JQ Magazine: Film Review — ‘The Tale of the Princess Kaguya’

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama-shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle has completed a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association of New York since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City-based soccer team.

When one hears the name “Studio Ghibli,” the director Hayao Miyazaki immediately comes to mind. Starting with Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind in 1984, Miyazaki has continually delivered hit after hit for the past 30 years, making him the most successful contemporary Japanese filmmaker (animated or otherwise). Moviegoers can be forgiven for not recognizing the name of Miyazaki’s partner and Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata, who tends to operate behind the spotlight. But Takahata is an accomplished animator and filmmaker in his own right.

In the West, he is best known for the extraordinary Grave of the Fireflies (1988), a powerful anti-war epic about the firebombing of Kobe during the Second World War. Roger Ebert considered Fireflies one of the best war films ever made, and it certainly ranks among Studio Ghibli’s greatest efforts, elevating the standards of anime depicting serious subject matter. Takahata’s other films were successful in Japan but received limited distribution in the West—notably the ecologically minded Pom Poko (1994) and the comic strip-inspired comedy My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999). From this selection of titles, it is clear that Takahata can work in a variety of genres with different animation styles. Unlike Miyazaki, he delegates much of the animation work and does not have an immediately recognizable aesthetic.

Last year, both Miyazaki and Takahata announced their retirements. For his swan song, Miyazaki released the controversial The Wind Rises (read JQ’s review here), which managed to receive criticism from both the political left and the right in its treatment of the war. Takahata decided to end his career with a project that he conceived and abandoned 55 years ago: A feature film version of the tenth century folktale The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. Both films were to be released simultaneously in a show of solidarity, but production delays resulted in a later distribution for Takahata’s film. The film became a big hit domestically, and is now receiving its U.S. release under the title The Tale of the Princess Kaguya in both subtitled and dubbed versions.

Justin’s Japan: Nippon in New York — Studio Ghibli, New York Comic Con, X Japan, Hatsune Miku

Catch the New York premiere of Studio Ghibli’s “The Tale of Princess Kaguya” at IFC Center Oct. 3. (GKIDS)

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his Japanese culture page here for related stories.

The Japan-centric events of the month ahead promise to be as rich and full as autumn itself—brisk and colorful, with a dash of unpredictability.

This month’s highlights include:

Friday, October 3, 6:30 p.m.

IFC Center, 323 Avenue of the Americas

$14

New York premiere! Legendary Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata (Grave of the Fireflies, Pom Poko) revisits an ancient Japanese folktale in this gorgeous, hand- drawn masterwork decades in the making. Found inside a shining stalk of bamboo by an old bamboo cutter (James Caan) and his wife (Mary Steenburgen), a tiny girl grows into an exquisite young lady (Chloë Grace Moretz). The beautiful princess enthralls all who encounter her—but ultimately she must confront her fate. The film will have a “sneak preview” screening in Japanese at IFC Center on Thursday, Oct. 16 prior to its regular run Oct. 17. Click here for additional showtimes.

Sunday, Oct. 5, 4:00 p.m.

Best Buy Theater, 1515 Broadway

$42

The 10-member Morning Musume ’14, also known as Momusu, are one of the most successful Japanese all-girl idol groups, produced by the famous rock writer-producer Tsunku. Their music style is poppy and upbeat, matched only by their elaborately choreographed dance performances. Their story began in 1997 after a TV audition and they made their major debut in 1998.The following year, their single “Love Machine” was their first to sell over one million units. Morning Musume ’14 have already performed in China, Taiwan, South Korea, France and the USA (Los Angeles), and are poised to make their New York stage debut.

Sunday, Oct. 5, 7:00 p.m.

