The 17th Japanese Film Festival in Australia is now showing in Melbourne, the last major city on its national tour before wrapping up for the year. Eden Law (Fukushima JET 2010-2011, current member of JETAA NSW reviews some of the films on offer.

I said SHUSH MF!! * machine gun fire *

Library Wars (Toshokan Senso) is the latest in a series of adaptation of an extremely popular series of light novels by Hiro Arikawa, which has included your usual manga and anime. The inspiration for the plot comes from the real life Statement on Intellectual Freedom in Libraries of the Japan Library Association, which kind of sounds pretty bad-ass when you think about it. Especially when, interpreting its mission statement rather liberally to mean the right to bear arms. Armed librarians. Hate to think what the penalties for late returns would be.

Dealing with the theme of censorship, Japan in an alternate reality has gone overboard with outlawing ‘unsuitable’ reading material, raiding shops with maniacal book-burning zeal. But against this thought police are the librarians who form the defensive Librarian force, who take up arms to protect the citizens’ right and access to information. Joining the ranks is Iku Kasahara (Nana Eikura), who is your typical rough diamond – brash, impulsive, klutzy, a rule-breaker and therefore audience favourite. She continuously butts head against hard-arse Atsushi Dojo (Junichi Okada), a no-nonsense senior librarian who naturally, questions her place in the force. Around them, forces are on the move to consolidate and destroy books and knowledge, and the Library Force gears up for the ultimate confrontation.

This isn’t Fahrenheit 451, although there are some discussions about freedom of speech and an out of control state that doesn’t know where to draw the line in the name of protecting the hearts and minds of the nation from indecency and corruption. But for the most part, it’s largely kept light and focused on comedy and action, with recognizable character tropes from Japanese fiction. While it’s a pure escapism, some things are a bit far-fetched: you wonder why no one, in the year 2019, have thought about making backups, especially if these things are so precious, for example.

The cast perform their roles as expected, their characters doesn’t have much need for complex character development. Things like character quirks that might work in a novel or an anime situation don’t translate too well into a live-action film – Kasahara’s personality isn’t that endearing, and Dojo, as handsome as he is, is rather a one-note character. There’s obviously a lot that hasn’t been transferred from a wealth of source material into the short timeframe of a film. Although I must say Jun Hashimoto’s scenery chewing is one of the entertaining things to watch in this film (it’s like each facial muscle is working independently of each other). Things pick up in the last half as it’s action-packed, but the film is largely froth and would appeal the most to the fan base. Had it been a lot funnier, I might be more forgiving of some of the plot holes, but as such, while it isn’t bad, it’s just rather pedestrian and unmemorable.

Library Wars (Toshokan Senso) by Shinsuke Sato, released April 27 2013 in Japan, starring Junichi Okada, Nana Eikura, Kei Tanaka, Sota Fukushi, Chiaki Kuriyama, Kenji Takeyama, Iwao Nishina, Ryusuke Kenta and Maki Orikuchi.

The 17th Japanese Film Festival in Australia is now showing in Melbourne, the last major city on its national tour before wrapping up for the year. Eden Law (Fukushima JET 2010-2011, current member of JETAA NSW reviews some of the films on offer.

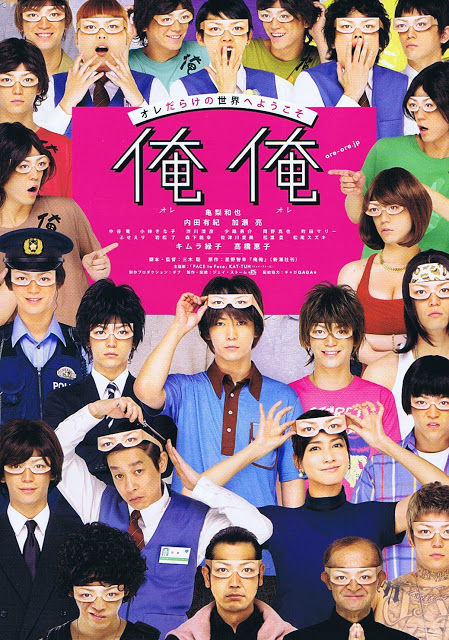

Will the real Hitoshi please stand up, please stand up?

This is film messed with my head. Escalating from a quirky, comedy of errors with eccentric characters to a disturbing, confusing movie where you feel like the character Hitoshi himself, running around wild-eyed in panic as you try to make sense of what’s going on – not that the film gives you any concrete answers.

But let’s start with a bit of a background. Hitoshi (Kazuya Kamenashi), a failed photographer, makes a living working in an electronics department, with fellow employees who are probably a little bit insane. Then one day, a stranger’s phone falls into his hands, and on impulse, Hitoshi takes the phone and scams the owner’s mother into depositing 900,000 yen into his bank account. And then that’s when shit gets weird.

