JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Japanese Cooking with Manga’

“Japanese Cooking with Manga is an entertaining introduction to the world of Japanese food, and an approachable book for those interested in learning more about Japanese food culture.” (Tuttle Publishing)

By Alexis Agliano Sanborn (Shimane-ken, 2009-11) for JQ magazine. Alexis is a graduate of Harvard University’s Regional Studies-East Asia (RSEA) program, and currently works as a program coordinator at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute of NYU School of Law. Additionally, she is an artist and independent filmmaker, currently working on a documentary about food education in Japan entitled Nourishing Japan.

Tuttle’s latest cookbook, Japanese Cooking with Manga, captures the ethos of creating food which suits the place you live. This quirky read was written by the Gourmand Gohan team comprised of Spaniards Alexis Aldeguer and Ilaria Mauro and Japanese-living-in-Barcelona “Maiko-san,” highlighting the universal love of Japanese food and its adaptations around the globe.

Created to be part comic book and part recipe book, this is a cookbook that you “read,” filled with colorful and humorous visual explorations of preparing Japanese food. Drawn in an artistic style more reminiscent of Tintin than Totoro, the trio guides us through visuals of chopped ingredients and simmering pots culminating in the completed meal. In truth, it would be difficult to consult the book while cooking (there’s something to be said for a more traditional layout); it’s more coffee table or bedside reading. Nevertheless, readers, especially those with an appreciation for comics, will likely enjoy this book.

In addition to recipes and narrative, the writers take care to provide background information, context and history to the world of Japanese cuisine—such as the importance of seasonal ingredients, the history of sushi, or how to identify fresh fish. For anyone embarking and revisiting the world of washoku, these principles are good reminders of the foundation to the cuisine and culture.

JQ Magazine: Film Review — ‘Kusama: Infinity’

“Clocking in at just 78 minutes, this documentary from director Heather Lenz is deceptively compact. Within its swift running time, viewers will be regaled with how Kusama overcame impossible odds to become the top-selling female artist in the world.” (Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures)

By Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken CIR, 2000-03) for JQ magazine. Stacy is a professional Japanese writer/interpreter/translator. She starts her day by watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese, and shares some of the interesting tidbits and trends together with her own observations in the periodic series WITLife.

I’ve always been an admirer from afar of Yayoi Kusama’s polka dotted and pumpkin themed artwork, but I have never waited hours in line to see it, as many New Yorkers did when her mirrored “Infinity Room” made it to the city last year. This lack of intimate knowledge regarding her work might be why I found the new film Kusama: Infinity about this amazing 89-year-old artist to be so revelatory. Clocking in at just 78 minutes, this documentary from director Heather Lenz is deceptively compact. Within its swift running time, viewers will be regaled with how Kusama overcame impossible odds to become the top-selling female artist in the world.

Born into a dysfunctional family in Matsumoto City in northern Nagano Prefecture, Kusama grew up during World War II. Her father was unfaithful and her mother’s reaction to this was to become angry and violent, even destroying Kusama’s artwork which she began creating at age 10 (The film suggests that this trauma is behind the maniacal energy that Kusama channels into her creations). Interestingly enough, her mother agreed to let her attend art school on the condition that she attend finishing school as well, but Kusama never set foot in the latter.

I had known that she spent time in New York, but the story of how she got here was fascinating. Kusama respected Georgia O’Keefe, and sent her a letter along with some of her works. After receiving a reply, in 1958 Kusama came to New York on a wing and a prayer. Before she left Japan she burned most of her early works, promising to make better ones in the future. During her time here she met legendary artists like Andy Warhol and Donald Judd, the former of whom she was distraught to later find had stolen her work. Kusama got caught up in the spirit of the 1960s counterculture and was involved in many “happenings,” such as body painting festivals and anti-war demonstrations. She even crashed the Venice Biennale exhibition in 1966 with an installation of 1,500 mirror balls on the lawn outside the pavilion, clad in a red leotard amongst them. Despite the double punch of sexism and racism that Kusama faced, she managed to make a name for herself.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Amy’s Guide to Best Behavior in Japan: Do It Right and Be Polite!’

