Facebook. I started seeing posts by my fellow JETs for this cool e-book about crafting in Tokyo. Imagine my surprise when I realized that one of the authors, Angela Salisbury, was an old friend from high school!

I reached out to her to find out more about the book, crafting in Japan, and the JET crafting scene….

Rose: So, how long have you lived in Japan?

Angela: 3 years

Rose: Why did you move to Japan?

Angela: Adventure! The real answer? My husband’s job needed him in Asia, and we decided Tokyo was the place for us.

Rose: Is there an expat crafting scene in Tokyo? If so, can you tell me a little bit about it? Read More

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘From Postwar to Postmodern, Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents’

“What emerges from the multitude of ideas here is that art in Japan from this period is a visual record of repercussions that are still being felt today.” (Duke University Press)

By Jessica Sattell (Fukuoka-ken, 2007-08) for JQ magazine. Jessica is a freelance writer and a graduate student in arts journalism. She was previously the publicist for Japan-focused publishers Stone Bridge Press and Chin Music Press.

The abstract and avant-garde sculptor, painter and all-around revolutionary Japanese artist Tarō Okamoto famously said, “Art is an explostion” (geijutsu wa bakuhatsu da).

“Explosive” barely describes the energy and innovation in Japanese art in the latter half of the twentieth century. As From Postwar to Postmodern, Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents discusses, the decades between the end of World War II and the end of the Cold War marked an intensely fruitful period of groundbreaking creativity in Japan. The excitement, anxiety, and electricity that surged against the rigidity of old structures propelled Japanese art and artists into a much greater international conversation.

Published earlier this year by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and distributed by Duke University Press, this hefty tome accompanied the fall 2012-winter 2013 MoMA exhibition Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant Garde. There’s been a huge wave of both popular and scholarly interest in Japanese modern and contemporary art and dozens of high-profile shows at major North American museums and galleries, but the MoMA exhibit was the first to examine the “postwar” period that had been previously underrepresented. Part of this may be that the term “postwar” is tricky to define; the effects of WWII are undoubtedly still felt today and many argue that Japan is still “postwar.”

This book provides a solid foundation for an exploration of the issues and precedents leading up to the transformation of “postwar” art into the “postmodern” time. But, rather than simply rehash existing scholarship about Japanese history from 1945-1989, the book’s co-editors allow the artists, philosophers, critics and curators of this historical time to speak for themselves. The bulk of From Postwar to Postmodern includes a huge and multifaceted collection of primary source materials—personal essays, artist statements, interviews, magazine articles, interviews, critiques and manifestos—many of which have been translated into English for the very first time.

JQ Magazine: Film Review – JAPAN CUTS 2013 at Japan Society

Dreams for Sale premieres July 13 at Japan Society in New York as part of their annual JAPAN CUTS film festival. (© 2012 Dreams for Sale Film Partners)

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama-shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle is entering a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University (MIA 2013) and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City-based soccer team.

Now in its seventh season, the JAPAN CUTS 2013 film festival runs from July 11-21 at Japan Society in New York and features less mainstream and more art house fare than in festivals past. JQ was able to screen three films from this year’s festival: Dreams for Sale (Yume Uru Futari), Helter Skelter (Heruta Sukeruta) and A Story of Yonosuke (Yokomichi Yonosuke).

Dreams for Sale, the most affecting of the three, tells the story of a young couple, Kanya (Sadao Abe) and Satoko (Takako Matsu), who find themselves in dire straits when their restaurant burns down to the ground. They soon realize, however, that the situation allows them to seek sympathy and romance money out of lonely singles that they encounter. This morality tale is directed in a naturalistic style by Miwa Nishiwaka. Within the director’s moving frame, the two main protagonists are allowed to express themselves both fully and in nuance as they work in tandem to bilk yen out of the unsuspecting victims.

What makes the film work so well is Nishikawa’s matter-of-fact stylistic depiction; she simply allows events to unfold naturally as the camera unobtrusively records them. At first, Kanya and Satoko’s cynical schemes have a darkly comic undertone, but gradually we, as the audience, begin to see the subtle changes that the couple undergoes as they begin to first doubt the morality of what they are doing and then doubt the strength of their own marriage and relationship. As in many great tragedies, this inner turmoil spills out into the external world as their actions have unpredictable repercussions beyond their control and affect unintended innocent victims.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Persona’ and the Muddy, Dark Spiritualism of Yukio Mishima

“Starting with an almost psychoanalytic exploration of Mishima’s childhood and on to the evolution of his sexuality, political beliefs and varied artistic influences, Persona tries as much as possible to demystify the man himself and his personal contradictions.” (Stone Bridge Press)

By Sharona Moskowitz (Fukuoka-ken, 2000-01) for JQ magazine. Sharona is interested in fresh, new voices in fiction and creative nonfiction.