Peter Jay Sharp Theatre at Symphony Space, 2537 Broadway

$40/$30 members, students and seniors/$22 children

Experience the thunderous rhyhms of the ancestral Japanese taiko drums and the magical sounds of the bamboo flutes, as Taikoza returns with richly authentic performances and colorful Japanese dances. The international touring taiko group, led by Swiss-born director Marco Lienhard, will present new compositions as well as traditional pieces in this unique concert featuring special guest from Japan Ichiro Jishoya, who was recently featured in the documentary film Drum Out the Drum of Happiness – Inclusion. This concert will celebrate the 150 anniversary of the diplomatic relationship between Switzerland and Japan.

For the complete story, click here.

Justin’s Japan: Interview with James Rolfe of Cinemassacre on ‘Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie’

James Rolfe, left, on the Angry Video Game Nerd movie with co-writer/co-director Kevin Finn: “To me, it’s the ultimate fan-film. It’s made by fans, for fans. It means dreams can come true, with a lot of hard work and personal sacrifice.” (Justin Tedaldi)

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his Japanese culture page here for related stories.

An Internet sensation that debuted as the Angry Video Game Nerd ten years ago, filmmaker James Rolfe has taken millions of YouTube visitors back to the past with his hotheaded, foulmouthed alter ego, who gleefully tears down some of the most notorious titles and accessories (the Power Glove, anyone?) from the golden age of retrogaming. (If you’ve ever thrown a controller across the room, you’ll understand.)

As the creative linchpin of his website and production company Cinemassacre, the AVGN legend culminates with this year’s release of Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie, a feature-length, years-in-the-making collaborative effort between Rolfe and co-writer/co-director Kevin Finn. A satisfyingly silly sci-fi/adventure hybrid in the Troma tradition, the film enjoyed a sold out 16-city North American screening tour earlier this summer, and makes its Vimeo on Demand debut today (Sept. 2), with a DVD/Blu-ray release planned for the holiday season.

In this exclusive, wide-ranging interview, I spoke with Rolfe about everything from the film’s New York premiere last month, the Nerd Renaissance we’re currently living in, and the most “Japanese” (i.e., insane) game he’s ever played.

It feels like we’re living in some kind of Nerd Renaissance—even “Weird Al” Yankovic’s last album went to number one. How do you feel about all this?

Nerds were big in the ’80s. It’s all coming back now. I feel there’s a much broader definition of “nerd” now, and it’s something to be proud of.

What are your thoughts on the live appearances you’ve had promoting the film so far? Which moments have been the most memorable?

Since July 21, we’ve been touring this movie around, city by city. It’s been amazing. The energy from the crowd is fantastic! There’s nothing like watching the movie with live reactions. The best moment is during the opening credits. Everyone cheers. Sometimes they clap along with the music. You can really feel the hype building up to the AVGN title screen. Then it explodes, and everyone goes nuts.

What can you share about the back-to-back screenings held for the New York premiere?

It was a rowdy crowd. Especially the second screening. I loved it, though it was exhausting. Under normal circumstances, I would be sick of looking at this movie, but the fans make it exciting every time. It never gets old.

Mount Fuji and Godzilla movies play a prominent role in the film. If you were to ever visit Japan, what would you most want to see and do there?

I’ve always wanted to go. There isn’t one thing in particular. I’d just like to see all around the major cities like Tokyo. Just normal tourist things.

What are some of your favorite moments of “Japaneseness” in video games that you’d like to give a shout-out to?

Hmmm. Not sure. Probably Ninja Baseball Bat Man! That game is insane.

For the complete story, click here.

Justin’s Japan: Nippon in New York – ‘Dragon Ball Z,’ ‘Naruto,’ ‘Angry Video Game Nerd’ premieres

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his Japanese culture page here for related stories.

In the dog days of summer, it’s best to escape the heat in a place that’s cozy and cool. For those into Japanese cultural events, this month offers a diverse selection of film premieres and live music—all in the comfort of indoor air conditioning.