“For JETs and others who have lived and worked in Japan, many of these rules and customs might seem very familiar and would only serve as a refresher. Yet Chavez does an excellent job of providing a clear summary of many aspects of Japanese culture—all in 144 pages.” (Stone Bridge Press)

By Andy Shartzer (Shizuoka-ken, 2014-16) for JQ magazine. Andy graduated from the University of Virginia with a degree in chemical engineering, and currently works for JETRO New York. He is also the Community Development Chair for JETAA New York.

The best part about world travel is the chance to step outside of our comfort zones and sometimes monotonous day-to-day routines to gain new and different perspectives of the world. Oh, and eat lots of amazing food, right? Not just that? Okay. Sorry, that was my stomach talking there.

In all seriousness, the chance to interact and learn from locals is an opportunity travelers should make the most of. But what if you haven’t brushed up on all the rules, customs, and etiquette of the country you’re visiting? And what if that country is Japan? And what if you’re boarding the plane now? Eesh. Well, instead of binging on reruns of Marvel movies, Amy Chavez has you covered with her new book, “Amy’s Guide to Best Behavior in Japan: Do It Right and Be Polite!” Chavez, a 25-year resident of Japan and tourist adviser who lives on Shiraishi Island (population: 600) in the Seto Inland Sea, provides a quick, easy-to-read overview of how to fully enjoy your experience in Japan and best incorporate the complexities of Japanese customs and etiquette into your homestay, study abroad, or quick jaunt to Japan. With some strong support from the educational “Amy Cat” (illustrated by Jun Hazuki), this 144-page book is the perfect reading material for your 15-hour flight.

For JETs and others who have lived and worked in Japan, many of these rules and customs might seem very familiar to you and would only serve as a refresher. Yet Chavez does an excellent job of providing a clear summary of many aspects of Japanese culture — not easy to do in 144 pages. For example, this author never quite learned the proper protocol for praying at Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, so the guidelines provided in this book (with pictures!) were very helpful. Even if you have spent a year or more as a resident in Japan, Chavez includes enough topics to ensure you learn a new thing or two — like a whole section on how to use Japanese squat toilets (Ooooh, you face the wall…who would’ve thought!).

JQ Magazine: Book Review — New from Tuttle (Summer 2018)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub–Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

Tuttle Publishing has recently released two books: one showcases the capital of Japan at its hippest and most colorful, while the other is dedicated to the traditional splendor of its castles.

“Capital of cool” sounds like an appropriate phrase to describe the host of the next Olympics. Rob Goss’s largely pictorial tribute to Tokyo certainly succeeds in making potential visitors to the capital salivate.

Subtitled Tokyo’s Most Famous Sights from Asakusa to Harajuku, Goss’s work doesn’t intend to be the typical travel guide containing useful recommendations about transportation and accommodation. Most importantly for readers, Goss provides extensive information (much of it historical) about Tokyo’s most popular tourists areas. Of course, the fun of a Tokyo trip isn’t just limited to Shibuya, Ginza, Harajuku, and the rest Goss includes segments devoted to common day trip excursion sites like Kamakura, Nikko and Yokohama.

While the photographs are obviously the first thing that jumps out at readers—indeed, Ross scores at portraying Tokyo as a youthful, vibrant city—the images are definitely not the only useful tool for prospective visitors. Several maps appear in the book, displaying places of interest that even seasoned travelers may not be aware of.

Castles are lot more than opulent fortresses to gaze at—these palaces represent an integral facet of Japanese feudal and military history.

That’s the biggest takeaway readers will get from Jennifer Mitchelhill’s Samurai Castles. Her work (complemented by photographs from David Green) provides a comprehensive introduction to two dozen of Japan’s most prominent castles. History buffs are treated to more aforementioned locales as the author then lists Japan’s 100 most important castles.

However, before seeking out what venerable fortresses might be in an off-the-beaten prefecture, the author expounds on their rich history (whose use was first recorded in an eighth-century work entitled Nihon Shoki). Architecture aficionados will appreciate the chapter dedicated to such structures, and if you’re motivated to visit one of Japan’s more prestigious castles, you’ll have some idea what you’re looking at, since Mitchelhill supplies meticulous information about each castle, as well as practical tips for prospective visitors.

For more information, visit www.tuttlepublishing.com.

For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘My Year of Dirt and Water’

“From her pottery classes to family visits, Tracy Franz takes you to a sometimes magical and sometimes complex world, but one very much full in enriching experiences.” (Stone Bridge Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub–Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

If you wrote about your year (or more) in Japan, what would you say? What stories would you tell?