Who was Yukio Mishima? Persona, the lengthy new tome by Naoki Inose (the current Governor of Tokyo) and Hiroaki Sato, seeks to answer that question with the use of a comprehensive set of primary resources such as interviews, unpublished writings and personal records. Kimitake Hiraoka was on track to follow in his father and grandfather’s footsteps as a career bureaucrat at the Ministry of Finance.

In addition to his favorable lineage, he had an impressive education and just the analytical mind such a career would have required. However, he decided to turn his back on the path he had paved for himself and instead try his hand at writing a novel. And so, Yukio Mishima was born and Confessions of a Mask would become the first literary gift he conferred on Japan and eventually the world.

One of Japan’s most famous authors and infamous icons is widely remembered for his dramatic public suicide by disembowelment in downtown Tokyo, though the authors of Persona make all attempts to explore every possible aspect of Mishima’s identity without letting his sensational death overshadow his life. Starting with an almost psychoanalytic exploration of his childhood and on to the evolution of his sexuality, political beliefs and varied artistic influences, Persona tries as much as possible to demystify the man himself and his personal contradictions; he was a stickler for convention with a penchant for taboo, fiercely Japanese with an affinity for western cultures, a man both highly disciplined and simmering with unchecked passion. Read More

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies’

“The book’s release is timed to coincide with Ono’s 80th birthday on February 18, and provides readers snippets of info on some tumultuous periods during her lifetime.” (Amulet Books)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-2010) for JQ magazine. Rashaad worked at four elementary schools and three junior high schools on JET, and taught a weekly conversion class in Haguro (his village) to adults. He completed the Tokyo Marathon in 2010, and was also a member of a taiko group in Haguro.

“Everybody knows her name, but nobody knows what she does.”

That line—uttered by the most famous of her three husbands—could accurately sum up Yoko Ono for a long time. But that shouldn’t be the case. Fortunately, thanks to a new book co-written by Nell Beram and Carolyn Boriss-Krimsky, readers have insight into this remarkable woman’s life.

Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies—so titled because Ono has always looked to the sky for inspiration—delves into the life of the famous avant-garde artist and musician, from her childhood in Japan and the U.S. to her chart-topping success in her seventies. The book’s release is timed to coincide with Ono’s 80th birthday on February 18, and provides readers snippets of info on some tumultuous periods during her lifetime.

Ono’s journey is presented in an easy-to-read format geared toward young adults. Unlike many other biographies, where all the photographs tend to be lumped together in a couple of sections, the photos in Collector of Skies are spread throughout the book, and they range from one in which Ono is wearing a kimono at the age of two to another taken at the inaugural lighting of the Imagine Peace Tower in Reykjavik in 2007. The authors also use quotes from Ono to expound upon certain periods and moments of her life.

Of course, any story about Yoko Ono has to make heavy mention of her relationship with John Lennon, and the middle of the book is largely devoted to her life with the former Beatle. While Collector of Skies might not reveal anything earth shattering for hardcore Lennon and Beatles fans, younger readers (or those unfamiliar with the Beatles) will learn not just the real story of the group’s breakup, but more importantly, the duo’s activism.

“J-Boys is a historical lesson for readers of all ages. Although the story takes place 20 years after World War II, Japan is still very much scarred by the war and Oketani mentions how it affected the mindsets of the country’s people.” (Stone Bridge Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-2010) for JQ magazine. Rashaad worked at four elementary schools and three junior high schools on JET, and taught a weekly conversion class in Haguro (his village) to adults. He completed the Tokyo Marathon in 2010, and was also a member of a taiko group in Haguro.

The 1960s were a decade of enormous change around the world. Although Japan didn’t experience the upheaval some other countries did during that period, for one teenager, the mid-1960s were shaping up to be a different era.

Shogo Oketani’s novel J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965 takes readers into the lives of young Kazuo Nakamoto and, to a lesser extent, his friends—younger brother Yasuo, his friend Nobuo, Nobuo’s older brother Haruo, and Kazuo’s classmate Minoru. As steeped in tradition as Japan is (and continues to be), Oketani paints a picture of a society beginning to be seriously touched by foreign influences. Inspired by the 1964 Olympics in their hometown, Kazuo and Haruo usually head to an empty lot after school to emulate 100-meter champion Bob Hayes (It was Kazuo’s dream to be an Olympic sprinter). And like many young people across the world, Haruo went crazy for a quartet from Liverpool, often singing “A Hard Day’s Night.”

