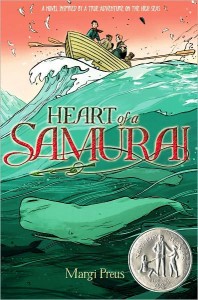

JQ Magazine: Book Review – ‘Heart of a Samurai’

“Many people join the JET Program looking to form international bonds between their home countries and Japan, but Manjiro Nakahama faced bigger challenges into trying to end Japan’s isolationist policy. ‘Heart of a Samurai’ gives you a fun glimpse of one of Japan’s most important historical figures.” (Abrams)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-2010) for JQ magazine. Rashaad worked at four elementary schools and three junior high schools on JET, and taught a weekly conversion class in Haguro (his village) to adults. He completed the Tokyo Marathon in 2010, and was also a member of a taiko group in Haguro.

You might know that under the policy of sakoku, no Japanese were permitted to leave the country. So when Japanese people were finally able to do so, it must have been a fascinating story. And thanks to Margi Preus, people have an easy-to-read tale about one of the first Japanese to venture outside of the country’s borders.

Preus’ book Heart of a Samurai offers a look into the life of Manjiro Nakahama, a fisherman-cum-aspiring samurai whose life is turned upside down when his boat is shipwrecked during an 1841 fishing trip. He and his four comrades are stranded on a remote island until members of an American whaling vessel arrive.

It was aboard the John Howland that Manjiro first learned about a world previously foreign to him. Unlike his comrades, the ever-inquisitive Manjiro is not scared of “butter stinkers” (a derogatory term for foreigners) and he learns English so quickly, he forms a bond with ship captain William Whitfield. Whitfield eventually takes Manjiro back to the United States, where the young man lives with the captain’s family. After spending several years exploring the world by sea, Manjiro eventually returns to Japan to accomplish his goal.

This book will resonate with people because it addresses the theme of being shocked at the world’s differences—some of which are hilarious (Aboard the John Howland, Manjiro is stunned by the existence of buttons, pockets, forks and knives while later expressing similar astonishment by seeing men wearing watches) and some that are not so funny (Manjiro is stunned to see segregation in a church). And in addition to adjusting to a culture where everything seemed to changing, Manjiro must also tackle racism and a new language while working to prove himself to people in a new country.

Although the book isn’t a short one, it is very much geared toward children—many of whom might be unfamiliar with Japan. Fortunately, Preus lists the definitions of Japanese terms used in the book, which is probably helpful even for those who have lived in the country. So while the book does a serve a nice introduction to those interested in a fascinating aspect of Japanese history, it definitely doesn’t satisfy those looking for a real biography of Manjiro. (What happened after he became a samurai?) Heart of a Samurai is heavy on dialogue, not facts, so you might have a sense of wondering what really happened when you read the book.

But if you tackle this book with the right expectations, it is an excellent read. The relatively short chapters make Heart of a Samurai an easy story to read and because Preus doesn’t go heavy on facts and figures, she does a good job of holding the reader’s attention in the book. Not only does Preus take you into the mindset of many Japanese during that time period (one of Manjiro’s friends refers to foreigners as “barbarians who can’t be trusted” and they thought foreigners could do nothing but poison the minds of Japanese), but also into life on a ship: the dialogue is dotted with sailor slang.

Many people join the JET Program looking to form international bonds between their home countries and Japan, but Manjiro Nakahama faced bigger challenges into trying to end Japan’s isolationist policy. Heart of a Samurai gives you a fun glimpse of one of Japan’s most important historical figures.

For an NPR Backseat Book Club feature on Heart of a Samurai, click here.

Comments are closed.