Welcome to the world of Tracy Franz. An English teacher at a university in Kumamoto, she welcomes readers to her “year of dirt and water.”

My Year of Dirt and Water (the books takes its title from a line when Tracy asks herself what she hopes to accomplish while trying to recycle those two objects) is a journal-like journey of Tracy’s world. Her JET alumnus husband Koun Garrett Franz (Kumamoto-ken, 1999-01) is spending a year training as a monk in a Buddhist monastery, so Tracy must navigate the complexities of Japanese life feeling like an outsider (she mentions at one point she always feels a distance that prevents her from feeling at ease in the country).

As the book is a diary containing an entry for each day, the content runs the gamut from the mundane to the only-in-Japan moments (such as Tracy’s pottery teacher incredulously responding to the author’s being unaware of her husband’s blood type) to her observations of life in the country (Tracy concludes, to the surprise of no one, that Kyoto is a bit crowded during Golden Week and possibly not the most comfortable destination for those accustomed to the Alaskan countryside) to the creepy (like an eerie night at an onsen with a university colleague).

Of course, a journal may not be an enthralling read for some (My Year of Dirt and Water is divided into four sections each named after a season of the year while the book’s chapters each bear the name of a specific month). Remarkably, a decent portion of the book takes place in the United States, where Tracy spends much of the summer visiting her husband’s family, which has a mother-in-law battling illness.

JQ Magazine: Film Review — JAPAN CUTS 2018 at Japan Society

An “oh-my-god-it’s-too-accurate portrayal of first love” starring Aira Sunohara, Amiko makes its U.S. premiere at Japan Society July 16. (Amiko © Yoko Yamanaka)

By Katharine Olla for JQ magazine. A Friend of JET, Katharine taught as an ALT in a public elementary school in Gunma Prefecture from 2015-16. She currently works at Japan Society in New York.

It’s summer in the city, and that means another year of JAPAN CUTS, North America’s largest festival of contemporary Japanese cinema. From July 19-29, Japan Society will screen 30 films ranging from dramas and comedies to documentaries, anime, and experimental works. The festival will also feature special guest appearances by directors, documentary filmmakers, and actors, including the legendary actress Kirin Kiki, who will receive the CUT ABOVE Award for Outstanding Performance in Film.

It was difficult to choose just three to review, so I decided to watch films with strong female leads (because that’s one of the categories that Netflix tells me I like).

What if I just ran away and lived in the woods? is a question some of us ask after a morning commute on New York public transit. Get your fix by immersing yourself in the surreal, visually-striking world of Kushina, What Will You Be.

Anthropologist Soko (Yayoi Inamoto) and her assistant Keita (Suguru Onuma) trek through the forest to locate and study an elusive group said to be in the mountains. What they find is a women-only colony led by matriarch Onikuma (Miyuki Ono). Onikuma’s family consists of her daughter Kagu (Tomona Hirota) and granddaughter Kushina (Ikumi Satake), whose secret pastime is listening to her cassette player. After the outside world intrudes, how will this closed community react? And what is Kushina listening to on her Walkman?

This is Moët Hayami’s debut feature film, and it’s a labor of love: as its writer, director, art director, costume designer, and editor, with this level of care she’s managed to curate every detail of this film to create a truly singular world within a world. It’s hard to shake off after the credits roll.

Featuring an intro and Q&A with writer/director Moët Hayami and actress Tomona Hirota, Kushina, What Will You Be screens Wednesday, July 25 at 6:30 p.m. (international premiere).

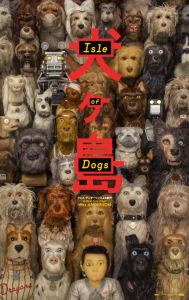

JQ Magazine: Film Review — ‘Isle of Dogs’

“Isle of Dogs is a fun film and a stylistic ode to legendary Japanese director Akira Kurosawa about a boy and man’s best friend that’s full of beautiful visuals and is equally enjoyable for both kids and adults.” (Fox Searchlight)

By Andy Shartzer (Shizuoka-ken, 2014-16) for JQ magazine. Andy graduated from the University of Virginia with a degree in chemical engineering, and currently works for JETRO New York. He is also the Community Development Chair for JETAA New York.

