JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Up from the Sea’

“If you’re interested in new perspectives of March 11, Up from the Sea is an easy read that might open eyes to the perseverance and strength of Tohoku’s residents.” (Crown Books for Young Readers)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

The afternoon of March 11, 2011 brought unprecedented destruction along the Tohoku coast and challenges that many locals have struggled to overcome even up to this day. The survivors’ stories have been told many times since then. Now, young readers get another glimpse into that day and life in the disaster-stricken area.

Inspired by a young boy she met in the disaster zone, Leza Lowitz pieces together the events of that fateful Friday to create Up from the Sea, a fictional story (although based on the events of March 11 and its aftermath) about Kai, a teenager who uses soccer to rally his community. Up from the Sea also includes a trip Kai and others made to New York to commemorate the tenth anniversary of September 11.

Lowitz writes Up from the Sea as a verse novel instead of in prose, which makes the story a much quicker and easier read. It’s divided into three major chapters—each titled after a season of the year—that document the journey from the havoc caused by Mother Nature to an enormously successful soccer game organized in the disaster-stricken community. Kai is the narrator of the story and early on, you get the feel he is setting the stage for a documentary as he provides a brief introduction to his life and the morning of March 11— until 2:46 p.m., when Japan changes forever.

JQ Magazine: Manga Review — ‘Shigeru Mizuki’s Hitler’

“Hitler is successful at educating us about the danger posed by people who can ride the waves of pain, fear, and anger in others to bring them crashing down onto the world.” (Drawn and Quarterly)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio currently keeps the lights on by working at JTB USA while writing freelance in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and comic books on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

Welcome to the most difficult book review I have ever written. Not only am I challenged to write something meaningful about a great artist’s work on a very complicated and rightfully vilified man, but I also bear a burden on my heart as I address the passing of said great artist, Shigeru Mizuki.

Last week, the world lost a much-loved cartoonist. Mizuki brought comics into the world that celebrated the strange and mysterious with unique humor and style. He brought joy to generations, young and old, with his ever popular series GeGeGe no Kitaro. He also challenged us to face and remember atrocities of war in his own country, and others, by bringing to life the war he survived through his historical manga Showa: A History of Japan, an epic work available now in English in four volumes, and a manga examination of the life of Adolf Hitler, released in English just two weeks before his passing.

We have been able to enjoy more of Mizuki’s work in the West thanks to the publishing company Drawn and Quarterly and the herculean efforts of JET Alum (and JQ interviewee) Zack Davisson (Nara-ken, 2001-04; Osaka-shi, 2004-06), who translated all four parts of Showa as well as Hitler. Davisson, a great fan of Mizuki, maintains a blog on Japanese tales, monsters, and yokai, where you can find his own work and more about the legendary cartoonist.

Justin’s Japan: ‘You Look Yummy!’

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Shukan NY Seikatsu. Visit his Examiner.com Japanese culture page here for related stories.

For parents of little ones not quite ready for Jurassic World comes You Look Yummy!, a children’s book by Tatsuya Miyanishi and newly published in English by Museyon.

The story of a fearsome Tyrannosaurus (the star of 11 other bestselling titles written by the author) and the baby Ankylosaurus he grows attached to (the tot believes his “daddy” names him “Yummy” after he’s hatched), You Look Yummy!, teaches valuable lessons about the bonds between a parent and child, and how those bonds can remain strong despite mistaken identity.

As “father” and “son” grow close, the Ankylosaurus mimics the T-Rex in ramming mountains, cutting down trees and roaring (complete with his own muted sound effects). When the day comes for them to part, readers will be touched by what unfolds.

Children will be instantly attracted to Miyanishi’s illustrations. Throughout its pages, there are artistic touches like a white sky, coloring outside the edges to make the images pop, and hash marks for the dinos that serve as texture 101. Especially effective are scenes of a night sky jam-packed with stars and dotted with some exaggeratedly large ones (think Christmas tree). The result is something that feels like it could have been drawn by a child, but is secretly the work of a seasoned artist—after all, the Tyrannosaurus is a dead ringer for Godzilla.