Aug. 5, 9 and 11

Village East Cinema, 181-189 Second Avenue

$14

Stunning animation and epic new villains highlight the first new Dragon Ball Z feature film in seventeen years! After the defeat of Majin Buu, a new power awakens and threatens humanity. Beerus, an ancient and powerful God of Destruction, searches for Goku after hearing rumors of the Saiyan warrior who defeated Frieza. Realizing the threat Beerus poses to their home planet, the Z-fighters must find a way to stop him before it’s too late. An original work from Dragon Ball series creator Akira Toriyama, Battle of Gods is an exciting new adventure for DBZ fans everywhere. Presented in English. Additional screenings will be held on Aug. 5 at AMC Empire 25 and Regal Union Square Stadium 14. Click here for tickets.

Friday, Aug. 8, 3:30 p.m. and 7:30 p.m.

Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie

Symphony Space, 2537 Broadway

$20

NYC premiere! Based on the hit web series of the same name, the newly released adventure-comedy, Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie, follows a disgruntled gamer who must overcome his fear of the worst video game of all time in order to save his fans. Hilarity ensues as a simple road trip becomes an extravagant pursuit of the unexpected. Starring James Rolfe. Written and Directed by James Rolfe and Kevin Finn. A Q&A follows the screening with James Rolfe and Special Guests.

James Rolfe and Kevin Finn’s debut feature film, Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie, follows a disgruntled gamer (Rolfe) who must overcome his fear of the worst video game of all time in order to save his fans. Desperate to disprove a video game urban legend, hilarity ensues as a simple road trip becomes an extravagant pursuit of the unexpected – and the unexpected ultimately proves that what’s in front of you, isn’t always what it appears to be. Blending elements of comedy, science fiction, and horror, Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie, is an existential journey which, in the end, discovers truth can be found in the most unlikely of places – and one’s greatest weakness is not the hate one has for a game, but the devotion one has in the face of adversity.

Friday, Aug. 8, 6:00 p.m.

Peace Concert “Global Harmony” with Shinji Harada

West Park Presbyterian Church, 165 West 86th Street

$15 suggested donation

Shinji Harada is one of Japan’s most famous recording artists. He has released more than 70 singles in Japan, three of which once hit the top 20 Oricon chart simultaneously. Born in Hiroshima, Shinji was recently recognized by his home town as a Hiroshima Peace Culture Ambassador.

Shinji became a musical sensation in Japan when he released his debut single Teens’ Blues in 1977 when he was just 18 years old. He released two more singles, Candy in November and Shadow Boxer in December the same year. All three singles ranked in the Top 20 Oricon chart simultaneously, which had never happened before in Japanese music history. Through his music Shinji actively works to spread his brief in “Yamato,” the spirit of sharing kindness and loving one another. He will be joined by percussionist Mataro Misawa and bassist Wornell Jones.

Misawa is a member of Masaharu Fukuyama’s band which recently completed the “Human” tour attended by about half a million people in Japan, Taiwan and Hong Kong. ‘Human”, the album, topped the Oricon rock album chart at #1 after it’s release this spring. Mataro has also performed with many other leading Japanese musicians and groups including Southern All Stars and Masashi Sada. Jones, who is based in Tokyo, has performed with Sly and the Family Stone, Koko Taylor, as well as Chage and Aska, Hiromi Go and many other well-known Jazz and popular musicians in the US and Japan.

This is a rare chance to see some of Japan’s most famous musicians perform in NY! (Your donation will support the annual NY Hiroshima-Nagasaki peace memorial gathering.) For more information, call 646-797-7982 or email: tknakagaki[at]gmail.com.

For the complete story, click here.

Let’s Talk Japan is a monthly, interview format podcast covering a wide range of Japan-related topics. Host Nick Harling (Mie-ken, 2001-03) lived in Japan from 2001 until 2005, including two great years as a JET Program participant in Mie-Ken. He practices law in Washington, D.C., and lives with his wife who patiently listens to him talk about Japan . . . a lot.