Isle of Dogs is director Wes Anderson’s first animated film since 2009’s Fantastic Mr. Fox. While it has received mostly positive reviews (with some reservations), it’s still interesting to see Anderson hone his storytelling skills using a colorful and vibrant world created with stop motion animation. The story opens with a prologue titled “Before the Age of Obedience” that supposedly explains how cats became more prominent in Japan. Fast forwarding to “Japan 20 Years in the Future,” the movie cuts to fictional Megasaki City, its residents, and Mayor Kobayashi (Kunichi Nomura), an authoritarian who declares that all dogs must be banished to nearby Trash Island because of the outbreak of dog flu and snout fever. The first dog that arrives on Trash Island is Spots (Liev Schreiber), the personal guard dog of Atari Kobayashi (Koyu Rankin), the ward and orphaned nephew of the mayor.

Atari soon takes matters into his own hands and flies a propeller plane to Trash Island to find Spots. He unfortunately crash lands on the island (in the meantime getting a piece of the plane stuck in his head, ouch) but is rescued by a pack of five dogs: Chief (Bryan Cranston), Boss (Bill Murray), Rex (Edward Norton), Duke (Jeff Goldblum), and King (Bob Balaban). The dogs—except for Chief, who was a former stray—agree to help Atari find Spots and accompany him on his journey to another part of Trash Island.

Though reluctant at first, Chief decides to join Atari and the other dogs after getting some extra persuasion from Nutmeg (Scarlett Johansson), a female purebred dog. Back in Megasaki City, Mayor Kobayashi orders the extermination of all dogs on Trash Island. Tracy Walker (Greta Gerwig), an American exchange student, gets involved and investigates further.

A couple fun Easter eggs in the film include: Ken Watanabe (The Last Samurai, Inception) as a head surgeon, Yojiro Noda (lead singer of RADWIMPS) as a news anchor, and Yoko Ono (artist, singer, peace activist) as a medical assistant named…Yoko Ono.

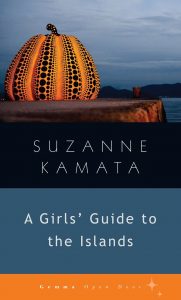

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘A Girls’ Guide to the Islands’

“While the book is largely a ‘what we did from beginning to end’ odyssey, Kamata’s vivid accounts of her journey with her daughter put you alongside them as they soak up culture.” (Gemma Open Door)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata–ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub–Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

Exploring local wonders with loved ones can conjure up magical memories—and an enormous sense of satisfaction upon overcoming numerous obstacles.

JET alumna Suzanne Kamata (Tokushima-ken, 1988-90) lived through such experiences, which are recounted in her nonfiction debut, A Girls’ Guide to the Islands. Such a title would indicate a guidebook for female travelers. But a scan of its second paragraph reveals the book is a first person travelogue of the author and her daughter Lilia’s exploration of their corner of Japan. Despite spending most of her life in the countryside, Kamata (author of Gadget Girl and The Beautiful One Has Come) has not just visited some nearby landmarks; she figures playing tourist in several locations would serve as good mother-daughter bonding experiences.

This treats the reader to a journey of art exploration. Lilia loves art and she wants to make a career out of it. Kamata also shares an affinity for art, which makes them perfect travel partners. A Girls’ Guide to the Islands is enhanced by the author’s illumination of the art she sees—such as Yayoi Kusama’s My Eternal Soul, which is painted in vivid colors that are considered unsettling in Japan (the artist’s iconic pumpkin sculpture in the island town of Naoshima also graces the book’s cover)—as well as the works that enthrall her daughter. Fortunately for them (and possibly surprising to some), foreign art from renowned artists was easy to locate in the rural museums they visited. Kamata and Lilia find one of Monet’s most famous paintings and Andy Warhol’s Flowers in Naoshima, as well as other works from other non-Japanese artists.

JQ Magazine: Film Review — ‘Mary and the Witch’s Flower’

“Director Hiromasa Yonebayashi delivers a film packed with many of the attributes that characterizes Studio Ghibli at its best.” (Universal Pictures Home Entertainment)

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama–shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle has completed a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association of New York since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City–based soccer team.