The title “It’s Me, It’s Me” comes from the fact Hitoshi starts finding copies of himself popping up, each with his face but different name, different lifestyles – even of the opposite gender. It’s almost like seeing versions of himself – Kamenashi doesn’t just wear different wigs or clothes, or act differently; his face gets superimposed on wildly different body types like that scene from Being John Malkovich. Does each copy represent a possibility or alternate reality that could have been, had circumstances being different, or a choice decided in another way? Which is the real Hitoshi? Was there ever a real Hitoshi? I really don’t know – you tell me. At first finding other “me”s is fun – it’s like finding someone who truly understands you – but the initial novelty and fun of first discovery soon gives way to darker developments, as the initial group of Hitoshis realise that not every aspect of their personality is pleasant, or even desirable. Out of place objects then begin to appear in some scenes, such as overturned drums of strange viscous pink liquid crop up and disappear, posters of a pair of eyes stuck on walls appear to watch Hitoshi and his strange adventures – Miki’s mischievous and anarchic humour teases us as they appear and disappear in the film, like visual signposts of the upcoming weirdness that is about to unleash.

But in the meantime, we are distracted by the anarchic humour and fun by the assortment of characters and dialogue. Minor characters are invested with a huge amount of personality and energy, like Hitoshi’s original mum, Masae (Midoriko Kimura) who insists on being called by her name instead of “mother” because she decided it suits her more; his co-workers like the hyperactive Minami (Eri Fuse) and overbearing dorky manager Tajime (Ryo Kase) and sexy customer Sayaka (Yuki Uchida). Kamenashi juggles a huge amount of roles, portraying different minor characters who seem to be different kind of Japanese stereotypes, definitely working hard for his money.

You might find “Ore Ore” infuriating or intriguing, but it is a wild ride, throwing up all sorts of puzzling questions and frustrating vague hints as to the possible answers.

It’s Me, It’s Me (Ore Ore) by Satoshi Miki, released May 25th 2013 in Japan. Starring Kazuya Kamenashi, Yuki Uchida, Ryo Kase, Midoriko Kimura, Keiko Takahashi, Eri Fuse, Ryu Nakatani and Kinako Kobayashi.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Life in Japan: The First Year’

“Edison’s artistic talent captures Japan’s essence and his autobiographical account is honest and direct. JET Alumni will be able to follow his story and find many of their own experiences and thoughts represented within his work. From his first encounter ordering a hamburger to his dissatisfaction with being a glorified babysitter, his tone and pace keeps the reader hooked.” (Big Ugly Robot Publishing)

By Lana Kitcher (Yamanashi-ken, 2010-12) for JQ magazine. Lana is the business development associate for Bridges to Japan. To read more about Lana’s adventures in Japan and New York, visit her blog at Kitcher’s Café.

Victor Edison is a young man who remembers always having some Japanese influences present throughout his life. His family hosted a Japanese exchange student during his childhood, and he was fascinated by anime and manga from a young age. After graduation he found himself working a job he didn’t really want that wasn’t really going anywhere. A friend that was working in Japan at the time encouraged him to apply to be an English teacher and all he could respond to this was, “why not?”

Published by Nagoya-based Big Ugly Robot Press, Life in Japan: The First Year is a bilingual graphic novel written and drawn by Edison about his first year working for an English language school in Mie Prefecture. With little previous knowledge of the Japanese language or customs, he travels blindly to his new home armed only with his enthusiasm and determination to succeed, his ultimate goal to one day become a full-time artist.

His first choice was to work in Tokyo, simply because that was all he knew. After his interview with “Noba,” he soon learns that he has been offered a position in Mie, and accepts.

He starts work at an English conversation school located in a semi-rural area. While the majority of the clients were adults and young adults, the teachers often had to “teach” toddler classes as well. Because the school was located in a shopping mall, many parents would drop their kids off at the English school to fit in some uninterrupted shopping time. The teachers quickly learned that the child classes were thinly disguised babysitting sessions.

The 17th Japanese Film Festival makes its final stop in Melbourne. Eden Law (Fukushima JET 2010-2011, JETAA NSW member) reviews some of the selection available.

So what have you done with your life lately?

Proving its never too late to start anything, at the age of 98, Toyo Shibata sold over 1.5 million copies of her poetry collection in Japan, later achieving international fame in Asia and Europe. Shown at Australia’s national 17th Japanese Film Festival a mere week after its release in Japan, “Don’t Lose Heart”, is the film inspired by Toyo’s life and her poetry. Its international premier in Sydney was also accompanied by both the visiting director Yoshihiro Fukagawa, and the main star who plays Toyo, Kaoru Yachigusa, a legendary name in Japanese cinema.

Up until the time Toyo received recognition of her work, she lived a typical, seemingly unremarkable life as a elderly member of Japan’s rapidly aging population: a widow who lives alone, with one surviving son, Kenichi (Tetsuya Takeda) , an unreliable, chronic gambler who is terminally unemployed and financially supported by his exasperated but ultimately loving wife, Shizuko (Ran Ito). Worried about the mental state of his mother, and feeling guilty about what a big loser he is, Kenichi writes poetry with her as away of spending more time together, which eventually brought out her literary talents.

