JQ Magazine: Manga Review — ‘The Osamu Tezuka Story’

“Gargantuan in size at 928 pages (including detailed appendixes), this manga-format biography is a surprisingly quick read. Its fast-paced visuals and story provide a unique vantage to observe a legendary figure that leaves you energized after each sitting.” (Stone Bridge Press)

By Alexis Agliano Sanborn (Shimane-ken, 2009-11) for JQ magazine. Alexis is a graduate of Harvard University’s Regional Studies-East Asia (RSEA) program, and currently works as a program coordinator at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute of NYU School of Law.

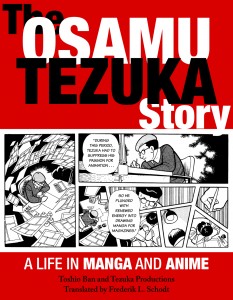

For many, the newest publication from Stone Bridge Press will seem like a long lost friend. Originally serialized in 1989 and completed in 1992, The Osamu Tezuka Story: A Life in Manga and Anime, written and illustrated by Toshio Ban in association with Tezuka Productions and translated by Frederik L. Schodt, is a book worth the wait. Gargantuan in size at 928 pages (including detailed appendixes), this manga-format biography is a surprisingly quick read. Its fast-paced visuals and story provide a unique vantage to observe a legendary figure that leaves you energized after each sitting. Whether you first learned about manga and anime yesterday, five years ago, or have been a diehard fan for decades, this book has something to offer.

Manga and anime artist Osamu Tezuka carries the weight that Walt Disney carries in the West. His vision, ingenuity, and motivation defined and propelled the bourgeoning manga and anime industry of the fifties, sixties, and seventies. This book follows Tezuka through it all: from his birth in Osaka in 1928 to his death in 1989, and everything in between. Through him, we see 1930s Japan and the rise of militarism, the authoritarian interwar, the penurious postwar, and the gradual rebirth and growth leading to the booming days of the 1980s. In his lifetime, Tezuka experienced it all—feast and famine, war and peace—and it is fervently captured in his artwork and stories.

This book is written and illustrated by Toshio Ban, a longtime animator and friend of Tezuka. Carefully researched and painstakingly detailed, Ban covers everything from Tezuka’s lifelong fascination of insects, his struggle balancing his academic passion of medicine, and his artistic passion of manga and anime, to his various commutes between Takarazuka City and Tokyo. While some details are lacking (for example, the reasons behind his first animation studio Mushi Production’s bankruptcy and financial problems), Ban has created a work exhaustive as it is fascinating.

As this manga reveals, Tezuka saw possibilities and inspiration from everything. For example, the 1947 Russian animation Konyok-Gorbunok (The Humpbacked Horse) inspired him to write one of his earlier works (Faust) and later the long-running manga series Hi no Tori (Phoenix). Other works, which began in a much more pedestrian fashion (at the request of publishers), led to the birth of signature characters like Astro Boy, whose eventual popularity took on a life of its own. Originally appearing as a supporting character in Atom Taishi (Ambassador Atom), this manga ran as a long-form story for years before it was rebranded in 1952 as Testuwan Atom (Mighty Atom) featuring shorter episodic situational dramas. From there, it was transformed again when Tezuka founded Mushi Production in the early 1960s.

Astro Boy’s compact episodic format translated well to anime. With a limited budget, timeframe, and staff, Tezuka revolutionized the animation industry which had once been a beautifully detailed, yet slow and laborious giant. Utilizing ingenious camera work, stock images, expressions and positions, Tezuka amped up the industry into the fast-delivering powerhouse it is known as today—the details of which you will have to find out for yourself by reading the book.

Particularly fascinating are Tezuka’s side projects, true works of experimental passion that may not have captivated the masses like his characters Astro Boy, Black Jack, or Kimba the White Lion (the inspiration behind Disney’s The Lion King), but are truly inspiring and evocative works of art. His short film Somewhere Street was designed as the animation studio’s initial “calling card,” a way to show the technical prowess of this fledgling animation studio. His short work Jump, a study in perspective and movement, is a work of whimsy that is surprisingly insightful. Legend of the Forest from 1987 combines a visual history of animation set to a soundtrack of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4. They are all available on YouTube (for now) and are stunning in their own right—a Tezuka you didn’t know.

In truth, the story seems a blur. At every great milestone in Tezuka’s life, one thinks, “Surely this is where things will calm down!” with the next page featuring a montage of Tezuka lounging somewhere in Hawaii. Instead, it’s back to the salt mines: The pace is relentless. Yet, amid the maelstrom and might, there exists a chilling underpinning of inadequacy not often explored. Tezuka was a man of passion, yet beneath it all, Ban hints at an artist seemingly insecure and desperate. In one notable scene, Tezuka poses the question, “Will my fans forget me?” Through the lens we now view Tezuka in—as a titan of the industry—such an idea seems preposterous. To “forget” Tezuka would be to forget manga and anime itself. Nevertheless, for the living and breathing Tezuka, the fight to remain relevant while achieving a transcendental vision (immortalized in more than 150,000 pages published in his lifetime) remained an eternal struggle.

Throughout his trials, this book keeps the momentum going as Tezuka builds worlds and blazes trails. New frontiers and distant horizons remain his motivation in a thicket of deadlines and the fog of all-nighters. Indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects of this work is the revelation of what exactly it means to be a manga artist, especially in the seventies. Instant ramen and energy drinks only begin to touch on the work culture that literally drove many to their death. This book is a dizzying dance reaching ever higher—until suddenly, it ends. Just as suddenly as Tezuka himself departed this world.

Will there ever be an end to Tezuka’s vision? Given his massive influence in postwar Japan and the rediscovering of his works (not to mention their eventual publication in English, which continues to this day), it seems unlikely. With his sudden departure, we have instead a visual history of a lifetime, proof of what passion and a life could be. It is the classic Japanese ethos: Tezuka never gave up on his dreams, and through reading this book, you are encouraged to do the same. After all, if Tezuka could do it through a lifetime of all-nighters, with a little grit and determination, so can we.

Read a sample of The Osamu Tezuka Story here. For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.