Mary and the Witch’s Flower, the debut feature film from Studio Ponoc, an anime outfit founded by Studio Ghibli veterans Hiromasa Yonebayashi and Yoshiaki Nishimura after Ghibli closed its doors in 2015, starts in medias res, with a violent firestorm engulfing the screen. A small girl with bright red hair escapes the maelstrom by flying away on a broomstick, pursued by dolphin-squid-fighter-jet hybrids. She plunges down through the clouds and crashes into a field, where her stolen cargo of glowing blue flowers scatters, instantly transforming the landscape as trees burst out of the earth to towering heights in the blink of an eye. Who she is, where she is, and why she needs to escape isn’t revealed until the final act.

Director Yonebayashi delivers a film packed with many of the attributes that characterizes Studio Ghibli at its best. In this story (based on The Little Broomstick, a 1971 children’s novel by popular British author Mary Stewart, a young female protagonist journeys through a fantastical world, battling witches on a magical quest. As in the best films of Hayao Miyazaki, the hand-drawn animation (a novelty in the CGI-dominated marketplace) depicts a European fairy tale setting while retaining a unique Japanese otherworldliness. This family-friendly film recalls such Miyazaki masterworks as Howl’s Moving Castle, Spirited Away and Kiki’s Delivery Service. Unlike those films, however, Mary and the Witch’s Flower falls short of being a masterpiece.

The animators invoke worlds upon worlds here: the green woods and mist-filled forests of England rendered in swooning evocative watercolors, and the show-stopping Endor, a psychedelic space from out of a dream or drug trip, packed with strange objects, unexplainable phenomena, students floating by in soap bubbles, fountains morphing into human form, grotesque creatures loping out of the shrubbery, only to disappear just as quickly. Endor is dazzling in an off-putting way (similar to some of the “worlds” presented in Ari Folman’s The Congress, where animated avatars engulf their originals). The action sequences are intricate and thrilling.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — New from Tuttle (Spring 2018)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata–ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub–Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

Tuttle Publishing has released another selection of Japan-related books, and the following quartet includes works that touch on Japanese etiquette, language study, Okinawan history, and picturesque Kyoto.

Japan: A Guide to Traditions, Customs and Etiquette

While studying Japanese, I learned the term shikata, which is translated as the “way of doing things.” However, as the late lecturer and writer Boyé Lafayette de Mente thoroughly documents, kata represents a lot more than a translation of “form”: It is a concept present in just about every aspect of Japanese society, whether it be the business world, poetry, or sumo. In essence, kata guides the country’s etiquette.

In Japan, the process of accomplishing a goal is just as significant, if not more significant, than the actual result—a notable contrast to the West. De Mente defines kata as the “way things are supposed to be done,” and he educates readers on how the concept has shaped Japan throughout its history and the present.

The author also touches on other cultural differences between Westerners and Japanese (such as communication styles) and people reading the book will probably nod their heads in agreement as they read certain passages, such as “Foreigners can live a lifetime in Japan and not fully understand how the Japanese system works the way it does” and why Japanese often express amazement at foreigners who can utter the simplest Japanese phrase. Japan: A Guide to Traditions, Customs and Etiquette is really an exploration of the Japanese psyche.

If nothing else, you’ll be amazing at how different Japan seems from the West.

Beginning Japanese Kanji: Language Practice Pad

Those seeking an introduction to kanji, or just a way to brush up on them, should turn to William Matsuzaki’s work. The pad is an excellent tool for busy people: The 334 kanji it presents lends itself to a simple, one kanji-a-day memorization for those aiming to study at a relaxed pace. Furthermore, each page contains terms utilizing the featured kanji and tips on how to write its strokes.

The kanji appearing in the pad is really nothing out of the ordinary, as you’ll see them in many (if not most) materials geared toward relatively novice Japanese learners. Adding to the book’s appeal, the inclusion of spaces to write the kanji (as well as sample sentences featuring the characters) is most useful for those looking to bolster their knowledge of the language.

JQ Magazine: Manga Review — ‘CITY’

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata–ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub–Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

Work often gets in the way of fun times. But if you incorporate some creativity into your life, that doesn’t have to be the case.

Enter the world of Midori Nagumo, the protagonist of the comedy manga CITY. In this first volume (which began serialization in Japan in September 2016) from creator Keiichi Arawi (Nichijou), Nagumo is a very broke college student whose landlady is constantly hounding her for money. Her roommate Niikura refuses to lend her money when she realizes what Nagumo’s true intention is.

Nagumo has to resort to other avenues to raise money, such as stealing a clay figure with the aim of selling it. But she clumsily drops the object, rendering it shattered. Crazily enough, immediately afterwards she’s offered a job at a restaurant (where the incident happens).