Films which contain roles for older actors are rare, and as Yachigusa said during the Q&A after the movie’s screening in Sydney, good roles are even rarer still. Yachigusa has the challenge of developing Toyo as being more than just another grannie. At first Toyo seems pitiful – she is beset by the usual ills that advanced age brings, finding it difficult to move around pain-free without a walking stick. She seems a little bland, quiet and unremarkable. However when she begins to write, the film shifts into exploring the source of her inspiration, in flashbacks that regress further and further into time. “Don’t Lose Heart” is certainly aptly named, as Toyo, in her quiet way, reaches out to counsel those around her with the benefit of her experience. By the end, Toyo is revealed to be anything but ordinary. Being alive is a pretty difficult gig for anyone, and Toyo proves she’s just as tough a chick as any fictional superhero, and more inspiring than any easily digestible soundbite artificially manufactured by cynical corporations to move units.

Yachigusa is just extraordinary in her performance. Her Toyo is dignified and gentle, but with a hint of impish mischief that shows a quick and intelligent mind is alive and well – quite similar to Yachigusa herself in the interview. She gives Toyo vulnerability and frailty, but is able to convey the fighter and survivor beneath the exterior, and the resulting sense of compassion and understanding of human nature gained from having being through it all herself. Takeda plays Kenichi as a petulant short-tempered man-child, a bit over the top maybe (you have to wonder what the real Kenichi thought of his on-screen portrayal) but possessing of the same compassionate basic nature of his mother. And as Kenichi’s wife, Ito is also superb, displaying the patience of a saint in staying with him all through the years.

Be warned: this film moved Sydney audience to tears, rather loudly too, perhaps because Toyo seemed like the kind of grandmother everyone wishes they have (unfortunately Japan’s national grandmother passed away earlier this year at the age of 101). Fukagawa said that her poetry gained prominence because of their simplicity and lack of pretension and their inherent optimism and positivity, qualities that he tries to convey in his film. He can be rather sentimental at times, imparting an almost saintly, Buddha-like glow on Toyo by the end of the film, but there is a lot of respect for the source material in this film, and it shows, resulting in a tender, tribute to not just Toyo’s writings, but to the human condition itself.

Don’t Lose Heart (Kujikenaide) by Yoshihiro Fukagawa, released November 16 2013 in Japan. Starring Kaoru Yachigusa, Tetsuya Takeda, Ran Ito, Mizuho Suzuki and Yusuke Kamiji.

As Australia’s 17th Japanese Film Festival is begins its last city tour in Melbourne, the capital of the southern state of Victoria, Eden Law (Fukushima-ken ALT 2010-2011, current JETAA NSW committee member) reviews some of what is on offer. Stay tune for more reviews!

Everyone’s feeling somewhat uncomfortable now.

Okay, so what would you think if I told you that Maruyama, the main character in this film, spends most of the film trying to touch tongue to his own peen? A certain expectation will be set, wouldn’t it? Like, there wouldn’t be much else to expect from the plot except whether that lollypop gets licked. So it’s pleasantly surprising to find that it’s actually less like a string of dick jokes (unlike this review), and more of an endearingly quirky film.

Our hero with a quest, Maruyama, is a hormonal 14-year-old with a rather active imagination, frequently dreaming up imagined lives for his family and residents of his apartment complex. We’re taken through his daydreams, which range from randy fantasies filled with bouncy ladies, to colourful scenarios that get sillier and funnier as he imagines various people being either wacky fruit-themed superheroes, scissor-wielding gangsters or aliens. But Maruyama decides that he needs a hobby to distract him from such childish preoccupations, one that will bring focus and maturity – like attempting to orally do one’s own dong. However, he later befriends a dorky, uncharismatic single father, Shimoi (played with surprising ability by Tsuyoshi Kusanagi, a member of the ageless Japanese boy band SMAP), who encourages him to embrace his fantasies. Real life can be more strange than any fantasy, and a bit of strangeness is nothing to be ashamed of, but celebrated.

Maruyama’s world is undeniably ridiculous and entertaining (and sometimes sticky) as the imagination of a teen could be. And despite Maruyama’s overarching ambition to boldly try what many men have tried before (and failed, and the few that do make a career out of it), a sweet, innocent quality exists, thanks to director Kankuro Kudo’s affectionate treatment of him and all the eccentric and flawed characters that populate the neighbourhood. It’s quite an accomplishment that “Maruyama” manages to build a more substantial film on such an unlikely basis, and it results in a film that’s like a funnier combination of a Wes Andersen and Michel Gondry movie. Hiraoka Takuma, being close to the age of the character Maruyama that he plays, embodies the innocence and determined Maruyama well, shining with youthful enthusiasm, embarrassment and determination as he takes his character from zero to hero. The whole ensemble cast is perfect in their various roles, obviously having a lot of fun, from Kenji Endo’s geriatric grandfather with a surprising ability, and Maki Sakai as Maruyama’s Korean drama-obsessed mother.