For more information, visit www.museyon.com.

JQ Magazine: Manga Review — ‘Showa 1953-1989: A History of Japan’

“Shigeru Mizuki has led a full life of hardship and wonder. At the time of this book’s publication, he is 93 and still bringing laughter to many through his enormous body of award-winning work, which is thankfully becoming more available in English.” (Drawn and Quarterly)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio currently keeps the lights on by working at JTB USA while writing freelance in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and comic books on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

Showa 1953-1989: A History of Japan is the fourth and final volume of the English translation of Shigeru Mizuki’s manga history of the Showa period. Translated for the first time into English by JET alum (and JQ interviewee) Zack Davisson (Nara-ken, 2001-04; Osaka-shi, 2004-06), the release of this book marks the end of a long journey for us readers. Mizuki took great pains to detail significant events of the Showa period and Japan’s role in World War II in order to preserve a comprehensive look at the time from the perspective of someone who had lived it. He intended this manga history to be a gift for all the generations born in a time of peace. As a reader born in the first year of the Heisei period, I was not even alive for any single event I read about, but nevertheless was moved by the power of Mizuki’s personal and historical storytelling and art to think about world history in new ways. The best part of reading something by Mizuki is you’re in for plenty of laughs along the way as well.

As a refresher for those of you who have been with us from the start, and an intro for those just tuning in, the first volume of this illustrated history of the Showa period in Japan covered the years 1926-1939 and highlighted a modernizing Japan and Mizuki as a child fascinated by spirits called yokai, and almost as importantly, a child obsessed with food. The book chronicled a number of incidents in Japan and Asia that took Japan down the road to World War II that come to a head in the second book which featured the years 1939-1944. This volume devotes itself to capturing the massive scale and harrowing death tolls of air-, sea-, and land-based conflicts in the war, and as time passes Mizuki’s own autobiographical narrative weaves in as he serves in the army. The third volume covers 1944-1953 and sees the darkest parts of Japanese history in World War II, and Mizuki’s own experiences are spotlighted, but it is not without the hope and admiration for humanity inspired from Mizuki’s encounter with the natives of Rabaul. This book also covers the Allied occupation of Japan and the beginning of what historians call “Postwar Japan” in which Mizuki starts down the path that will lead him to manga success and Japan becomes a booming economic power.

Interestingly, the last volume covers 1953-1989, which is 36 years of history and among the other volumes is the one that tackles the longest period of time. It’s also the most varied in its content. The same historical approach to events from a variety of perspectives narrated by either Nezumi Otoko or Mizuki himself persists through this volume, but as TV, movies, and popular culture take on an increasingly larger significance in society, so do strange events take on a more significant coloring in history. Mizuki devotes many pages to portraying abnormal events both comical and criminal that preoccupy the public mind by way of showing how times have changed since before the war. For this reason, the fourth volume at times can sometimes feel like a series of short historical episodes told in manga form, but of course presented in a chronological and unified way.

“Here Comes the Sun conveys how with persistence, perseverance and patience, seemingly impossible hurdles in Japan can be overcome.” (Stone Bridge Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

“Sometimes, you have to travel a very great distance to find a home within yourself.”

That saying could certainly describe the journey of Leza Lowitz, a Californian who has worked extensively in Japan. She chronicles her path through several eventful periods—such as adolescence during the tumultuous early 1970s, her romance with a Japanese man named Shogo (whom she eventually weds), and her attempts to adopt in Japan in Here Comes the Sun: A Journey to Adoption in 8 Chakras, an autobiographical story that captures the ups and downs of Lowitz’s efforts to carve a niche in Japanese society.

As indicated by the subtitle of the book, Lowitz utilizes the influence of another culture to best integrate herself into Japanese society. But first, you might be asking… what’s a chakra? Derived from the Sanskrit root car (“to move”), a chakra represents a major wheel of energy in the human body, and each chakra contains a particular function. Chakras regulate, distribute and balance the energy and nerve functions of their locations.