This episode is a special JET Talks Edition of the Let’s Talk Japan Podcast featuring a panel discussion with the producers of “Kokoyakyu,” a documentary about high school baseball in Japan and the quest to qualify for the national summer baseball tournament at historic Koshien Stadium. High school baseball in Japan is a national obsession, and the Koshien summer tournament is a wonderful event through which to gain insight into Japanese society.

The 96th National Summer Baseball Tournament will be played at Koshien Stadium beginning Saturday, August 9th, and will end with the championship game on Saturday, August 23 at 1pm (JST). Here is a list on this year’s teams and a schedule of the games.

“JET Talks” is a speaker series organized by the JET Program Alumni Association of Washington, DC (“JETAADC”). JET Talks is loosely modeled after the TED Talks concept and features dynamic and interesting speakers with the goal of inspiring innovative ideas and conversations on Japan-related themes.

If you have not already done so, be sure to follow the podcast on Twitter @letstalkjapan and leave a positive rating/review in iTunes.

Justin’s Japan: ‘Dragon Ball Z,’ ‘Naruto’ Come to the Big Screen

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Shukan NY Seikatsu. Visit his Examiner.com Japanese culture page here for related stories.

This August will be a hot month for anime fans, as the latest feature length entries for two of the world’s most popular series debut at Village East Cinema.

First up (Aug. 5 and 9) is “Dragon Ball Z: Battle of Gods,” the 18th animated feature of author Akira Toriyama’s massively popular martial arts adventure series “Dragon Ball,” which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. The plot focuses on the dessert-loving God of Destruction Beerus, who awakes from a decades-long slumber to challenge Goku, the strongest fighter in the universe.

“‘Dragon Ball Z’ has been a gateway for me personally. Growing up watching Toonami in the ’90s, the series influenced me as a kid to become obsessed with Japanese animation,” said Maj Mack, founder and CEO of GoBoiano, a fast-growing anime startup with over 300,000 social media followers worldwide.

Another long-running series (fifteen years and counting), “Naruto,” premieres Aug. 31-Sept. 1 with its ninth feature film, “Road to Ninja: Naruto the Movie.” Set in an alternate timeline in which its characters have different origin stories and personalities, and featuring the theme song “Sore de wa, Mata Ashita” by the J-rock band Asian Kung-Fu Generation, “Road to Ninja” became the highest grossing “Naruto” movie to date within two months of its release in Japan.

For tickets, visit www.fandango.com.

WIT Life #272: Japan Cuts

WIT Life is a periodic series written by professional Writer/Interpreter/Translator Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken CIR, 2000-03). She starts her day by watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese, and here she shares some of the interesting tidbits and trends along with her own observations.

This weekend wrapped up Japan Society’s annual film festival Japan Cuts, and all of the films that I caught out of the 28 presented this year were wonderful. I particularly enjoyed the opening film on the first Friday of the festival, The Snow White Murder Case (白ゆき姫殺人事件). This movie made its U.S. premiere, and told the story of the murder of a beautiful young office worker. The prime suspect is her plain co-worker who has disappeared following the murder, and in the online world the case is made for her guilt before the official investigation takes place. As interviews are carried out with others at the company and the truth is gradually revealed, viewers come to realize how culpable we are in automatically convicting suspects based on hearsay and popular opinion. This film skillfully highlights just how pernicious social media can be in stringing people up before they have the opportunity to defend themselves. Although this sounds like a dark story, it also has comic moments that serve to lighten the mood.

Two kid-centered films that I liked more than I expected were Maruyama, the Middle Schooler (中学生円山) and Hello! Junichi (ハロー!純一), both of which use dance and humor to great effect. The former focuses on a 14-year old in the height of puberty who uses his active imagination to Read More

JET Talks Film Screening – “Kokoyakyu High School Baseball” Documentary and Q&A Panel

JETAA DC is proud to present the launch of JET Talks– a speaker series modeled after TED Talks that will feature dynamic and interesting individuals to inspire innovative ideas and conversation on Japan within the DC community.