It’s hard for any film to sustain the initial novelty of the first half right to the end, and “Maruyama” suffers the same problem as it gets a bit flaccid towards the end. However, the film still climaxes in a satisfactory way that, while lacking in the same vigor and energy of the start, manages to tie up all the plot threads and situations. While “Maruyama’s” length is a bit too long for comfort, overall, it charms with its humor and originality – not bad for a film that started off with auto-fellatio.

Maruyama the Middle Schooler (Chuugakusei Maruyama) by Kankuro Kudo, released in Japan April 21 2013, starring Tsuyoshi Kusanagi, Hiraoka Takuma, Kenji Endo, Yang Ik-June, Maki Sakai, Toru Nakamura, Nanami Nabemoto, Yuiko Kariya

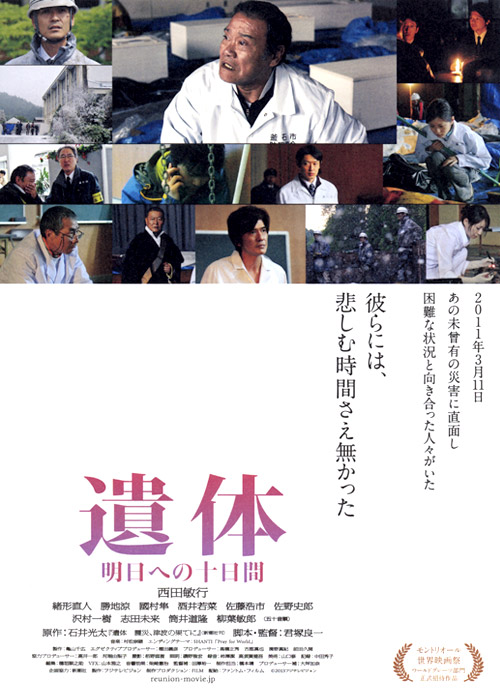

“Reunion” – Film Review from Australia’s 17th Japanese Film Festival

Australia’s 17th Japanese Film Festival is soon embarking on its last city tour in Melbourne, the capital of the southern state of Victoria, after being shown around Australia in the first ever national film festival administered by the Japan Foundation. Eden Law (Fukushima-ken ALT 2010-2011, current JETAA NSW committee member) got to see some of what’s on offer during its recent run in Sydney. This one’s for you, Melbournites! Don’t say we don’t do anything for you south of the border.

If you can’t feel anything watching this, you are probably dead inside.

It has been almost three years since the disaster that devastated the north of Japan. There have since been a handful of films on the event, on the nation and it’s people as they resolutely look forward to “revival” and reconstruction. However, few of those films, I suspect, would have dealt quite so starkly and closely on the subject of death quite like “Reunion”.

“Reunion” is a dramatization of Itai: Shinsai, Tsunami no Hate ni (遺体―震災、津波の果てに?, “The Bodies at the End of the Earthquake and Tsunami”), a reportage of the events by Kota Ishii in the days immediately following the earthquake and tsunami of March 11. A brief snapshot of the normal, mundane lives around town in the beginning, contrasts sharply the aftermath, showing how unprepared and ill-equipped the small town’s public servants were, as bodies kept coming into the temporary morgue set up in the old high school gymnasium, and distraught relatives plead for information and support. Horrified by the disorganization and haphazard treatment of the dead, Aiba (played by Toshiyuki Nishida), a retired funeral home director, volunteers to oversee the proper administration of the morgue. He shows the exhausted and numbed workers how to massage limbs stiffened by rigor mortis until they became pliant again for proper positioning, and how to counsel and deal with the grieving and traumatized people who come to identify the deceased. And slowly, people carry on with their jobs, because there is very little other choice.

This will be the most heart-breaking film you’ll ever watch this year. I’ve never cried at the movies before (if there’s anybody watching), but looks like there’s the first time for everything. While the subject matter itself is undeniably powerful and emotional, “Reunion” is actually quite simple, a recounting of the events and the personal tragedies of those who survived. Music is used sparingly in this film, the silence heightening the solemnity and noises that included the constant squelching of the mud-logged boots and the sobs of the bereaved, background sounds as described in the book. Director Ryoichi Kimizuka makes sure that the deceased is an all-pervasive presence, as the cast of characters work with them and around them, uncovering their blackened swollen faces, identifying them and saying prayers for their souls. Thanks to Aiba’s character, not only are the workers brought around to empathise with the dead, as their names and personal stories are revealed, but the audience also becomes involved. Little wonder then, that at many events where this film has been screened, audiences have been emotionally devastated.

