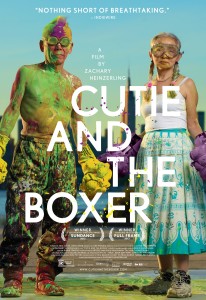

JQ Magazine: Film Review – ‘Cutie and the Boxer’ Pairs Sparring Partners in Life, Art

“Director Zachary Heinzerling spent five years with the Shinoharas in the making of his movie, and it has been recognized with critical praise and honors including the U.S. Documentary Directing Award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.” (RADiUS-TWC)

By Stacy Smith (Kumamoto-ken CIR, 2000-03) for JQ magazine. Stacy is a professional Japanese writer/interpreter/translator. She starts her day by watching Fujisankei’s newscast in Japanese, and shares some of the interesting tidbits and trends together with her own observations in the periodic series WITLife.

Director Zachary Heinzerling’s debut documentary is the captivating Cutie and the Boxer, which follows two New York-based Japanese artists who have been married for over 40 years. It stars Ushio and Noriko Shinohara, a couple separated in age by two decades who have a truly unique union. They alternately bicker and support each other, but you get the sense that their respective existences are necessary for the other to survive. As wife Noriko puts it, “We are like two flowers in one pot,” meaning that when things are going well they are essential for each other’s flourishing, but when things are not they are fighting over limited space and nourishment.

Ushio (a.k.a. Gyu-chan) is an artist who was active in the avant-garde art movement, and is known for his boxing paintings and motorcycle sculptures. He achieved great fame in Tokyo before moving to New York to test his skills in the States. He was 40 at the time he met Noriko, who was 19 and had come to New York to study art. Things happened quickly between them, and soon they were married with a son, Alex. Noriko put aside her artistic aspirations to help Ushio in his career and raise Alex, thus curbing the potential for her own success.

Meanwhile, Ushio was floundering in building a name for himself as an artist in his new country. Despite the fact that he had become a father, he didn’t want to move beyond his old ways of drinking with friends and discussing philosophies regarding art. One of the most poignant and candid scenes in the film is when Ushio becomes quite drunk at one of these gatherings and emotionally describes both the pain and sublime pleasure he receives from creating art, saying that he would rather die than do anything else with this life. It is one of the film’s truly heartbreaking and inspiring moments.

Noriko’s identity as an artist comes to occupy a central role in the story when Heinzerling focuses on her Cutie and Bullie series of drawings, based on the progression of her years with her husband. With Ushio quitting drinking seven years ago and Alex now an adult (apparently having inherited his father’s alcoholic tendencies), she has the ability to devote time and energy to her own work which is special in its own right. When a gallery owner visits the Shinoharas to discuss the prospect of an upcoming show featuring Ushio, Noriko appeals to him to include her work as well. The scene feels like a microcosm of the underlying struggle characterizing the dynamic between them. (Author’s note: I had the opportunity to interpret for Ushio at an event earlier this year at the Museum of Modern Art, and at the time I found Noriko to be nothing but a supportive presence, which makes me wonder how much of their combative relationship is crafted and to what extent it actually is as turbulent as depicted.)

Heinzerling spent five years with the Shinoharas in the making of his movie, and it has been recognized with critical praise and honors including the U.S. Documentary Directing Award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. The viewing experience is enhanced by a fabulous score by Yasuaki Shimizu, so make sure to check it out!

Cutie and the Boxer opens Aug. 16 in New York (Lincoln Plaza Cinema and Landmark Sunshine Cinema) and Los Angeles (Nuart Theatre). For more information, visit www.facebook.com/cutieandtheboxer.

Comments are closed.