Our protagonist accepts the job but still has issues. It doesn’t help that her landlady has a police officer help “move” (or steal) all of her stuff so she wouldn’t escape (as the stolen items are actually collateral). In the middle of the volume, Nagumo reflects on her life, telling herself that if she could continue to have lots of happy moments, she’d be unbelievably thrilled with her life.

JQ Magazine: Theatre Review — ‘Mugen Noh Othello’

“In this striking setting, the noh theatrics perfectly capture and complement the emotions and thoughts recurring in Shakespeare’s play.” (Richard Termine)

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama–shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle has completed a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association of New York since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City–based soccer team.

From Jan. 11-14, director Satoshi Miyagi and his company Shizuoka Performing Arts Center (SPAC) returned to Japan Society of New York with their sold-out production of Mugen Noh Othello. As with their previous Madea (seen at Japan Society in 2011), Miyagi and company adapt a classic play from the Western canon and infuse it with the stylistic conventions of noh. Specifically, Miyagi and his playwright Sukehiro Hirakawa re-tell the story from the viewpoint of Desdemona’s ghost, a traditional in the mugen (supernatural) style of noh. This style typically involves otherworldly beings, including gods, spirits and ghosts. Time is often depicted as passing in a non-linear fashion, and action may switch between two or more timeframes from moment to moment, including flashbacks.

Noh theatre is considered to be the highest art form among the five classical Japanese forms of theatre: noh, kabuki, bunraku, butoh and kyogen. The art form requires highly trained actors and musicians (Mugen Noh Othello featured a percussion ensemble of six). The actors usually wear masks to signify the characters’ gender, age and social ranking, and by wearing masks the actors may portray youngsters, old men, female, or even nonhuman characters such as demons or animals. Noh also contains a uniquely structured stage with the hashigakari, a narrow bridge that is used for entering. Since Japan Society’s theater contains a more conventional stage (albeit without proscenium), the hashigakari has been approximated. All actors enter through it, as if entering from another space into the new shared theatrical space with the audience. Throughout the performance, the actors chant in unison, further accentuating the otherworldly atmosphere.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Zen Gardens and Temples of Kyoto’

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata–ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub–Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

Kyoto has served as the focal point of Japanese cultural forms such as geisha, noh theater and ikebana. And as John Dougill thoroughly details in Zen Gardens and Temples of Kyoto, the city has played an enormous role in the development of Zen in Japan.

A professor at Kyoto’s largest Buddhist university, Dougill explores the ties between Japan’s former capital and the Buddhist sect in this guide to Kyoto’s most prominent Zen gardens and temple sites. While not the birthplace of Zen in Japan, Kyoto could be considered its soul as the city has long housed renowned temples where visitors and monks have sought serenity.

At first glance, such a book would seem to be a largely visual journal featuring a score of beautiful places. Zen Gardens doesn’t disappoint in that regard as photographer John Einarsen captures the splendor of some very spiritual places. But it’s clear early on that the book will rely primarily on stories to chronicle the story of Zen in Kyoto—not surprising since Dougill has previously written about Japan’s World Heritage Sites and Kyoto’s history.

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘The JET Program and the US-Japan Relationship: Goodwill Goldmine’

“While focused solely on the American experience, the outline of the history and intention behind the JET Program’s creation is a fascinating and illuminating one. One hopes that this book will be the start of the conversation and academic study on JET’s other accomplishments and help complete the picture of a fallible but venerable institution.” (Lexington Books)

By Eden Law (Fukushima-ken, 2010-11) for JQ magazine. Eden is the current JETAA New South Wales President (in Sydney, Australia) and Australian JET Alumni Association Country Representative, and handles the social media/website side for JETAA International as Webmaster. He also runs the Life After JET podcast.

Note: Spelling is always problematic when dealing with international differences. I shall be spelling “Program” the way it is referred to in the book and the title, to avoid inconsistencies. Apologies, especially to any fellow Australians reading this. However, I’ll be keeping my quixotically placed “u”s and “r”s.

