WITLife is a periodic series written by professional Translator/Interpreter/Writer Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken, 2000-03). Recently she’s been watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese and sharing some of the interesting tidbits and trends together with her own observations.

Last week I had the opportunity to hear a talk given by the Japanese sociologist Dr. Yuko Kawanishi. Dr. Kawanishi has written numerous articles and is often quoted by Western media on topics such as declining birth rate, education reform, mental health and depression, family relations, juvenile crime and youth culture. She did her undergraduate work at Doshisha University and got her PhD in Sociology from UCLA. Currently she is the recipient of an Abe Fellowship and a visiting scholar at Hunter College and Columbia University’s Teacher’s College.

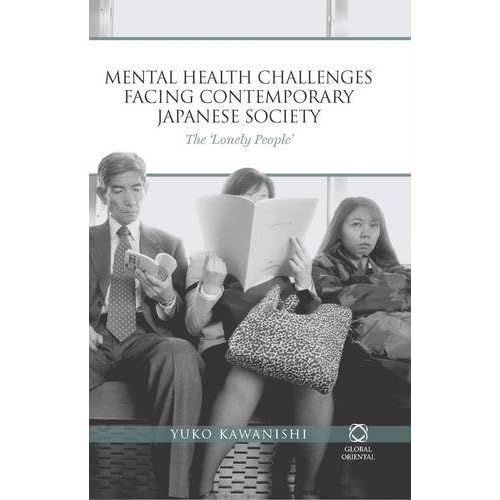

Dr. Kawanishi spoke mainly about her new book entitled “Mental Health Challenges Facing Contemporary Japanese Society: The ‘Lonely People.” It addresses the question of mental malaise in its many forms in contemporary Japanese society, focusing on three main areas: work, family and youth. These include karo-jisatsu (suicide by overwork), sekkusu-resu (sexless marriage), kateinai-rikon (in-house divorce) and hikikomori (complete social withdrawal).

She highlighted the aspects of these issues which she found to be uniquely Japanese, as well as others she saw as being universal. She explained that in Japan there had previously been a three tiered safety net in the form of family, community and work, but for the most part this no longer existed, contributing to the mental malaise. Her previous book was about families in Japan and America dealing with mental illness, and both this and her new work seem to be must reads for anyone curious about the social psychological state of the Japanese today.

The morning following her talk I was surprised to find an article in the New York Times about a retired policeman’s efforts to prevent Japanese from jumping to their death from the cliffs at a scenic spot in Fukui Prefecture. It discusses the breakdown of the work part of the safety net, citing that “suicides first surged to their recent high levels in 1998, when traditional lifetime employment guarantees began to vanish, and they have remained high as salaries and job security continued to erode.” It also mentions the fact that depression is still largely taboo in Japan, something touched on by Dr. Kawanishi as well. This makes it hard to confide in family or friends, and very often the necessary mental health resources just aren’t available.

The policeman describes his method of stopping suicides (opposed by a local tourist association that says his activities are bad for business) as approaching the likely person and gently beginning a conversation: “The person, usually a man, quickly breaks down in tears, happy to find someone to listen to his problems.” A 29-year old man who attempted suicide but was rescued and then shown further kindness by the policeman said simply, “I had no one to talk to.” Indeed, this lack of having someone to confide in whether due to stigma or availability seems to be a big stumbling block to improving Japan’s mental health services.

By the way, I love the juxtaposition of this picture (the book’s cover) with the one in the previous post. Similar subway scenes, different versions of loneliness?

one comment so far...

[…] 12/21/09: WIT Life #63: The Lonely People A post about a recent talk given in New York about loneliness in contemporary Japan. Issues “include karo-jisatsu (suicide by overwork), sekkusu-resu (sexless marriage), kateinai-rikon (in-house divorce) and hikikomori (complete social withdrawal).” An article in the New York Times noted that sometimes those suffering from depression simply have no one to talk to about their problems, and turn to suicide as the answer. […]