Upcoming Events: Kokoyakyu Documentary and Q&A – Tuesday, July 22

Play Ball! On July 22, please join JETAADC at the Japan Information and Culture Center (1150 18th St NW #100, Washington, DC 20036) as it presents its first “JET Talk” of the 2014-2015 season: a screening of the award winning documentary Kokoyakyu: High School Baseball, followed by a discussion with two of the film’s producers.

Kokoyakyu is the first English-language film to examine high school baseball in Japan, in particular, the annual summer high school baseball tournament. The film follows one team as it seeks to play in the prestigious tournament, and along the way demonstrates why high school baseball has become a national rite of passage for many of Japan’s youth.

Following the film, Nick Harling (Mie-ken, 2001-03), JET Talks Co-Chair and creator of the Let’s Talk Japan Podcast, will lead a discussion with Kokoyakyu’s Producers Alex Shear and Takayo Nagasawa as they discuss the making of the film and the differences between the U.S. and Japan when it comes to the “National Pastime.”

Click here to register for Kokoyakyu.

Light refreshments will be served. Identification will be required to consume alcoholic beverages. Admission is free, but you must preregister.

If you have an interesting and dynamic speaker you’d like to hear speak on anything related to Japan, email us at jet.talks@jetaadc.org.

JQ Magazine: Film Review – JAPAN CUTS 2014 at Japan Society

Ken Watanabe (right), stars in Unforgiven, premiering July 15 at Japan Society in New York as part of their annual JAPAN CUTS film festival. (© 2013 Warner Entertainment Japan Inc.)

By Lyle Sylvander (Yokohama-shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Lyle has completed a master’s program at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and has been writing for the JET Alumni Association of New York since 2004. He is also the goalkeeper for FC Japan, a New York City-based soccer team.

This year’s JAPAN CUTS—North America’s biggest festival of new Japanese film—kicks off July 10-20 at New York’s Japan Society, continuing its tradition of showcasing the latest films from Japan along with some special guest stars and filmmakers. This year’s highlights include Japan’s blockbuster The Eternal Zero, The Great Passage (Japan’s submission for the Academy Award last year) and the post-3/11 documentary The Horses of Fukushima. Below are three of the 28 films in this year’s lineup that were made available to JQ at press time.

Eiji Uchida’s Greatful Dead marks the latest entry in the “dark and twisted” Japanese genre. The sordid story follows Nami (Kumi Takiuchi) as she follows “solitarians” (old and psychotic loners) around Tokyo and snaps selfies with them when they die. She enters into a morbid friendship with one particular “solitarian” (Takashi Sasano) and the rest of the film explores the darker side of humanity and mental illness in modern-day Japan. Uchida also seems to be making a statement about those most marginalized in modern Japan—the young and the elderly. Japan’s youth have a staggeringly large unemployment rate while the aging demographic makes for a perilously underfunded social security system.

Also using horror conventions for social satire is Miss Zombie, taking place in a futuristic Japan where zombies can be domesticated as servants and pets. Directed by Hiroyuki Tanaka (here using the pseudonym “Sabu”), Miss Zombie follows Shara, a mail order zombie whose owner, Dr. Teramoto, feeds her rotten vegetables in exchange for domestic labor. The film takes a darker turn as she is raped by two handymen—an event that sexually arouses Dr. Teramoto. Soon, Shara’s services are no longer limited to domestic chores. Even Dr. Teramoto’s wife finds her services useful after their son drowns. Overall, Sabu brings a fresh and interesting approach to the zombie film—a far cry from the works of George A. Romero and the countless imitators he inspired.