Created in 1987, The JET Program has brought tens of thousands of young people from around the world to work, live and experience life in Japan. An international exchange program of a diplomatic nature, its aims were to improve global perceptions towards Japan and to internationalised Japanese local communities, all through the format of teaching and improving English skills in schools. Since then, articles and papers about the effectiveness of JET has focused primarily on its impact (or lack thereof) on the level of English language ability on the student population, leading to questions about the feasibility of maintaining the high costs of the program. At least once, the program came close to termination: In 2010, a Japanese government budget review panel called for the discontinuation of JET, before the subsequent administration of Shinzo Abe saved it, setting the agenda for expanding numbers in the lead-up to the 2019 Rugby World Cup and the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

More positive literature exists, of course: David L. McConnell’s Importing Diversity: Inside Japan’s JET Program, published in 2000, is the most well-known example, written by an academic who was once a JET participant. Seventeen years on, Emily T. Metzgar (Shimane–ken, 1993-95), herself also once a JET and now an academic, has penned a follow-up of sorts, entitled The JET Program and the US-Japan Relationship: Goodwill Goldmine, which, as described in its title, confines its evaluation of the program on its international impact in relation to the United States and Japan. The JET Program justifies its restricted focus on this bilateral relationship on its assertion that the program was originally created with the United States in mind as the first target for Japan to improve its international image abroad. Statistically, 50 percent of the total number of participants throughout the program’s history have been sourced from the United States (and in an impeccable sense of timing, the book arrived on the eve of the program’s big 30th anniversary celebrations and JETAA conference in Washington, D.C., featuring Metzgar as one of the headline presenters).

Commentators seeking to put a more positive outlook on the program’s accomplishments have had to look outside of the hoary old topic of education. The JET Program settles on examining how it worked as a “soft power” initiative for Japan’s global image (the topic of how JET fared as an internationalisation agent of Japanese local community is, as Metzgar says, best left “as a promising research topic for an ambitious doctoral student,” though she does comment on these other aims later on). For those wondering, yes, the book argues that JET has been enormously successful in this aspect. Examples are plentiful in The JET Program: recalling the threat of JET’s culling high-profile American JET alumni in organisations such as the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and JCIE/USA defended it by referring to its “soft power” success. In other less fraught periods, the book cites senior members and policymakers of both governments who spoke positively of JET’s contributions to their countries’ relationship, implying acknowledgement of the same thing.

JQ Magazine: Film Review — ‘In This Corner of the World’

“In This Corner of the World is more than a good story with vibrant animation. It is a thoughtful work of art that holds its own against the other big anime hit of 2016, Your Name.” © Fumiyo Kouno/Futabasha/Konosekai no Katasumini Project

By Preston Hatfield (Yamanashi–ken, 2009-10) for JQ magazine. Preston is the English teacher you wish you had growing up. He taught in Kofu, Yamanashi on JET and later received his Master’s in Education and teaching credential from Stanford University. He now teaches English at a public high school in the Silicon Valley, and is inspiring the leaders of tomorrow one dank meme at a time.

Raise your hand if you remember how it felt to watch Grave of the Fireflies. It isn’t often that you’re truly glad to have watched a film that slowly rips your heart out, but the iconic 1988 film about Japan during World War II did exactly that for generations of viewers. Nearly 30 years later, director Sunao Katabuchi (Mai Mai Miracle) has created his own anime masterpiece that is every bit as poignant, tragic and beautiful as Grave of the Fireflies.

Based on the award-winning manga by Fumiyo Kouno, In This Corner of the World follows Suzu, an 18-year-old girl from Hiroshima, as she is plucked from her life by a man she only vaguely knows and moves in with his family in the nearby naval port city of Kure. As Suzu acclimates to life with her new family, the audience gets a look at the daily ins and outs of domestic life for Japanese women at the time, from tending the garden and collecting locally grown plants to make their meals, to refashioning kimonos into trousers and robes. Suzu also struggles with learning how to be a good wife and ingratiating herself to her new in-laws and her husband’s hypercritical sister.

In the latter half of the film, Katabuchi shows how the war progressively deteriorates the Japanese’s sense of normalcy, comfort, and security. What was once a quaint seaside naval town is reduced to a scene of waking nightmare and blazing fire. There are incessant air raid sirens and evacuations to bomb shelters, government propaganda, espionage hysteria, overcrowded hospitals, and the incomprehensible annihilation of cities and the people who populate them. But despite a number of somber (if not heart-wrenching) moments, In This Corner of the World ends the way most of us wish Grave of the Fireflies could have ended, and that small dose of optimism makes the film much easier to sit with when the credits roll.