Lowitz calls the chapters in Here Comes the Sun “chakras” and each one contains a certain theme. For example, the first chapter in the book is titled Muladhara, derived from the Sanskrit word for “root” or “support.” Some chapters in Here Comes the Sun deal directly with the yoga practices that balance a chakra—Lowitz tells us when the aforementioned primary chakra is balanced, you’ll feel stable and secure while being in a better position to succeed.

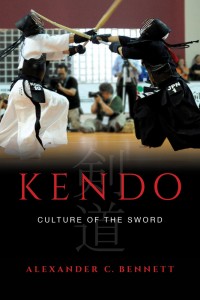

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Kendo: Culture of the Sword’

“Truly grasping Kendo might feel like learning Japanese—it’s a never-ending journey that feels overwhelming. But with persistence, the content will become easier to understand and quite enjoyable.” (University of California Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

At pep rallies for my school’s sports clubs during my time on JET, I occasionally saw students decked in armor and masks while gripping swords. They were obviously members of the kendo club, but I had no idea what they actually did (other than participate in a martial art I knew nothing about). I was excited to start reading Kendo: Culture of the Sword so I could be properly introduced to the sport.

Written by Alexander C. Bennett, a New Zealander who has served as a professor at Kansai University and the coach of his country’s national kendo team, the book illustrates how kendo has evolved throughout the years from, among other things, a form of military training to a sport in which world championships are conducted every three years. More importantly, Kendo would teach me what happens in the sport.

Indeed, my initial expectations for the book were satisfied early when Bennett explained the “complex” rules and methods of kendo (even before mentioning the rules, he does us a gigantic favor by presenting the various names for Japanese swordmanship throughout the years—kenjutsu was actually the term long used to refer to the martial art). He also shines when he includes images of the sport’s equipment as well as a table detailing how you score a point. Bennett also provides fascinating information about the state of women in kendo: although there are references to women doing kendo that date back to early modern Japan, women only largely started practicing the sport after World War II (girls were traditionally taught naginata or kyūdō instead of kendo). In addition, even though women compete nationally and internationally in championship competitions, very few women hold positions of power in kendo education at a regional or national level.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Yurei: The Japanese Ghost’

“If you like reading about mythology and supernatural horror around the world, or if you enjoy Japan’s unique brand of horror from such films as The Ring and The Grudge, then Yurei: The Japanese Ghost is a must-read.” (Chin Music Press)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently working at JTB’s New Jersey office while seeking opportunities with publications in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and board gaming on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

Do not read this review.

If you are foolish enough to read this review to the end…after seven days, you will be followed by a lingering spirit which will slowly, but unrelentingly, press more and more of its weight upon your shoulders. The weight will build to an unbearable breaking point, leaving you weak and overwhelmed by the scent of rotting flesh, driving your mind to unknowable depths of madness and despair. You can avoid this terrible fate by sharing this book review via the social media outlet of your choice or by purchasing Yurei: the Japanese Ghost, a new and excellent nonfiction effort by JET alum Zack Davisson (Nara-ken, 2001-04; Osaka-shi, 2004-06).

No doubt you’ve seen or heard of such films as The Ring and The Grudge, which have served as ambassadors of Japan’s very rich ghost culture (not to mention Halloween staples), but it is likely that there are aspects of these Japanese movies that you may have not been able to appreciate on some level. This book’s purpose is to fill in those gaps and fascinate you with an expertly catalogued evolution of ghost stories in Japan, and how pervasive they remain in pop culture to this day.

What exactly is a yūrei and why is it different from a Western ghost? What’s with the white face and long black hair? Why water? What drives the yūrei to do what it does? These questions and more are answered in this book. In the author’s words, “The goal of this book: to provide this understanding, to allow a clearer insight not only into the popular products of Japan but also the history and culture from which they sprang.” Yurei: The Japanese Ghost is a guided tour of the yūrei, from their appearance, to the rules they obey, to the traditions behind these characteristics. Davisson achieves this goal through the use of highly enjoyable primary choices and sharing the fruits of much academic research.

