JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Dragon Quest Illustrations: 30th Anniversary Edition’

“Packed with over 500 iconic hand-drawn illustrations, this handsome, 240-page hardcover edition is a testament to the artist who helped set the visual standard for RPGs, raising the bar impossibly higher with each release.” (VIZ Media)

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02). Justin has written about Japanese arts and entertainment for JETAA since 2005, and is eagerly awaiting the 30th anniversary edition of All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku. For more of his articles, click here.

In the summer of 1988, the “World News” page in the debut issue of Nintendo Power magazine reported: “Ninjas and Kung-Fu Masters are no longer heros [sic] to Japanese players since they are now being replaced by warriors and sorcerers who bravely confront dragons with their swords and shields.”

With this mind-blowing description, my eight-year-old self was introduced to the world of Dragon Quest.

With over 71 million copies sold, this landmark video game series published by Enix (now Square Enix) is still going strong, with eleven main titles and thirty overall, securing a legacy that spans at least three generations. While role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons and Ultima existed long before game consoles invaded our homes, DQ was the one that rewrote the book and kept adding chapters that everyone from Final Fantasy to Pokémon copied from, long after its initial release in Japan in 1986 (and in the U.S. as Dragon Warrior in 1989).

Ironically, those other series are probably better known in the West, likely because for years Dragon Warrior lacked the “star power” associated with one man whose fame in Japan easily rivaled any game: Akira Toriyama. As the creator/illustrator/genius behind the back-to-back manga smashes Dr. Slump and Dragon Ball, Toriyama was coaxed by his trend-savvy editor to lend his talents to a new sword-and-sorcery title, marking a profound transformation (and future synergy) between the manga and gaming worlds. After DQ, nothing would ever be the same.

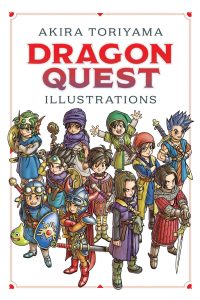

Now VIZ Media (the publisher of Toriyama’s work in English) brings us Dragon Quest Illustrations: 30th Anniversary Edition. Packed with over 500 iconic hand-drawn illustrations, this handsome, 240-page hardcover edition is a testament to the artist who helped set the visual standard for RPGs, raising the bar impossibly higher with each release.

Upon opening the book, the reader is treated to a gorgeous timeline history of every DQ title released at the time of its original publication in Japan. In a brief message from Toriyama, he reminisces that “back then, the RPG was much more of a niche genre that generally only appeared on PC. Even when they explained the concept to me, I still didn’t get it.” History has shown that Toriyama quickly got it, and readers can now enjoy three decades of package art, promotional illustrations and character designs bursting with originality on every page.

Retrogamers will be delighted to find that nearly half the book is dedicated to DQ’s classic 8- and 16-bit Nintendo eras (1986-1995), which comprise the first six games. The most striking thing when thumbing through the early monster designs (Slime!!) is how faithfully they were reproduced from the completed sketches to the screen—a testament to how much trust Enix had in Toriyama and his vision from day one, and a welcome shot of nostalgia to gamers everywhere.

Artwork for different formats and re-releases are included for all DQ titles like the Super Famicom and Game Boy ports of the first three games, and there are even a few monster designs that didn’t make the final cut (“Halloween Man” must be seen to be believed). Game bosses get their own pages, too, instantly sparking memories of hours and hours grinding away on the living room floor to earn experience points (and gold pieces) to defeat the likes of the Dragonlord, High Priest Hargon, and Archfiend Baramos (described in Toriyama’s notes as “a big old lizard”).

Also notable is that the pages on DQ II and III include Toriyama’s own tentative monster names written next to the designs, many of which were changed by Enix at the time of release. This provides some welcome insight into Toriyama’s creative approach (or super-nerdy game trivia, your choice).

Just as the series evolved, so did the visuals. Released in 1990, DQ IV sports character designs that are much more realistically proportioned, and for the first time, the supporting characters have given names. It’s no coincidence that these changes echoed Toriyama’s own maturing audience (the martial arts action of Dragon Ball Z was the hottest thing on Japanese TV at the time), while pushing the limits of the Famicom’s hardware. In fact, the next two games’ hero designs are dead ringers for Dragon Ball’s own next-generation good guys Son Gohan and Super Saiyan Trunks (not that we’re reading too much into this).

Digital coloring entered the picture with DQ VII. Released on the original PlayStation in 2000, Toriyama’s artwork now featured a richer palette atypical for manga, with more compact character designs and a stronger medieval influence. Released for the PlayStation 2 in 2004, DQ VIII ushered in 3-D graphics and cel shading, finally bringing a 360-degree in-game view of Toriyama’s creations to life (which inspired many new monster designs as a result).

Woven throughout the main series chapters are package art from spinoff titles like DQ Monsters, DQ Builders, and DQ Swords. The latter’s characters entertainingly resemble European runway models, a whimsical indulgence that Toriyama was clearly relishing. Most appreciated by this reviewer is a 1989 calendar illustration from Weekly Shonen Jump (the manga anthology magazine that serialized Dragon Ball) featuring the characters from the DQ anime series that actually aired in North America in 1990 for just 13 episodes.

While every piece of artwork here is a winner, as a book there are some flaws. The first is that, with few exceptions, every design here is “final cut,” so they don’t differ much (if at all) from what you see in the game, Japanese manuals or box art. The only exceptions are one page of non-player characters from DQ V (which went unused because they were “too distinct”), and small illustrations of a citadel and a ship; other than that, it’s mostly characters and monsters. Architecture, works-in-progress, alternate versions, and ancillary marketing drafts are pretty much absent here, save for some bonus illustrations at the end including a 1988 New Year’s postcard sketch of Toriyama, hunched over his TV and immersed in a test copy of DQ III.

In addition, there are no written reflections or insight into Toriyama’s own evolution and goals for the series. Perhaps he prefers to let his art speak for itself, but fans wanting to learn more (heck, pretty much anything) about the “why” will be disappointed. The only commentary provided is a four-page “Analysis of DQ Illustrations” section near the end by the editorial staff of V Jump, which provides the briefest of commentary for each main game title. Likewise, since this book is called Dragon Quest Illustrations, don’t expect a detailed chronicle of the games themselves, or how they revolutionized RPGs—or video game history—in turn. (Since one of these likely exists in Japan, perhaps this will be explored in a future companion volume from Square Enix, or in the inevitable 35th anniversary edition.)

The book ends with a single-page teaser for DQ XI (released worldwide on PlayStation 4 in September), and some final words from Yuji Horii, DQ’s equally legendary writer and game designer, who reflects that “getting Toriyama-san to do the character designs couldn’t have been more perfect. The monsters could’ve turned out scary, but instead they were charming, which made the battle screen all the more fun.” Fittingly, he has the final word: “Life itself is basically an RPG.”

For the eight-year-olds in all of us, may Dragon Quest run another 30 years.

For more on Dragon Quest Illustrations: 30th Anniversary Edition, click here.

For more JQ book reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.