In this film where multiple stories and tragedies play out, the cast work marvellously well together. There are very little histrionics or hysteria, just numbed helplessness, as many at first wander confusedly about before being given direction by Aiba. Performances are muted and restrained, which make the break-down moments even more heart-wrenching, for everyone has their trigger, be it the discovery of a loved one’s body while carrying out work, or the tragedy of a young child, unclaimed by any surviving relatives. There are no questions of morality, no “why did this happen to us”, soul-searching, condemnation or religious debate to be had that can be adequate. From Aiba’s point of view however, the answer is to never forget one’s humanity, which can be even more precious than food, in order to survive the unrelenting horror and sorrow of the situation. And that in the end, ultimately provides a glimmer of positivity in this film, as well as in life.

Reunion (Itai: Shinsai, Tsunami no Hate ni) by Ryoichi Kimizuka, released in Japan February 23 2013, starring Toshiyuki Nishida, Naoto Ogata, Ryo Katsuji, Jun Kunimura, Wakana Sakai, Tsuneo Aiba, Kenichi Domon, Yuta Oikawa, Yoshito Shibata, Takae Oshita, Koichi Sato, Shiro Sano, Ikki Sawamura, Mirai Shida, Michitaka Tsutsui, Michio Shimoizumi, Takeshi Yamaguchi, Nobutsugu Matsuda, Yuko Terui, Daisuke Hiraga, Toshiro Yanagiba

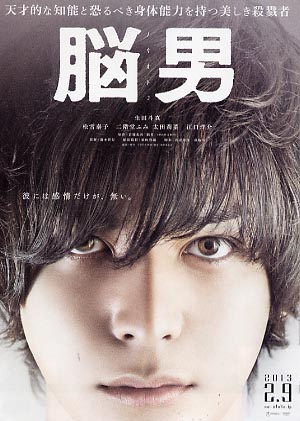

“Brain Man” – Film Review from Australia’s Japanese Film Festival

Australia’s 17th Japanese Film Festival is soon embarking on its last city tour in Melbourne, the capital of the southern state of Victoria, after being shown around Australia in the first ever national film festival administered by the Japan Foundation. Eden Law (Fukushima-ken ALT 2010-2011, current JETAA NSW committee member) got to see some of what’s on offer during its recent run in Sydney. This one’s for you, Melbournites! Don’t say we don’t do anything for you south of the border.

Doumo arigatou Mr Roboto

At times graphically brutal and sadistic, “Brain Man” moves at a brisk pace, frequently keeping the audience off-balance with unsettling scenes and stylistic ideas that are reminiscent of other films in the genre. An adaptation of the novel “No Otoko” by Urio Shudo, the novel itself won the 2000 Edogawa Rampo Award for newcomers to crime fiction. In it, a series of sadistic murders and explosions pressures the police lead by Detective Chaya (Yosuke Eguchi, who must be channelling every crusty, grouchy detective character ever to exist in film) to find the culprits responsible, and soon enough Ichiro (Toma Ikuta) is apprehended as the prime suspect. However, things are rather decidedly odd about Ichiro, who is more like a robot than a human, going like clockwork to… go, unable to feel pain or emotion. Although in peak physical condition (via an establishing shot as the camera lingers over Toma’s skinny yet hard-bodied torso, which is itself inhumanly bereft of fat), he is clearly a special psychiatric case, which is where Dr Washiya (Yasuko Matsuyuki), a brilliant psychiatrist, comes in to help with police investigation. Although like other characters in the film, she herself carries a trauma, that fuels her determination to investigate and uncover the truth about Ichiro, and ultimately the case.

This film calls for a certain suspension of disbelief – probably more than usual, with the number of implausibilities it has. This is not a film that is completely grounded in reality, even given the premise of a serial-bomber-Saw-wannabe and a man-bot. However, that’s not to say it’s done badly. Director Tomoyuki Takimoto excels at creating a tense, unsettling atmosphere, typically using lots of dark cold colours that’s grim and claustrophobic, even in the day scenes. There are unexpected shocks punctuating the film at a brisk pace, creating a sense of dangerous unpredictability for the characters. Takimoto doesn’t shy away from being graphic either, what with body parts being ripped, stabbed, shredded or sliced merrily in some form or another, in sadistically creative ways. Some of the characters and baddies are suitably over the top (especially Fumi Nikaido and Rina Ohta as Noriko and Yuria, in deliciously scenery-chewing performances), though are a little obscure in their motivation. But whatever man, they’re totes cray-cray – who can understand why they do the things they do.

But that sort of unreality element can work against it, especially when the film, in the form of Dr Washiya, seems to be exploring more serious and unexpectedly philosophical issues: can a person be rehabilitated, or their basic nature changed? In the beginning of the film, Dr Washiya advocates a new form of “narrative” therapy to habilitate hardened criminals, contrary to the accepted methods of the establishment. It’s a theme that surfaces once in a while throughout the film, although largely overwhelmed by the more exciting and visceral violence and terror. But during those moments, Matsuyuki (as the doctor) does really well in giving her character the right mix of toughness and vulnerability, and her interaction with a “cured” patient, brings a totally different kind of disturbing creepiness thanks in no small part to Shota Sometani who plays Shimura, the patient in question. But these differences seem out of place in a film that’s usually more thrills and spills, in a world where a grizzled no-nonsense detective has long hair and the living coin-operated boy somehow has access to a great hair stylist and chic clothes.