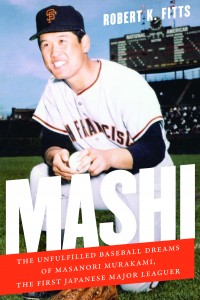

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Mashi’

“JETs reading Mashi will relate to the story because just as many of us had support systems of friendly faces outside of the workplace, Murakami was fortunate that members of the Japanese American community in both Fresno and San Francisco provided a helping hand when he needed it.” (University of Nebraska Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

During your JET experience, you probably heard about Japanese baseball icons such as Ichiro, Daisuke Matsuzaka, Hideki Matsui and Yu Darvish excelling in Major League Baseball. However, well before all of them were instilling pride in their countrymen through their feats on American diamonds, one southpaw from rural Yamanashi Prefecture was setting the big leagues on fire.

Baseball historian Robert K. Fitts introduces fans of the sport to Masanori Murakami in Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer. The biography documents how Murakami went from a run-of-the mill relief pitcher for the Nankai Hawks to a major contributor to the San Francisco Giants in the mid-1960s that nearly punched a ticket to the World Series—all while being the subject of a fierce tug-of-war between the two organizations.

Piercing together information he obtained from interviews with Murakami, the pitcher’s close friends and experts on Japanese baseball, Kitts explores Murakami’s improbable journey to baseball stardom. Murakami was actually uninterested in baseball as a child and when he did develop a deep love for the sport, his father Kiyoshi objected to his son’s new passion. But Kiyoshi relented when he realized his son could earn a scholarship to an elite Tokyo-area high school.

Despite being a high school starter, a pro career was really not on the cards for Murakami, as his main focus was on attending college (and possibly pitching at that level). However, his success at Hosei II High School made him an attractive pro prospect and representatives from several NPB (Nippon Professional Baseball) teams offered him contracts. One of those teams was the Nankai Hawks, and they offered him something more than solely the opportunity to make a lot of money: the possibility of going to the United States to improve his craft, an idea that intrigued him.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Marathon Japan’

“The running boom in Japan shows no signs of slowing. Marathon Japan explains why as it marvelously highlights a growing and evolving sport.” (University of Hawai’i Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad graduated from Leeds Beckett University with a Master’s degree in Responsible Tourism Management (for more on his life in the U.K., visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com). While in Japan, Rashaad completed the 2010 Tokyo Marathon, ran two half marathons in Yamagata Prefecture, was a part of an ekiden club, and finished fourth in the 2009 Ishidan Marathon (a race up the steps of Mount Haguro).

Hopefully, your JET experience included you busting out your running shoes and joining your prefecture (or village) in a road race. It did for me on several occasions. But if you never got around to working up a sweat over 10 kilometers (or maybe even 21), you might remember your school being enthralled by its annual ekiden, or frequently seeing races televised on Sunday mornings.

So why have such events become an integral part of Japanese sporting culture? Thomas R.H. Havens examines why in Marathon Japan, the first comprehensive English-language book about the history of marathons and ekiden in the country.

Long before Kenya emerged as the world’s elite marathon nation, Japan could make a serious claim to producing the world’s best at 42.195 km. Marathon Japan illustrates the periods when Japanese marathoners dished out most of the world’s fastest times—such as the 1930s (In 1934, nine of the world’s ten fastest times were run by Japanese), the 1960s (1965 alone saw the Japanese record fifteen of the world’s top twenty marathon times), and the 1980s (during which Toshihiko Seko won ten of the fifteen marathons he completed in). And to top it off on the women’s side, in 2004, three Japanese finished among the world’s top eight marathoners.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Monkey Business Volume 5’

“Monkey Business is a magnetic force that attracts writers who can create magical kingdoms in a single page.” (A Public Space)

By Brett Rawson (Akita-ken, 2007-09) for JQ magazine. Brett is a writer, translator, and Ramen Runner. He has an MFA in Creative Writing Non-Fiction from The New School, and his writing has appeared in Narratively and Nowhere magazine. He is also co-founder of the quarterly publication The Seventh Wave and founder of Handwritten, a place in space for pen and paper.

After reading Monkey Business Volume 5, the image of a blender might pop into your mind. Perhaps this is because it is almost summer and you have recently begun making smoothies in the early morning. Or perhaps this is because you came across the description Monkey Business as genre-defying, which made you think of cross-genre, blending boundaries, and thereafter, the physical image of the object itself: the blender.