Justin’s Japan: Nippon in New York — Kabuki at Lincoln Center, JAPAN CUTS, NY Mets, DJ Krush

Neko Samurai ~Samurai ♥ Cat~ makes its international premiere as part of Japan Society’s annual JAPAN CUTS film festival July 19 with a live appearance by star Kazuki Kitamura. (© 2014 NEKO SAMURAI PRODUCTION COMMITTEE)

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his Japanese culture page here for related stories.

After you’ve seen the outdoor fireworks, enjoy some summer events in the cool indoors, whether it’s witnessing the return of one of the world’s most distinguished kabuki companies returning to New York after seven years, catching one of 20 films in Japan Society’s annual festival, or waiting for the bass to drop at a live performance from a legendary DJ.

July 7-12

Rose Theater, 10 Columbus Circle

$45-$190

The Heisei Nakamura-za company, which made its North American debut in a critically acclaimed and sold-out run during Lincoln Center Festival 2004, was founded by the illustrious Kanzaburo XVIII, the late patriarch of the Nakamura family—a veritable kabuki dynasty in Japan with an unbroken line of actors and innovators reaching back to the 17th century. For its Lincoln Center Festival engagement, the company has revived a rarely performed 19th-century ghost story, Kaidan Chibusa no Enoki (The Ghost Tale of the Wet Nurse Tree), about the murder of an artist by a handsome samurai who desires the artist’s wife. Running the emotional gamut from drama to uproarious slapstick comedy, and culminating in a thrilling fight-to-the-death beneath a waterfall, this is kabuki theater at its most engaging. Performed in Japanese with English synopsis via a headset.

July 10-20

Japan Society, 333 East 47th Street

$10-$20

North America’s biggest festival of new Japanese film returns for its eighth year, serving up a thrilling cross section of Japan’s diverse film cultures to New York audiences! Screening 27 features across 10 days, including co-presentations with the 13th New York Asian Film Festival, JAPAN CUTS premieres the best of recent action epics, genre oddities, touching dramas, warped comedies and cutting-edge arthouse cinema made in and around Japan. Plus, meet special guest stars and filmmakers during exclusive post-screening Q&As and raucous parties in Japan Society’s theater and atrium!

Friday, July 11, 5:30 p.m.

New York Mets Japanese Heritage Night 2014

Citi Field, 123-01 Roosevelt Avenue

Special seating $35-$72

For the fifth annual Japanese Heritage Night at Citi Field, the Mets take on the Miami Marlins for this special event. The pre-show kicks off at Mets Plaza outside with an explosive taiko set from New York’s own Soh Daiko, followed by the Mets Spirit Awards inside the stadium given to honored members of the New York Japanese and Japanese American community. Prior to the first pitch at 7:00 p.m., the Japanese Men’s Choir will perform our national anthem. A portion of the proceeds from each ticket bought will go to Japanese community charities through the Japanese American Association of New York. Be sure to look for fun Japanese activities and games throughout the evening at the special tables on the main concourse behind the giant video screen. Price of ticket includes a free T-shirt!

For the complete story, click here.

WIT Life #271: New York Japan Cinefest at Asia Society

WIT Life is a periodic series written by professional Writer/Interpreter/Translator Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken CIR, 2000-03). She starts her day by watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese, and here she shares some of the interesting tidbits and trends along with her own observations.

Last week I went to the 3rd annual New York Japan CineFest held at Asia Society. It featured six short films ranging in length from 4-30 minutes, many of which had already received awards at other film festivals. I attended with fellow JET alums, so it was fun to dissect the films together and relate them to our respective Japan adventures. The event opened with The Misadventures of Incredible Dr. Wonderfoot, and directors Grier Dill and Brett Glass were on hand to offer an introduction.

In addition, two of the movie’s stars, Tsukasa Kondo and Tadashi Mitsui, also shared their experiences of making the film. The former is actually one of the creators and stars of the web series Second Avenue, which follows two 20-something Japanese roommates in Brooklyn, an aspiring actress and a Japanese gay law student (played by Kondo). The first season of six episodes (mostly in Japanese with subtitles) are really entertaining, especially for viewers who understand Kansai-ben .

