Benjamin Davis (ALT Chiba-ken, 2006-07, CIR/PA Chiba Kencho, 2007-09) is a freelance writer/researcher, translator, renaissance man and jack-of-all-trades based in rural Chiba-ken. He can be contacted at davis.benjamin.j@gmail.com and is always on the lookout for new and interesting projects.

Benjamin Davis (ALT Chiba-ken, 2006-07, CIR/PA Chiba Kencho, 2007-09) is a freelance writer/researcher, translator, renaissance man and jack-of-all-trades based in rural Chiba-ken. He can be contacted at davis.benjamin.j@gmail.com and is always on the lookout for new and interesting projects.

“Setsubun, Bean-tossing, and the Old Japanese Calendar”

This February 3rd, when he gets home from work, my friend Mr. Watanabe will be chased out of his own house, by his own children, who will shout at him and throw dried beans in his face.

No, this is not some clever new trick on the children’s part to get back at him for enforcing their bedtimes. On the contrary, it will be something he planned in concert with them days earlier. He himself will be wearing a demon mask, his wife will be encouraging the children on in the background, and the shouts in question will be repeated cries of “Demons out, fortune in!”

You see, this bean-throwing and shouting is actually an ancient Japanese tradition called “Setsubun” (節分). It is a ritual whose objective is to chase out the malevolent spirits that may have built up like dust bunnies in the dark corners of the house over the year and invite in good fortune for the coming year.

To make the experience more symbolically tangible, a male member of the house may dress up as  a demon and volunteer to be an object of expulsion-by-legume. Depending on regional taste and individual enthusiasm, severed sardine heads may be hung from the door to keep said spirits – and perhaps nosey neighbors as well – from being tempted to wander back in again when the dust settles. (Apparently ghosts don’t like bad smells.) Then once all the freeloading malevolent spirits have been kicked to the curb, each member of the household eats their age in beans in hopes of having good luck and health until the next Setsubun rolls around. Also, depending on the family, they may face the predetermined “auspicious direction of the year” and eat a special kind of rolled sushi called ehomaki.

a demon and volunteer to be an object of expulsion-by-legume. Depending on regional taste and individual enthusiasm, severed sardine heads may be hung from the door to keep said spirits – and perhaps nosey neighbors as well – from being tempted to wander back in again when the dust settles. (Apparently ghosts don’t like bad smells.) Then once all the freeloading malevolent spirits have been kicked to the curb, each member of the household eats their age in beans in hopes of having good luck and health until the next Setsubun rolls around. Also, depending on the family, they may face the predetermined “auspicious direction of the year” and eat a special kind of rolled sushi called ehomaki.

Mr. Watanabe, whose children have reached ages 2 and 5 respectively, believes that their youth is an important chance to transmit traditional aspects of Japanese culture (especially the fun ones). Indeed, the festival enjoys most popularity across Japan with families with young children, in a way that is not so terribly different from traditions of the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus.

Well, that’s all well and good and jolly cultural, you might say, but why the beans? And why pick some random day in February for a spiritual house cleaning?

Let’s talk about the latter question first. The old Japanese calendar system is complicated to the extent of perhaps warranting a grad school thesis or three, but Setsubun is as good an excuse as any to talk about a few of its more interesting points.

Generally, when you are talking about months and dates in old Japan, e.g. the 15th day of the 7th month (that’s Obon, for the curious), you’re talking about a lunar calendar with months based on the phases on the moon. The problem with a purely lunar calendar is that with moon cycles lasting 29.5 days or so – and thus a lunar year having either 354(ish) days or 384(ish) days depending on the year – the calendar doesn’t line up very consistently with seasonal phenomena, and therefore isn’t terribly useful as an agricultural guide (for determining harvest and planting times, etc.).

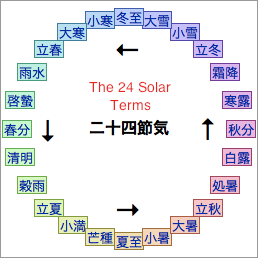

So the ancient Japanese kept track of solar events as well. In addition to the solstices and equinoxes that our Gregorian calendar considers to be the break points between the seasons, they also kept track of the halfway points between those markers, sometimes called “cross-quarter days”, and of even more markers between those as well. In fact, they broke the year down into 24 different solar terms of about 15 days each (more technically, 15 degrees of solar longitude each), with individual names reflecting seasonal events expected around that time of year, such as “Rain Water” (雨水), “Insects Awaken” (啓蟄), “Grain Fills” (小満), “Frost Descends” (霜降), “Light Snow” (小雪), and “Heavy Snow” (大雪).

So the ancient Japanese kept track of solar events as well. In addition to the solstices and equinoxes that our Gregorian calendar considers to be the break points between the seasons, they also kept track of the halfway points between those markers, sometimes called “cross-quarter days”, and of even more markers between those as well. In fact, they broke the year down into 24 different solar terms of about 15 days each (more technically, 15 degrees of solar longitude each), with individual names reflecting seasonal events expected around that time of year, such as “Rain Water” (雨水), “Insects Awaken” (啓蟄), “Grain Fills” (小満), “Frost Descends” (霜降), “Light Snow” (小雪), and “Heavy Snow” (大雪).