Essentially, J-Boys (which was based on Oketani’s childhood)serves a journey through the ups-and-downs of adolescence while introducing younger readers to Japanese culture and the changing landscape of the country. Kazuo’s father speaks about the rise in TV’s popularity with an air of sadness, blaming it for the loss of a nearby cinema. Likewise, Kazuo feels the new Tokyo (much of it fueled by Olympic-related construction) he sees during his Saturday afternoon walks is not necessary an improved one. Kazuo develops a crush on a girl he’s known for quite a while, but sees a couple of close friends move just prior to the start of a new school year. So he realizes he’s about to embark on an unpredictable journey.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Samurai Awakening’

“Ultimately, Samurai Awakening is a fun read that makes you think you’re watching a movie.” (Tuttle)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-2010) for JQ magazine. Rashaad worked at four elementary schools and three junior high schools on JET, and taught a weekly conversion class in Haguro (his village) to adults. He completed the Tokyo Marathon in 2010, and was also a member of a taiko group in Haguro.

For those who have lived in Japan, there were probably times when nothing seemed to be going right while struggling to get adjusted to a new culture. But eventually—or maybe miraculously—things take a 180 degree turn.

Well, that happened in Samurai Awakening, Benjamin Martin‘s work of fiction for young adults. Martin—currently a fifth year Okinawa Prefecture JET—tells the story of David Matthews, an exchange student spending the year in Japan. David is frustrated and unhappy due to the fact he can’t speak Japanese well and hasn’t made any close friends. Fittingly, very early in the story, he is bloodied in a fight with students at Nakano Junior High School.

But after attending a local temple ceremony, David learns a new god has created special powers in him. He is now able to speak Japanese fluently, fight incredibly well and turn into a cat. However, those are not the only surprises in the book. His host family the Matsumotos, who are famous sword makers, are also keeping a secret handed down to their ancestors by the Emperor of Japan. And it is with the Matsumotos that he must work to save his host sister Rie, as wolves have taken up residence in her body.

JQ Magazine: Book Reviews – ‘Belka, Why Don’t You Bark?’ and ‘The Future Is Japanese’

A pair of this year’s releases from Haikasoru.

Belka, Why Don’t You Bark?

“As a writer, Furukawa is possessed of a kinetic voice that seems to teeter on the edge of insanity. The hyperactive prose is sometimes poetic, sometimes sharp like a stinging slap in the face. Often, it’s both.” (Haikasoru)

By Sharona Moskowitz (Fukuoka-ken, 2000-01) for JQ magazine. Sharona is interested in fresh, new voices in fiction and creative nonfiction.

War: It’s a Dog’s Life. Battle Is a Bitch. War and Fleas.

These were just a few of the potential titles I had streaming through my mind as I sat down to write the review of Belka, Why Don’t you Bark?, the newly translated novel by Hideo Furukawa. But the truth is, love it or hate it (and you very well may hate it, but more on that later), Belka is far too original to be reduced to silly catchphrases or bromides.

At the very start of the novel, readers are met with a detailed canine family tree complete with the dogs’ names and nationalities. In looking back, this might as well have been a de facto warning: if anthropomorphism is not your thing, put this book down immediately.

The story begins in 1943 on the Aleutian Island of Kiska where four military dogs are left by the Japanese and then claimed by U.S. troops after the Japanese retreat. One dog dies and the other three go on to produce the offspring that populate the novel and occupy the branches of the family tree. Belka chronicles the lives of the military dogs who trace their roots back to Kiska, intertwined with the story of the young daughter of a yakuza boss who is kidnapped in the USSR and has a psychic connection to dogs. Belka is a book about history through canine eyes, namely the wars of the 20th century, as Furukawa tells us “history is moved, rolled this way and that, so simply. The twentieth century was a pawn, as were the dogs.”

JQ Magazine: Book Review – Haruki Murakami’s ‘1Q84’

“Murakami’s previous books were like delicious sandwiches that left you wanting more. 1Q84 is like a two-foot long sub that filled you to bursting, but you’re still not totally satisfied.” (Vintage International)

Roland Kelts, don’t kick me in the balls—

One man’s attempt to review a book honestly while still keeping friends

By Rick Ambrosio (Ibaraki-ken, 2006-08) for JQ magazine. A staple of the JET Alumni Association of New York (JETAANY) community, Rick manages their Twitter page and is an up-for-anything writer.

