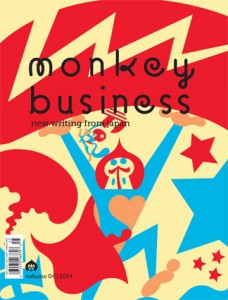

JQ Magazine: Book Review—‘Monkey Business Volume 4’

“In part, this collection is a quest. And it is a quest into questions, many of which straddle the thin lines of life, all the while hurling us through time and space, water and air, pain and pleasure, and beginnings and ends.” (A Public Space)

By Brett Rawson (Akita-ken, 2007-09) for JQ magazine. Brett is a writer, translator, and volunteer. He currently lives in New York, where he is pursuing an MFA in creative writing at The New School and is the professional development chair for the JET Alumni Association of New York. If you have job opportunities for JET alums, an interest in presenting at JETAANY’s annual Career Forum, or want to collaborate on professional endeavors, contact him at career@jetaany.org.

Meet Volume 4 of Monkey Business International: New Writings from Japan, a collection of 23 works that will take you on a wild ride through the literary landscape of Japan. In fact, it goes beyond the boundaries of Japan—as summed up by co-founders Motoyuki Shibata and Ted Goossen in the preface, Monkey Business International is “60 percent contemporary Japan, 20 percent contemporary American and British, and 20 percent modern classic Japan,” though of course not every hybrid has a categorical home.

In part, this collection is a quest. And it is a quest into questions, many of which straddle the thin lines of life, all the while hurling us through time and space, water and air, pain and pleasure, and beginnings and ends. Take for example the short story “The Man Who Turned into a Buoy” by Masatsugu Ono. The title itself seems to whisper, loosen your grip, encouraging us to suspend our disbelief and simply enjoy as our perspective gets gently nudged out of ordinary orbit.

The tale transports us to a tiny town nestled between the shoreline and the hills, which is overrun with frolicking monkeys who descend to steal food left on graves, but have been known at times to talk with villagers, and sometimes in the voice of the deceased. This town also observes the tradition of the body as a buoy—a single man tasked with the job of nakedly floating at the edge of the inlet during the day, issuing warnings to people who exit the bay. The man who turned into the buoy is the narrator’s grandfather, and his story is recounted through the grandmother in a dense dialect that is beautifully captured by translator Michael Emmerich.

When the narrator asked why the grandfather was the chosen one, his grandmother replied, “Mabcuz hehzgot maw hairn anyone, anit blackrn coal lemtel—ontopwhat heh hadsum normous head onjhit sholds, ahuy thatee did” (maybe because he’s got more hair than anyone, and it’s blacker than coal let me tell—on top of that he had some enormous head on his shoulders, ay that he did). There is little that’s certain about the history and order of the buoy—how the human buoy began, what role it really served, why the grandfather was chosen and by whom, and why the grandfather’s reply was a simple “I see.” The narrator guides us through his thoughts, as he wonders what it means, beneath the surface, to stay in place, anchorless, and serve as a marker for others when you yourself have no marker. But as the narrator says, “no one really knows the truth, and the presence of an explanation doesn’t change reality.”

The other short stories take you to faraway worlds of their own, some of which, similar to the story above, make it clear from their titles alone: “The Girl Behind the Register Blows Bubbles” by Keita Jin; “The Little Girl Blows Up Her Pee Anxiety, My Heart Races” by Mieko Kawakami; “Demon Beasts” by Gen’ichiro Takahashi; “The Bears of Mount Nametoko: A Remix of a Tale by Kenji Miyazawa” by Hideo Furukawa; and “The Restaurant of Many Orders” by Kenji Miyazawa, to name a few. But there is much more than simply the short story. There is Richard Powers’ essay, “The Global Distributed Self-Mirroring Subterranean Neurological Soul-Sharing Picture Show: On Haruki Murakami’s Fiction,” which will test the powers of your concentration as he offers neurological insight into why Murakami has grown so globally loved; Mina Ishikawa’s “The Lighthouse on the Desk,” which are tanka poems that interact with Genji Ishikawa’s The Lighthouse from 1914; the manga “Tailors’ Dummies” by Brother and Sister Nishioka, which is based on the short story by Bruno Schulz, and much more.

I read through the collection in a single day, though it feels like that day has yet to end, as the feelings from these stories continue to float around the periphery of my perspective. As I sank into each story, I often felt my mind wander down the corridors of my memories of living in Kisakata-machi in Akita, a coastal town that sits between the Sea of Japan and Mount Chokai. As these stories straddled lines of life, language, familiarity, and reality, I recalled how it felt to move and live somewhere unfamiliar, but how that feeling slowly faded away, as the people, place, culture, and country came into a familiar focus. It is odd how the magical world of words in these stories, intangible as it sometime seemed, caused me to recall such palpable and personal moments.

As I closed the back cover, I hopped online to order the first three volumes. There is still much mystery to the monkey and its musing, but the first story, “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey” by Craft Ebbing & Co., offered a hint of help by spelling things out for us: halve monkey and you get mon and key; mon means my in French or gate in Japanese; so perhaps we have my key or gate key; but on the QWERTY keyboard, the Japanese characters mo and n lie on the keys marked with Roman letters m and y; and so perhaps we have in our hands two signs that say the monkey is our key. I don’t know what the monkey unlocks, but I do know one thing for sure: there is no such thing as too much Monkey Business.

For those living in New York, come meet those responsible for all this Monkey Business, as contributing authors Toh EnJoe, Hideo Furukawa, Laird Hunt, Matthew Sharpe, founding editors Motoyuki Shibata and Ted Goossen, and contributing editor Roland Kelts (Osaka-shi, 1998-99) come to celebrate the launch of Volume 4 from May 3-5 (see full schedule here).

For more JQ coverage of Monkey Business, click here.

Comments are closed.