However, as mentioned, “Brain Man” is still done well and is highly enjoyable to watch, especially if you’re a fan of the thriller/crime/mystery genre. As Ichiro, Toma Ikuta’s highly restrained acting, communicating only through subtle body language and stares, is quite absorbing. And “Brain Man” manages to deliver right to the end, as a final emotional shock is revealed.

PS: Bonus points for the ending credit song: “21st Century Schizoid Man” by King Crimson!

Brain Man (No Otoko) by Tomoyuki Takimoto, released in Japan February 9 2013, starring Toma Ikuta, Yasuko Matsuyuki, Yosuke Iguchi, Fumi Nikaido and Rina Ohta.

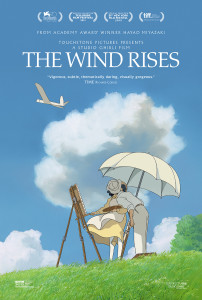

“The Wind Rises is a combination of everything that makes Studio Ghibli as we know it today. It also adds several new elements which make this film dynamic and, some say, controversial.” (Touchstone Pictures)

By Alexis Agliano Sanborn (Shimane-ken, 2009-11) for JQ magazine. Alexis is a graduate of Harvard University’s Regional Studies—East Asia (RSEA) program, and currently works as an executive assistant at Asia Society in New York City.

Written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, The Wind Rises is like no Studio Ghibli movie I have ever seen. No. Wait. It’s like every Ghibli movie I have ever seen. You want fantasy? You got it. You want airships à la Castle in the Sky or Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind? You got it. You want deliciously portrayed food? You want nostalgic scenery from bygone days of Tokyo or picturesque European towns? You got that, too. The Wind Rises is a combination of everything that makes Ghibli as we know it today. It also adds several new elements which make this film dynamic and, some say, controversial.

One of the most differentiating factors is that The Wind Rises is the only full-length feature to focus on an actual historical figure—Jiro Horikoshi, the designer of the Mitsubishi A5M, a fighter aircraft of World War II. Granted, Miyazaki used his artistic license to embellish the narrative—but he does that only to make things more beautiful and fantastical. (And that’s why we love Miyazaki, right?)

Watching The Wind Rises, you feel repeatedly—and indeed the entire plot more or less focuses on—Japan’s desperation to achieve modernity according to “Western standards.” But modernization was not a smooth road, and Miyazaki makes that message clear. Despite the beautiful veneer, the crux of this film lies in the frustration of a country and its people. Economic deflation, poverty, and limited resources repeatedly arise as roadblocks. (This may explain part of the reason for its amazing popularity in Japan. Frustrations, impatience and desperation exist within every generation.) Yet, as Jiro is reminded, even with setbacks and disappointments, one must live on and progress despite it all.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Dreams of Love, Etc.’ from ‘Monkey Business Volume 3’

“Most striking about this piece is how astute Kawakami is in capturing not only the loneliness and boredom of daily life, but the paradox of how absurd life is and how, ultimately, it’s also really no big deal.” (A Public Space)

By Sharona Moskowitz (Fukuoka-ken, 2000-01) for JQ magazine. Sharona is interested in fresh, new voices in fiction and creative nonfiction.

In the latest issue of contemporary Japanese literature anthology Monkey Business Volume 3, Japanese novelist Mieko Kawakami writes of roses, post-earthquake malaise and a friendship that never quite consummates.

We first encounter the narrator, who inexplicably calls herself Bianca, as she stands on her porch tending to her bed of roses.

By her own admission, Bianca’s days are filled with nothing—“I don’t work. I’m not pregnant. I don’t watch TV. I don’t read books. Come to think of it, I do absolutely nothing.” What she is, however, is a wife—a loaded title for a Japanese woman with its implications of duty and decorum. Yet she wants more—much more. What exactly, she isn’t quite sure.

Stuck in the doldrums of her daily existence, she thinks and rethinks the simplest decisions, her inner monologue playing out like T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” (“Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?”) What little volition she has is spent on tending to her plants, a hobby she developed after the earthquake, perhaps as an outlet for her nurturing tendencies, or, more likely, as a reminder that life was returning to normal after the shaker and its ensuing chaos.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail’

JET alum Kelly Luce’s first published collection of fiction, Three Scenarios often utilizes magic realism to tell stories that take place in Nippon. (A Strange Object)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-10) for JQ magazine. A former head of the JETAA Philadelphia Sub-Chapter, Rashaad currently studies responsible tourism management at Leeds Metropolitan University. For more on his life in the UK and enthusiasm for taiko drumming, visit his blog at www.gettingpounded.wordpress.com.

As mysterious as Japan seems to be, there are numerous occurrences in the country that leave you amazed.

Enter Kelly Luce (Kawasaki/Tokushima-ken, 2002-04). The JET Program alum’s first published collection of fiction, Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail (which is also the title of one of Luce’s stories) often utilizes magic realism to tell stories that take place in Nippon.