(If you are interested in a complete list and more explanation of these solar terms, check out:

http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/modules/xwords/images/uploads/EOS070511Lb.pdf and http://www2.gol.com/users/stever/calendar.htm#terms

Another interesting fact to note is that, while the Gregorian calendar views the equinoxes and solstices as the breaks between seasons, the old Japanese calendar viewed them to be the midpoints of seasons. This makes sense in a way – then the longest night of the year is in the dead middle of winter (whereas for us, for different reasons, the same day is considered only to be the first day of winter). Thus the break points between seasons for the ancient Japanese would instead be those cross-quarter days mentioned before.

Coming back to Setsubun, if you’ve been doing a lot of mental math along the way, you might have guessed that February 3rd falls suspiciously close to the cross-quarter day between the winter solstice and the spring equinox (somewhere between Feb 2-7 depending on the year), in other words, according to the ancient Japanese, the beginning of spring.

Actually, the word “setsubun” (節分) simply means “division of parts” and originally referred to any break between any of the seasons, but over time came to specifically refer to the last day before Risshun (立春), the solar term marking the beginning of spring. So it’s not just any old random day after all – it’s the eve of spring.

But wait, you might say, it’s all well and good that Setsubun turns out to be the eve of spring and all, but doesn’t the actual content of the ritual sound more like something you’d expect around the run up to the Japanese New Year? You know, a sort of spiritual house cleaning to go along with the customary physical house scrubbing that most Japanese families do around that time in order to start the new year with a fresh slate?

If your thoughts turned in this direction, well, bingo – award yourself some mytho-anthropological sleuthing points. The Japanese New Year has only lined up with the Gregorian New Year (January 1st) since around the time of the Meiji Restoration. Before that, it lined up with Chinese lunar calendar. If you’ve ever paid much attention to Chinatown and its festivities, you may have noticed the bustle of Chinese New Year usually happens sometime in February – i.e. in the (ancient Japanese) spring, not in midwinter. So, while Setsubun is a solar calendar event and New Years was a lunar calendar event, Setsubun still usually fell sometime in the days before New Years and was therefore considered not just the eve of spring, but a sort of New Years Eve as well.

If your thoughts turned in this direction, well, bingo – award yourself some mytho-anthropological sleuthing points. The Japanese New Year has only lined up with the Gregorian New Year (January 1st) since around the time of the Meiji Restoration. Before that, it lined up with Chinese lunar calendar. If you’ve ever paid much attention to Chinatown and its festivities, you may have noticed the bustle of Chinese New Year usually happens sometime in February – i.e. in the (ancient Japanese) spring, not in midwinter. So, while Setsubun is a solar calendar event and New Years was a lunar calendar event, Setsubun still usually fell sometime in the days before New Years and was therefore considered not just the eve of spring, but a sort of New Years Eve as well.

To sum it all up, “Setsubun” is just one part of a broad New Year’s cleaning (in other words, “spring cleaning”) package. It’s just that at some point New Year’s moved and left poor, lonely Setsubun behind.

…And the beans?

Interestingly enough, the ancient Romans actually had an in-some-ways similar exorcism rite, called the Feast of the Lemures, where they would throw beans to repel the spectres of the restless dead. So maybe there is just something about beans that malevolent spirits don’t like. Or maybe beans, along with seeds and eggs and the like, are just fairly obvious symbols of new life and the power therein (a power which might reasonably be assumed to be effective against the unruly dead and moldy), and this is just a case of parallel evolution of symbolism. You decide.

Post Script: If you find yourself in Japan on a February 3rd (or sometimes 4th, but not this year) and you are interested in Setsubun but don’t have a host family to enjoy the holiday with, try wandering down to your local Shinto shrine. If you time it right (best to ask a local), you may just find scores of people congregating there waiting for the priests and/or local dignitaries to rain beans upon them. Watch out for harder, heavier, non-bean objects like coins and snack foods that are sometimes mixed in for fun, however. And for unstoppable grannies diving for the free stuff and rare prize vouchers. Happy Setsubun-ing!

• Kokugakuin University, The Encyclopedia of Shinto. http://eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp/

• S. Renshaw and S. Ihara, “Setsubun in Japan”. http://www2.gol.com/users/stever/setsubun.htm

• ibid., “The Lunar Calendar in Japan”. http://www2.gol.com/users/stever/calendar.htm

• Leonhard Schmitz, “The Lemuralia”. From A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. http://www.ancientlibrary.com/smith-dgra/0687.html

• My coursework as a religious studies major at Cornell University

(All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and shared under public license: http://commons.wikimedia.org/ )

one comment so far...

Wow very informative.