But most likely, this is because you read the opening vignette to Monkey Business, “Photographs Are Images,” by rising Japanese writer Aoko Matsuda, which ends as such:

Everything you’ve read up to this point has been images. […] These strings of letters are images. These chains of words are images. Stories are images. The story you’re reading this very minute is an image.

Carefully selected as the opener to Volume 5, this year’s Monkey Business is all about ways of seeing, and perceiving, images and the imagination, and objects and subjects.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Gon, the Little Fox’

“Written by the legendary children’s book author Nankichi Niimi when he was just seventeen years old, the story brings to life a little rascal who never passes up a chance to cause havoc.” (Museyon)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

You probably remember reading some of Aesop’s Fables—such as “The Tortoise and the Hare” and “The Boy Who Cried Wolf”—during your childhood. Or more importantly, the lessons those fables are supposed to teach.

Likewise, your students in Japan likely read similar tales, and one of them might have been Gon, the Little Fox. Written by the legendary children’s book author Nankichi Niimi (1913-1943) when he was just seventeen years old, the story brings to life a little rascal who never passes up a chance to cause havoc, like setting fire to rapeseed husks held out in the sun, to dry to stealing a farmer’s cayenne peppers.

However, Gon realizes he’s gone too far when he kills an eel intended to be eaten by the ailing mother of a villager named Hyoju. To atone for his egregious misdeed, Gon repeatedly gathers, among other objects, mushrooms and chestnuts to leave at Hyoju’s house. But Gon’s attempts at forgiveness are never acknowledged and the story ends tragically. (Premature deaths were an unfortunate aspect of Niimi’s life; his mother passed away when he was four and he himself died when he was twenty-nine.)

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Blade’s Edge’

“While Blade’s Edge features challenges for not just the characters, it is fun to see imagination used to create fantasy in an ancient Japan from long, long ago.” (Artemis Dingo Productions)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

A lot of people (former JETs included) probably feel a lot of things take place in Japan because “that’s the way they have always been.”

So it’s not surprising that mindset would permeate throughout a fictionalized version of the country. Virginia McClain takes readers through such a place in her new novel, Blade’s Edge. Although Japan is blessed with a ridiculously long and rich history that many of us are somewhat aware of, 12th century Japan is probably a complete mystery to even most Japanophiles, but that shouldn’t stop us from imagining what it would have been like. Fortunately, McClain lets her creative and imaginary juices flow, providing readers with a glimpse of a fantasy Japan she created, inspired by her experiences living in Yamagata Prefecture and learning about the country’s history and culture.

The main characters of Blade’s Edge are two young girls named Mishi and Taka. They both reside in Gensokai, the kingdom that serves as the story’s setting (the word “Gensokai”—created from the Japanese terms for element and world—was actually coined for the purpose of the story) in addition to being a territory ruled for more than a thousand years by the Kisōshi, an elite group of warriors…who happen to be all-male.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Dreaming Spies’

“King sets up an intriguing mystery, with myriad characters with distinctive personalities coming and going, and the conclusion has satisfying twists to keep the formula from being stale.” (Bantam House)

Are detective stories your thing? What about something involving an iconic figure of literature, ninjas, and Japan? Eden Law (Fukushima-ken, 2010-11) of JETAA New South Wales reviews the new mystery novel Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. King, the latest in her Mary Russell-Sherlock Holmes series, which is partially set in Japan and delves into Japanese culture quite a bit.

Picking up another person’s work is never easy, especially if you’re continuing a series of stories long after the original, canonical work ended, and in the time since then has become so popular and well-known that it forms part of modern pop culture. This practice is nothing new and is constantly ongoing—after all, witness the prevalence and popularity (or notoriety?) of fan fiction.

A few years back, a mash-up of high and low culture saw the creation of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, which kicked off a whole slew of other entries such as Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters and Android Karenina…which shows that one way of resurrecting (pun fully intended) a story would be in the vein of a parody. However, rather than an attempt to create something interestingly imaginative (for example, repositioning the Bennet girls from helpless female chattel to arse-kicking women warriors), this genre is more cynically derivative and an attempt to cash into the zeitgeist of the lurching undead—Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, for example, will very soon be out in cinemas. Yay?