My girlfriend wouldn’t shut up about it.

“1Q84 is the best! Ah, when it comes out in English you need to read it!” Just talking about it made her rush to find her old copies (it was broken up into three books in Japan) and start reading them again. She was enthralled, to say the least. I’ve been a Murakami fan for a while: Norwegian Wood was emotional and sexually riveting; Dance Dance Dance was creepy as hell but lots of fun; Kafka on the Shore blew my mind. So I was hungry for 1Q84.

I picked it up shortly after it came out…and put it down for a while…then picked it up again…then down… then up…I think you get the idea. My feelings can kind of be summed up like this: Murakami’s previous books were like delicious sandwiches that left you wanting more. 1Q84 is like a two-foot long sub that filled you to bursting, but you’re still not totally satisfied.

The plot follows two people tied together by fate, love, and inter-dimensional happenstance. Tengo is an author and math teacher who finds himself embroiled in a shady plot to write an award-winning book. Aomame is a fitness instructor with a decidedly darker side job. Both find themselves in an altered version of 1984 called 1Q84 that deviates from the previous reality in specific ways. Those changes seem to revolve around a cult, a beautiful young girl, a book and mysterious “Little People.” Their battle to beat the odds and find each other, discover where they are, and who’s behind the changed world is an epic journey told through alternating perspectives.

1Q84 had all the things I love about Murakami: Super complex, interesting and engaging characters, crazy inter-dimensional sex, lots of mystery, and supernatural elements that bring it right on the cusp of reality, teetering between a fantasy realm and the real 1984. His ability to walk that line (like a cat walking a picket fence for those who love cats not only in Murakami novels, but also in reviews of Murakami novels) is astounding and he does it…for a really long time.

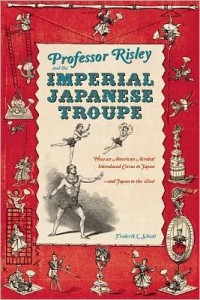

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe: How an American Acrobat Introduced Circus to Japan—and Japan to the West’

“Chock-full of illuminating illustrations and gorgeous printed ephemera that would make any contemporary typographer swoon, Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe is a jet-set adventure in pop culture scholarship sure to appeal to anyone interested in Japan’s history on the world stage.” (Stone Bridge Press)

By Jessica Sattell (Fukuoka-ken, 2007-08) for JQ magazine. Jessica is a freelance writer, and was previously the publicist for Japan-focused publishers Stone Bridge Press and Chin Music Press. She is interested in the forgotten histories of culture, and has often considered running away and joining the circus.

We’re still riding the “Cool Japan” wave that crested at the turn of the millennium, but our fascination with the country and its culture didn’t quite stem from just anime, Harajuku fashions, or J-pop. In Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe: How an American Acrobat Introduced Circus to Japan—and Japan to the West, award-winning author Frederik L. Schodt argues that contemporary interest in Japan’s popular culture has its roots in the travels and cross-cultural interactions of a band of 19th century Japanese circus performers and a colorful American impresario.

Published in November by Stone Bridge Press, Professor Risley explores a critical and exciting time in history, when an interest in foreign cultures was rapidly expanding beyond the privileged parlors of the upper class and Americans and Europeans were greatly fascinated by anything Japanese. Schodt offers an intriguing case study of both early Japanese conceptions of the West and the West’s first looks at modern Japan, but it is also a mystery of sorts: Why did a group of acrobats that were incredibly popular with international audiences in the 1860s fade from the annals of performing arts history? How was the life of “Professor” Richard Risley Carlisle, arguably one of the most extraordinarily talented and well-traveled performing artists in history, buried in the folds of time? Schodt suggests that we may never know the answers, but we can sit back and enjoy the show as their histories unfold.

This story begins, fittingly, with the question, “Where Is Risley?” Schodt artfully traces “Professor” Risley’s early travels and performance history like an elusive game of connect-the-dots, piecing together itineraries, publicity notices and press clippings until a clear pattern of a fascinating life emerges. Risley seemed to be everywhere and nowhere, and led a full life of jet-setting and adventure-seeking at a time where transcontinental travel was only beginning to open up to those outside of the diplomatic realm. We follow him on a decades-long journey across the United States, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Southeast Asia, China…and finally to Japan.