Three Scenarios contains ten stories and the first one, titled “Ms. Yamada’s Toaster” (which previously appeared in the anthology Tomo), tells the tale of a toaster that can predict one’s death (the toaster even predicted the death of Ms. Yamada’s husband by popping out a piece of bread three days before he suffered a heart attack). In other stories in Three Scenarios, a teenage girl disappears during karaoke and a stone is haunted by a demon.

While there may be times in Luce’s stories that Japan may seem inconsequential, the “it could only happen in Japan” moments make her stories came alive. For example, in “The Blue Demon of Ikumi,” a foreigner woman who was considered a demon because a child died under her care is set to be executed (she eventually escapes). In “Wisher,” people make seasonal wishes at a fountain’s stone steps, such as students and parents praying before entrance exams in autumn and during summer for travel. And in the above-mentioned “Ms. Yamada’s Toaster,” some villagers wish to make the toaster a deity.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Gadget Girl: The Art of Being Invisible’

“As Gadget Girl is geared toward young adults (or more specifically, teenage girls), it is an easy read. But you get the sense that because of its diverse set of characters, it would make a good TV drama.” (GemmaMedia)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-2010) for JQ magazine. Rashaad worked at four elementary schools and three junior high schools on JET, and taught a weekly conversion class in Haguro (his village) to adults. He completed the Tokyo Marathon in 2010, and was also a member of a taiko group in Haguro.

Sometimes, we’re just trying to find out where we belong.

That’s certainly the case with Aiko Cassidy, the teenage protagonist of JET Program alum Suzanne Kamata (Tokushima-ken, 1988-1990)’s latest novel, Gadget Girl: The Art of Being Invisible. The 15-year-old daughter of a renowned sculptor, Aiko wants to develop her own identity, instead of being known as Laina Cassidy’s muse and suffering from a disability (cerebral palsy). Aiko has been secretly working on manga titled Gadget Girl, and she dreams of becoming a world famous manga artist—which would enable her to visit her father in Japan.

But instead of heading to the Land of the Rising Sun, Aiko is off to France for several days, as Laina has won the grand prize at the prestigious Prix de Paris. Although she’s still receiving the “Laina Cassidy’s muse” treatment, the City of Light does open up a new world for Aiko. For one, she develops a crush on a waiter named Hervé at the café she frequents. Aiko is also introduced to the spot where he parents met but more importantly, she learns the reason why her father is absent from her life.

Inspired by the movie The Song of Bernadette, Aiko and Laina head to Lourdes, where Aiko dreams of being cured. Instead, she hears a woman whisper “Forgive,” and Aiko uses that as a call to repair broken relationships in her life.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘The Accidental Office Lady: An American Woman in Corporate Japan’

“If you are going to Japan soon, live there now, or have lived there already, this book is a survivor’s guide and tool for reflection and growth. It can help the reader better understand what to do, and what not to do.” (Tuttle)

By Lana Kitcher (Yamanashi-ken, 2010-12) for JQ magazine. Lana is the business development associate for Bridges to Japan and enjoys working as a freelance writer for a number of online publications. To read more about Lana’s adventures in Japan, visit her blog at Kitcher’s Café.

Laura Kriska’s experience as recounted in The Accidental Office Lady parallels in many ways what we as JET participants go through when we temporarily leave our lives and routines at home to pursue the “exotic” and uncertain terrain of a new culture.

Based on Kriska’s background and education, she was offered a two-year position at Honda Motor Company headquarters in Tokyo, being the first American woman to do so. She arrived in Japan equipped with her new business attire and a mind full of expectations and dreams about how the next two years of her life in Tokyo would unfold. She was soon instructed to join the secretariat—coordinating schedules and serving tea to managers in her new, polyester uniform.

Through the course of the book we get to see Kriska transform from a newly minted grad into a successful member of Japanese society. She starts out frustrated by her new environment and deeply disappointed that her job is not all that she hoped it would be. As the book progresses, you start to see that she is losing her childish tendencies to fight back, and eloquently navigating the culture with words and mannerisms instead of outbursts and small rebellions. She takes on more responsibility and in the end is able to create lasting change at Honda with a new employee manual in English and the elimination of the mandatory uniform rule.

JQ Magazine: DVD Review – ‘From Up on Poppy Hill’

“Studio Ghibli films are known for their fantastical animation and surrealistic landscapes. However, Poppy Hill lacks one other crucial element common to Ghibili films: an emotional depth of feeling.” (GKIDS)

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama-shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle is entering a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University (MIA 2013) and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City-based soccer team.

