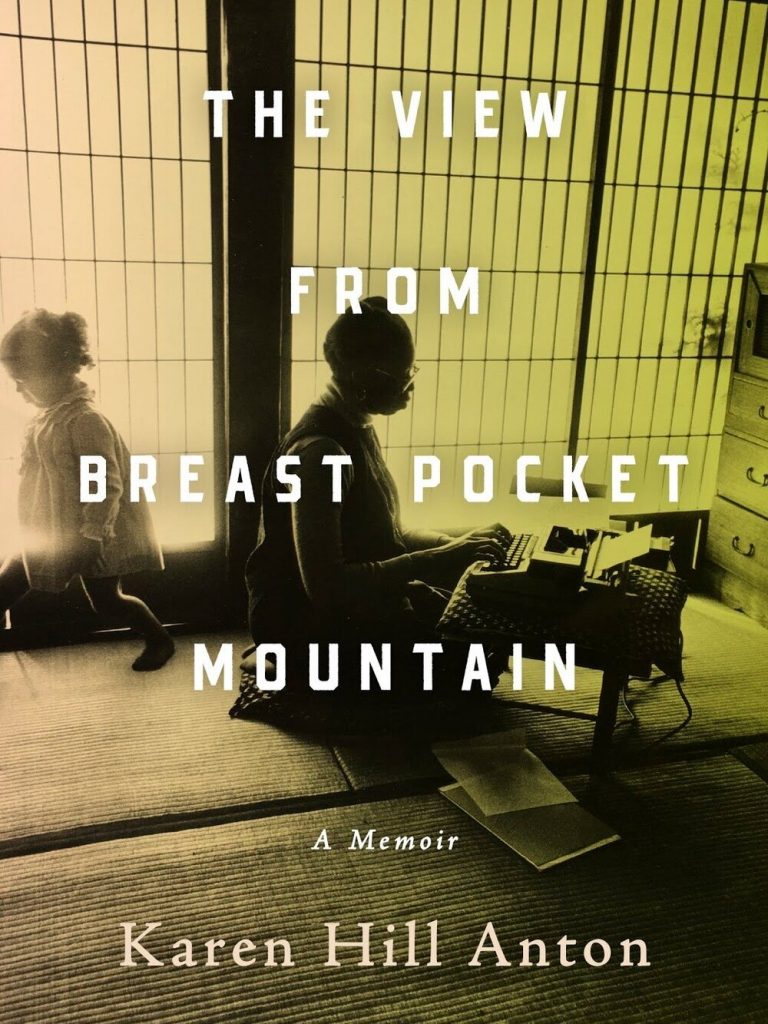

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘The View from Breast Pocket Mountain’

“Finding one’s home is often an experience. If told correctly, its story can be thrilling. The View from Breast Pocket Mountain will captivate those eager to learn more about gaikokujin who have made a home in Japan.” (Senyume Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10; Kochi-ken, 2018-2020) for JQ magazine. A former head of JETAA Philadelphia’s Sub-Chapter, Rashaad is a graduate of Leeds Beckett University with a master’s degree in responsible tourism management. For more on his life abroad and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

There are gaikokujin whose journey to Japan is quite an adventure. One of them is Karen Hill Anton. She takes readers on a tour of her unconventional life in The View from Breast Pocket Mountain: A Memoir (the mountain is the translated name of the area home of her and her husband’s farmhouse). This is a life that sees her become a columnist for two Japanese newspapers as part of a 45-year (and counting) history with her adoptive country.

Anton’s story starts in New York City, where she grew up in a tenement apartment. The author spends most of the early chapters telling stories of life in the city. Her father often struggled to find work (but did so occasionally as a presser) while her mother was institutionalized. View really takes off when Anton details the period when she traveled outside the United States for the first time. Her adventures took her around Europe (often getting around the Old Continent by sticking her thumb out), where she hung out with a cast of colorful characters, including Swedish painter and textile artist Moki Karlsson, the mother of Swedish music star Neneh Cherry.

The European portion of the book includes more than anecdotes involving interesting figures she met. Anton adroitly captures the vibe of not just a bygone era, but apparently a different planet from the United States—writing that it’s “common sense” in Denmark (where she gave birth to her first child) to put babies outside. You get the sense that she’s completely in tune with her surroundings there as she includes other fascinating tidbits about the Scandinavian country. Through her writing, she comes across as someone who can feel at home almost anywhere.

The rest of the first half of View shares more of Anton’s nomadic lifestyle—life in Switzerland, Vermont (where she worked at Goddard College), and finally traveling overland to Japan in the mid-1970s. Anton’s future husband Billy was offered an apprenticeship at a dojo in the country (he was a member of the macrobiotic community in Boston, and happened to find out that a sensei had invited three gaikokujin to live in Japan on a one-year scholarship to study yoga, martial arts, and traditional Eastern healing methods at his dojo), so it was off to Asia. The couple decided not to fly for fear of missing out on the world’s splendors. Traveling this way provided adventures, such as hatching a creative plan to cross the border in Afghanistan. Essentially, a good portion of The View is a travelogue.

Anton devotes the second half of the book to the chunk of her life sure to resonate with JET readers: her time in Japan. She illuminates the frustration she and Billy experienced at first: “There was no one at the dojo I could call a friend and I got used to being solitary,” and writes that the dojo master was prone to violent episodes (he once whacked someone with a bamboo stick because an exercise wasn’t conducted properly). However, they hoped that if they found a new location, life in the country would be more enjoyable. Billy and Karen were eventually able to do that, carving a home for themselves in Shizuoka Prefecture, moving into a rented house that Empress Teimei once spent a night in. Later, they bought land and built a house there.

View is an enjoyable read because Anton provides a perspective of a gaikokujin’s life that is different from many, if not most, JETs: Karen and Billy eventually become permanent residents of Japan, and she gives birth to three children in the country. The author documents the ups and downs of childbirth, as well as the ups and downs of her life in Japan akin to what all JETs experience. While living in the Shizuoka countryside after the birth of her second daughter, she writes that her entire world “consisted of farmhouse domestic chores and the care of children.” At that time in her Japan life, her main social interaction was joining other women for community obligations like cutting roadside weeds. At the same time, Karen details the great pride she took in the improvement she made in calligraphy, thanks to the discipline her sensei instilled in her.

Once Anton arrives in Japan, View captures the air of a memoir as well as a collection of thoughts about Japanese society. While it might be a more straightforward read if she had solely focused her story on life in Japan (you would think she would accumulate enough intriguing stories to fill roughly 290 pages), the journey around the world that Anton takes illuminates the stage for finding her literal and figurative home in East Asia. She becomes a leader in her community (being appointed the vice president of a children’s association) as well a

s a godsend for many fellow gaikokujin: In 1990, she began a column for The Japan Times (an editor suggested readers might be interested in her perspective as a foreign woman), where she often responded to readers’ calls for advice, though it wasn’t intended to be an advice column.

Finding one’s home is often an experience. If told correctly, its story can be thrilling. The View from Breast Pocket Mountain will captivate those eager to learn more about gaikokujin who have made a home in Japan, as well as those who didn’t leave upon finding out that the Japanese don’t dance at parties.

For more information on The View from Breast Pocket Mountain, click here.

For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.