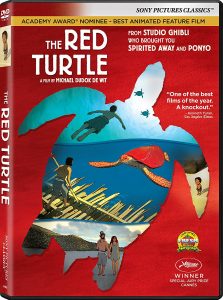

JQ Magazine: Film Review — ‘The Red Turtle’

A critical analysis couched in fiction of the Academy Award-nominated Studio Ghibli co-production (Sony Pictures Classics)

By Preston Hatfield (Yamanashi-ken, 2009-10) for JQ magazine. Preston is the English teacher you wish you had growing up. He taught in Kofu, Yamanashi on JET and later received his Master’s in Education and teaching credential from Stanford University. He now teaches English at a public high school in the Silicon Valley, and is inspiring the leaders of tomorrow one dank meme at a time.

TL;DR: Directed by Dutch animator Michaël Dudok de Wit, The Red Turtle is another visual masterpiece by Studio Ghibli (making its external co–production debut here collaborating with a European team) with a unique artistic style that makes the scenery itself a prominent character. Though it lost me in parts, the story is poignant and evokes an array of feelings, few of which are pleasant, though nonetheless life–affirming. In order to fully appreciate this film (which has no dialogue), you need to be in a calm, patient, and cerebral mood. Also, make sure you watch it in a very dark room, as the film features numerous nighttime scenes that are hard to see with extra light.

You never asked from whence I came, if I had a family in my own land, if I was happy in my new life. I suppose you found those details immaterial as far as we were concerned, but you should know that from the moment I opened my eyes and coughed the seawater from my lungs on that accursed beach we called home, after surveying the island high and low, near and far, and discovering no human civilization from which I could find salvation, I devoted every precious calorie in my body to escaping that forsaken rock, ocean be damned.

Let my words carry across time and space; to echo across the sky and go bounding beyond the reach of the island that tethered me. Let me communicate what I couldn’t before. Let my memory endure, because I have lost everything else. Let me go.

I’ll never forget the first time I saw you, a scarlet leviathan that decimated my rafts like waves over sandcastles. I admit I never quite worked it out. Was it your will or the island’s that kept me from leaving? Who did I enrage so with my escape plan and headstrong persistence in the face of constant setback? I guess what I’m asking is, were you the warden of the prison, or just one of the guards? There in the open ocean I gazed at you, awe-struck, sure in that moment that you were going to kill me for being so daring.

But that kind of cruelty is man’s domain, for it was I who translated my hate for you into violence when you came ashore, out of your element. Vulnerable. What a horrible death it must have been for a turtle. Thinking back on my actions, I am ashamed, though I cannot say that I wouldn’t do it again, for in that moment exacting my revenge was the only semblance of control I had. I took your life, and I carried that shame and guilt on my back like a shell from then on.

What happened next; was it a token of forgiveness, or had it been your intention all along? The turtle flesh within your great red shell metamorphosed into that of a young woman, and bewitched, I nursed you back to health. No word ever passed between us, but our actions spoke clearly enough. When you regained your strength, you dredged your shell into the ocean, swam it past the breakers, let it float out to sea, and I understood: You may never leave the island, but I am merciful. I will keep you company here for the rest of your days. I replied in turn, taking my half-finished fourth raft, likewise offering it to the horizon: It is freedom, not company that I desire, but what more can I do but submit to your higher power. I will accept your offering.

We grew close then. Day by day, you showed me how to live more comfortably off the island, and in our nonverbal way chatted the days into nights. We had a child together whom we loved dearly, the intersection of man and turtle, of land and sea. Our lives were simultaneously eventful and inconsequential. I will never forget the time our child, still a toddler, fell from a cliff into deep water, surrounded by sheer rock faces, and hopelessly out of reach. As I prepared to throw myself after him, you calmly gestured for him to swim down through a path between the rocks. Then, no sooner than the moment of terror had arisen, it was resolved. I think it was then that the thought first came into my head, a quote from my life before the island. The playwright William Shakespeare once wrote “Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player / That struts and frets his hour upon the stage / And then is heard no more. It is a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing.” I suppose that’s how I thought about our life then. We acted, but to no great effect. Days passed more or less the same as the ones before. We all grew older, but as our son developed muscles, I gained a progressively graying beard.

Sound and fury, signifying nothing. What better way to describe the tsunami that ravaged the island but ultimately didn’t change our lives one iota? While our son was pulling you out from under the mud and fallen trees, I was clinging to life, already half-drowned on debris that had been swept into the ocean. Truth be told, despite the desperate circumstances, I was almost euphoric then. To think, I might die away from the island after all! The tears I cried when I saw our son swimming towards me, flanked by an escort of red turtles, were bitter and sad and grateful at the same time. Our reunion was sweet. Thank heavens we were all safe—as though any of us were actually in any danger.

Shortly thereafter our son, now a man himself, came to us with the news. The ocean beckoned him, and it was time to leave his parents, as children do in many parts of the world. How I envied him, to be able to do what I never could, not only on his first try, but accompanied by his turtle friends. That was a sad moment for me, to realize that though I helped create and raise him, he had membership to a community and therefore a passport to the world that I did not. He was more your child than mine, and it hurt me terribly knowing I could never be a part of that. All the same, as I watched him leave me forever my heart was whispering: Go! Go! Leave this wretched rock for both of us!

I woke up that next morning with a hopeless feeling in my heart. I was growing weaker, my days numbered. My son had left, and when all was said and done I would be alone. How many others have there been? I understood, too late, that the island is built upon the bones of men like me. I forgive you, but even you, my love, abandoned me. When I died, you wept over my body and bore the roiling agony of mortal grief; then you resumed your turtle form and disappeared into the sea, my body left in its prison. Alone. My only hope of escape was for the tide to rise high enough to carry me away before the crabs disassembled me.

Sound and fury. It’s already far too late to matter. This is how my tragedy ends. When you see our son, tell him his old man says hi.

For more on The Red Turtle, visit http://sonyclassics.com/theredturtle.

For more JQ film reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.