Risley arrived in Yokohama in early 1864 and immediately went to work setting up a fantastic Western-style circus to delight foreign residents and Japanese locals alike. As the country had re-opened to the world just five years earlier, it was a risky time to be in Japan, and non-Japanese residents lived with underlying worries of Shogunate-dictated expulsion and violence from disgruntled ronin. That didn’t quite stop Risley’s entrepreneurial spirit, but he did eventually run into a series of difficulties with his shows—and a stint in dairy farming, which, in the process, led him to introduce ice cream to Japan. He hadn’t originally intended to stay in Japan for long, but most likely due to the Civil War raging back home in America, he bided his time and explored his options. Thankfully, his stay there—paired with an almost desperate talent for improvisation—would lead to the world’s first taste of Japanese popular culture.

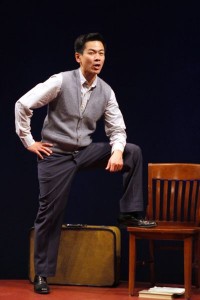

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Shukan NY Seikatsu. Visit his Examiner.com Japanese culture page here for related stories.

The opening of playwright Jeanne Sakata’s Hold These Truths begins with the famous United States Declaration of Independence quote that all men are created equal, followed by the Japanese proverb “the nail that sticks up gets hammered down.” The one hammered down is Gordon Kioyoshi Hirabayashi, the late American pacifist and Presidential Medal of Freedom honoree whose experiences in World War II-era America are brought vividly to life by Joel de la Fuente in this one-man show now running Off-Broadway.

“From the day rehearsing began for our premiere in November 2007, we’ve been working to make Hold These Truths a better play, and that hasn’t stopped with our New York premiere,” said Sakata, who shaped it through extensive interviews with Hirabayashi. The play has received positive reviews from The New Yorker and the Associated Press, and has brought wider attention to a traumatic time in American history.

Born in Seattle in 1918, Hirabayashi was imprisoned in 1942 for protesting wartime curfews. He lost a U.S. Supreme Court case the following year, but the verdict was later overturned in the 1980s, triggering an apology and reparations to the families of the more than 100,000 people interned in the western United States during the war.

Hold These Truths runs through Nov. 25 at the Theater at the 14th Street Y. For more information, visit http://epictheatreensemble.org/holdthesetruths.

JQ Magazine: Theatre Review – ‘Hold These Truths’

“This amazing life story spanning six decades manages to be compressed by playwright Jeanne Sakata into a dense 90-minute performance that both educates and entertains.” (Photo of Joel de la Fuente by Steven Boling)

A nail that stuck out but resisted being hammered down

By Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken CIR, 2000-03) for JQ magazine. Stacy is a professional writer/interpreter/translator. She starts her day by watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese, and shares some of the interesting tidbits and trends together with her own observation in the periodic series WITLife.

The intimacy of a stage surrounded by several rows of semicircle seating at the 14th Street Y is the perfect venue for the new play Hold These Truths. This work depicts the life of Nisei (second generation) Japanese American Gordon Hirabayashi, who took it upon himself to defy Executive Order 9066, which led to the imprisonment of Japanese Americans and their families in internment camps during World War II. It is a one-man show starring Joel de la Fuente, who spellbinds the audience with his ease in slipping back and forth between Hirabayashi and the other characters he portrays. The viewer’s proximity to the performer heightens the emotional depths of Hirabayashi’s often troubling, often inspiring tale of belonging and identity.

The play begins by highlighting the Japanese phrase “deru kugi wa utareru,” or “the nail that sticks up gets hammered down,” which Hirabayashi’s parents instill in him when he is young. He internalizes this belief, but at the same time he is aware of actions that seem to go against it, such as his mom taking a case to court when her land rights are violated. He describes a peaceful childhood in Seattle where he plays with other Japanese American friends and attends picnics where their mothers bring food like “onigiri, chicken teriyaki and banana cream pie.” Raised as a Christian, Hirayabashi becomes a religious pacifist when he enters the University of Washington.

Here he stays in an international dorm and meets his first non-Japanese friends, such as his roommate and close friend Howie and his future wife Esther. He becomes involved with the YMCA as campus vice president and tries to get a job with them at the front desk, but ironically is turned down because of his race. When an 8 p.m. curfew is later put in place for the Japanese, Hirabayashi initially complies but then runs back to join his friends studying in the library. This small act of bravery is emblematic of the much bolder resistance that Hirabayashi will show going forward.