I haven’t read any of the other mash-up novels, so Dreaming Spies will be the first I’ve tackled of this growing (sub?)genre. Dreaming Spies isn’t a parody by any means, and its legendary figure of choice is one Sherlock Holmes, although the main master sleuth character here is Mary Russell, who in this story universe is the young wife of a decidedly older Holmes. Probably a wise choice, as tackling a character like Holmes would be like dating someone that just come out of a long-term relationship (i.e., someone that comes with a whole lot of baggage).

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Halfway Home: Drawing My Way Through Japan’

“Through reading her travelogue, Inzer comes across as a writer who would make an excellent travel blogger, as she gives prospective visitors to Japan fascinating tidbits about the country’s culture and attractions.” (Naruhodo Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

You may remember being treated to “What I did during my summer vacation” tales in elementary school. Well, Christine Mari Inzer spent a memorable summer vacation visiting family in Japan and she documents those travels in a largely visual journey titled Halfway Home: Drawing My Way Through Japan.

Halfway Home—so-titled because Inzer, the daughter of a Japanese mother and American father, describes herself as being half at home in the United States and half at home in Japan—summarizes her travels through a collection of photos, illustrations (all self-drawn), and anecdotes. Geared toward young adults (the author is currently a high school senior in Connecticut), Inzer details the ups and downs of travel while humorously detailing some moments of aggravation, such as her frustration with the shyness of Japanese boys.

For young people interested in eventually visiting Japan, Halfway Home provides an introduction to several of the country’s landmarks (the Daibustu in Nara, Kinkaku-ji, in Kyoto, etc.), cultural aspects, and quirks (such as the ubiquity of vending machines). Through reading her travelogue, Inzer comes across as a writer who would make an excellent travel blogger, as she gives prospective visitors to Japan fascinating tidbits about the country’s culture and attractions.

While the journal might have been enhanced a bit with the inclusion of a couple of other aspects of Japanese culture (if Inzer spent a summer in Japan, you would think she surely had to have experienced a hanabi taikai), you don’t have to be a teen to enjoy Halfway Home. Reading about her journey through Japan will surely evoke natsukashii moments for anyone who has spent a lot of time in the country.

Visit Christine’s homepage at http://christinemari.com. For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

JQ Magazine: Manga Review — ‘Showa 1944-1953: A History of Japan’

“If you enjoy or are interested in manga and history, or if you appreciate such excellent works as Maus, Persepolis or Barefoot Gen, then this series is a must-read.” (Drawn and Quarterly)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently working at Ishikawa Prefecture’s New York office while seeking opportunities with publications in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and comic books on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

Showa 1944-1953: A History of Japan is the third volume in a four-part manga history of the Showa period by eminent manga artist Shigeru Mizuki. (If you’re new to this series, check out JQ’s reviews of the first and second volumes here.)

Since I have already sung the praises of Mizuki’s excellent blending of realistic and comical art and storytelling as well as the top-notch translation by JET alum (and JQ interviewee) Zack Davisson (Nara-ken, 2001-04; Osaka-shi, 2004-06), I have decided to focus this review more on unpacking some of the contents of volume three and providing you with additional resources to look into if you wish to expand your knowledge about any of the topics that appear in the manga, including several wartime tragedies and the postwar occupation of Japan by the Allied Forces.

This volume focuses primarily on the grim latter years of World War II in the Pacific Theater. Despite the fact that Japan’s resources are running far past thin, the government and military persisted in continuing the conflict. This manga puts the spotlight on the plight of soldiers who have become the least important resource to the Japanese government, “Human life is the least valuable resource in the Japanese Army,” Mizuki writes. “Any suggestion that soldiers’ lives have meaning is tantamount to cowardice and treason. Soldiers are tools to be used. And the command’s greatest fear is that soldiers will flee from the enemy—or worse, surrender. They need them more afraid of dishonor than death.”