.

It was fun to watch the quirky podiatrist Dr. Wonderfoot, but my personal favorite out of all the flicks (and audience award recipient) was one of the concluding films, Little Kyota Neon Hood (I also liked the final film Lil Tokyo Reporter that was based on the true story of L.A. Japanese-American community leader Sei Fujii). This film takes place in Tohoku and features 10-year old Kyota who is suffering from Read More

Justin’s Japan: ‘Ghost in the Shell,’ Kishi Bashi, Luna Haruna at AnimeNEXT

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his Japanese culture page here for related stories.

After an unusually chilly spring, it’s finally starting to feel like summer. Enjoy some seasonal events this month that celebrate the best of both fine art and pop art.

This month’s highlights include:

Wednesday, May 28, 10:00 p.m.

The Bowery Electric, 327 Bowery

$5

An all-female quartet that delivers riff-heavy, post-punk anthems, Each of the Hard Nips came to live in New York at different times, from different parts of Japan. And, as conspired by the ever-dexterous hand of fate, they were to cross paths and become fast friends. They quickly formed a cult-like bond whose rituals all included drinking a lot of alcohol and uncontrollably running their mouths. The wine flowed like Kool-Aid and, somehow, they found themselves buying into the delusion that they were capable of forming a kick-ass rock band. Witness the next chapter in their story, with support from Shakes and the Johnnys.

Thursday, May 29, 7:30 p.m.

Ghost in the Shell: Arise – Borders: 1 & 2

AMC Loews Village 7, 66 Third Avenue

$10

In the first two parts of this highly anticipated prequel series of the anime sensation Ghost in the Shell, it’s the year after the fourth World War and cyborg/hacker Motoko Kusanagi finds herself wrapped up in the investigation of a devastating bombing. But she’s not the only one looking for answers—as she delves deeper into the mystery of who is behind the attack, a specialized team unlike any before begins to take shape.

June 6-8

Garden State Convention Center, 50 Atrium Drive, Somerset, NJ

$45-$60

The largest independently organized anime convention in the New York/New Jersey metropolitan area. AnimeNEXT features Japanese creators of anime and manga, voice actors, musical acts, artists, vendors and exhibits, events, panels, workshops, and gaming. This year’s musical guest is Tokyo’s Luna Haruna, who made her major debut in 2012 with the song “Soraha Takaku Kazeha Utau,” the ending theme song for the second season of anime series Fate/Zero. Her latest single, “Snowdrop,” was featured as the ending theme song the second season of Monogatari. Don’t miss her first-ever performance on the East Coast!

For the complete story, click here.

WIT Life #270: Godzilla!

WIT Life is a periodic series written by professional Writer/Interpreter/Translator Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken CIR, 2000-03). She starts her day by watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese, and here she shares some of the interesting tidbits and trends along with her own observations.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the first Godzilla movie, and last week the newest version was released. The cast features familiar names like (a wooly-haired and wild-eyed) Bryan Cranston, Juliette Binoche and Ken Watanabe. It has our favorite kaiju (monster) taking on a pair of MUTOs (Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organisms), the new kaiju on the block. They are ancient parasites that come from the same era and ecosystem as Godzilla, and feed off of radiation like him. In addition to destroying American cities, the male and female MUTO terrorizing the U.S. are looking to mate.