From Up on Poppy Hill is the latest film to be released from Japan’s famed Studio Ghibli. Unlike its more prominent titles, this one is not directed by studio founder Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle) but rather by his son Goro Miyazaki. The father did, however, co-write the script (with Keiko Niwa), which was adapted from a manga published in the 1980s. Goro’s first film, Tales from Earthsea, was a commercial hit but received a very negative reception, even receiving “Worst Director” and “Worst Picture” designations from the Bunshun Raspberry Awards, given annually to the worst in cinema by the Bungeishunju Publishing Company. From Up on Poppy Hill received a much better reception (although many reviews were mixed) and became the highest grossing Japanese film of 2011 and won the 2012 Japan Academy Prize for Animation of the Year.

The story takes place in Yokohama in 1963, a pivotal point in Japan’s history as the country was preparing for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. The nation was on the economic upswing and the Olympics were meant to showcase the “new” Japan as it pushed its postwar ruin firmly into the past. Within this context, Poppy Hill tells two stories, both of which deal with historical consciousness. The first concerns a high school student named Umi, who lives and works in her family’s boarding house. Her father was lost at sea during the Korean War and Umi flies nautical flags daily from her house in order to wish peace upon all sailors. The second story concerns a clubhouse (named the Latin Quarter), which has been slated for demolition to make way for an Olympics-related building. The building is adjacent to Umi’s high school and she meets Shun, the leader of the clubhouse, who also happens to have been decoding her nautical flags each morning. Umi leads an effort to clean up the clubhouse and soon starts to fall in love with Shun.

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty’s Trek Across the Pacific’

“Pink Globalization is a culmination of over ten years of Yano’s fieldwork and research on the international ubiquity of Hello Kitty as an example of Japan’s actions as a tastemaker in global kawaii.” (Duke University Press)

By Jessica Sattell (Fukuoka-ken, 2007-08) for JQ magazine. Jessica is a freelance writer and a graduate student in arts journalism. She readily admits that while she is an avid Hello Kitty fan, she is always going to like Chococat more.

For many, young and old, female and male, Hello Kitty (or Kitty-chan, as her diehard fans lovingly call her) has been a lifelong friend. As I toted around my review copy of the new Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty’s Trek Across the Pacific—to my part-time job, to coffee shops, on a recent trip—strangers cooed over the cover’s soft pink color scheme and photograph of one of artist Tom Sachs’s renditions of the famous feline. Kitty led the way into my very first experiences with Japan, and her ever-presence has enriched my life in ways that I didn’t fully understand until diving in to Christine R. Yano’s research.

The wide-eyed little cat has been Japan’s acting ambassador for decades, and her global travels had (and continue to have) profound impacts on generations of consumers and culture shapers. Pink Globalization is a culmination of over ten years of Yano’s fieldwork and research on the international ubiquity of Hello Kitty as an example of Japan’s actions as a tastemaker in global kawaii.

Yano, who is Professor and Chair of Anthropology at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, explains that Kitty’s rise, development and continuing presence as perpetuated by both parent company Sanrio and an ever-growing fandom provides a rich text from which to examine a multitude of contemporary issues. Yano coins the term “pink globalization” here to refer to the spread of “cute” goods and images from Japan to other parts of the world, and it connects the actions of global capitalism with Japan’s “coolness” in its soft cultural products.

JQ Magazine: Film Review – ‘Cutie and the Boxer’ Pairs Sparring Partners in Life, Art

“Director Zachary Heinzerling spent five years with the Shinoharas in the making of his movie, and it has been recognized with critical praise and honors including the U.S. Documentary Directing Award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.” (RADiUS-TWC)

By Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken CIR, 2000-03) for JQ magazine. Stacy is a professional Japanese writer/interpreter/translator. She starts her day by watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese, and shares some of the interesting tidbits and trends together with her own observations in the periodic series WITLife.

Director Zachary Heinzerling’s debut documentary is the captivating Cutie and the Boxer, which follows two New York-based Japanese artists who have been married for over 40 years. It stars Ushio and Noriko Shinohara, a couple separated in age by two decades who have a truly unique union. They alternately bicker and support each other, but you get the sense that their respective existences are necessary for the other to survive. As wife Noriko puts it, “We are like two flowers in one pot,” meaning that when things are going well they are essential for each other’s flourishing, but when things are not they are fighting over limited space and nourishment.

Ushio (a.k.a. Gyu-chan) is an artist who was active in the avant-garde art movement, and is known for his boxing paintings and motorcycle sculptures. He achieved great fame in Tokyo before moving to New York to test his skills in the States. He was 40 at the time he met Noriko, who was 19 and had come to New York to study art. Things happened quickly between them, and soon they were married with a son, Alex. Noriko put aside her artistic aspirations to help Ushio in his career and raise Alex, thus curbing the potential for her own success.

Meanwhile, Ushio was floundering in building a name for himself as an artist in his new country. Despite the fact that he had become a father, he didn’t want to move beyond his old ways of drinking with friends and discussing philosophies regarding art. One of the most poignant and candid scenes in the film is when Ushio becomes quite drunk at one of these gatherings and emotionally describes both the pain and sublime pleasure he receives from creating art, saying that he would rather die than do anything else with this life. It is one of the film’s truly heartbreaking and inspiring moments.