Cranston and Binoche play an engineer couple who lived in Japan with their young son in 1999, working together at the Janjira nuclear plant where something went wrong. She perished during this accident, and the movie is set in the present day when he is determined to find out what exactly happened, as he doesn’t believe that it was a natural disaster as is being claimed. Watanabe’s character is the moral compass of the movie, a scientist who knows all about Godzilla and his kind. He adds Read More

Cranston and Binoche play an engineer couple who lived in Japan with their young son in 1999, working together at the Janjira nuclear plant where something went wrong. She perished during this accident, and the movie is set in the present day when he is determined to find out what exactly happened, as he doesn’t believe that it was a natural disaster as is being claimed. Watanabe’s character is the moral compass of the movie, a scientist who knows all about Godzilla and his kind. He adds Read More

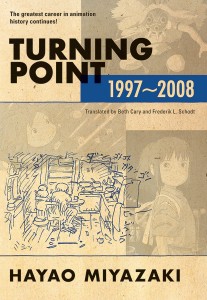

“With wit and humor, Miyazaki offers insight from his long career with every turn of the page. Like an unforgettable sunset or the first time a cooking experiment came out well, he discusses experiences that leave you unexpectedly changed.” (VIZ Media)

By Alexis Agliano Sanborn (Shimane-ken, 2009-11) for JQ magazine. Alexis is a graduate of Harvard University’s Regional Studies—East Asia (RSEA) program, and currently works as an executive assistant at Asia Society in New York City.

I consider myself an aficionado of director and animator Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli. Having seen his work countless times, visited the museum in Tokyo and done a fair amount of supplemental reading, I figured Turning Point—a collection of Miyazaki interviews and articles spanning 1997 through 2008 and newly translated by Beth Cary and Frederik L. Schodt—would probably be a rehash of the similar. I presumed it would be a book for Japan or anime specialists. On the back cover there’s even a quote from the L.A. Times: “Essential reading for anyone interested in Japanese or Western animation.” However, this statement is entirely too narrow and ultimately misleading.

In fact, the book (which is a sequel to Starting Point: 1979-1996, also translated by Cary and Schodt and now available in paperback) is less about animation and Japan than it is the human condition and those existential questions that keep you awake at night. Miyazaki, at one moment reserved and the other candid, plunges fearlessly into complex, introspective and intellectual issues about human’s relationship with education, child-rearing, philosophy, history, art, environmentalism and war (to name a few).

He does this with a sprinkle of romanticism and a dusting with realism. Using his seemingly continual dissatisfaction with the world, Miyazaki aims to positively spark change and inspire. He insists that his films are not just flights of fancy; rather, he makes them to motivate the next generation to improve the world. “Children learn by experiencing…it is impossible to grow up without being hurt,” he writes. “Experiences like: accepting the duality of human nature, the importance of grit, conviction, and perseverance, and respecting nature and the land….For children willing to start, our films become powerful encouragement.”

WIT Life #268: New Japanese movies worth seeing

WIT Life is a periodic series written by professional Writer/Interpreter/Translator Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken CIR, 2000-03). She starts her day by watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese, and here she shares some of the interesting tidbits and trends along with her own observations.

The cherry blossoms have come and gone since the last time I posted, truly fleeting! I was lucky enough to enjoy them twice this year, both during a trip to Japan last month and at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden’s Sakura Matsuri earlier this month. To get through the long flight over the Pacific I like catching up on movies I missed, and I spent my outward voyage enjoying Oscar nominees and the return trip watching some new Japanese movies. During my inward flight two of the movies I picked, Judge! and The Little House, both featured one of my favorite Japanese actors, Satoshi Tsumabuki.

The former film features Tsumabuki as a young advertising agent who is forced by his boss to go in his place as an international judge for a worldwide TV Advertising Festival taking place in Santa Monica. By great coincidence, his boss’s name is Ichiro Otaki and Tsumabuki’s character’s name is Kiichiro Ota, giving them the same name if written Japanese-style with last name first. Ota points out that when abroad, names are written with first name before last name, but his boss ignores his concerns and sends him off. Another name coincidence is that Ota’s female co-worker Hikari has the same last name (in comparison to Kiichiro, she is amusingly referred to as the “talented Ota” by Otaki).

Kiichiro doesn’t have confidence in his English speaking ability, so he enlists Hikari to Read More