JQ Magazine: ‘Angel’s Egg’ 4K Restoration: A Reverie Reborn in Dolby Cinema

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for JQ magazine. Justin has written about Japanese arts and entertainment for JETAA since 2005. For more of his articles, click here.

Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg is one of those films that people talk about in a lowered voice, as if it were a mystery that might vanish if confronted too directly. It is a film of austere beauty and radical quiet—70-odd minutes of shadowed corridors, abandoned cathedrals, fossilized leviathans, and two nameless travelers: a girl who cradles a giant egg as if it were her entire future, and a boy who cannot stop asking what’s inside.

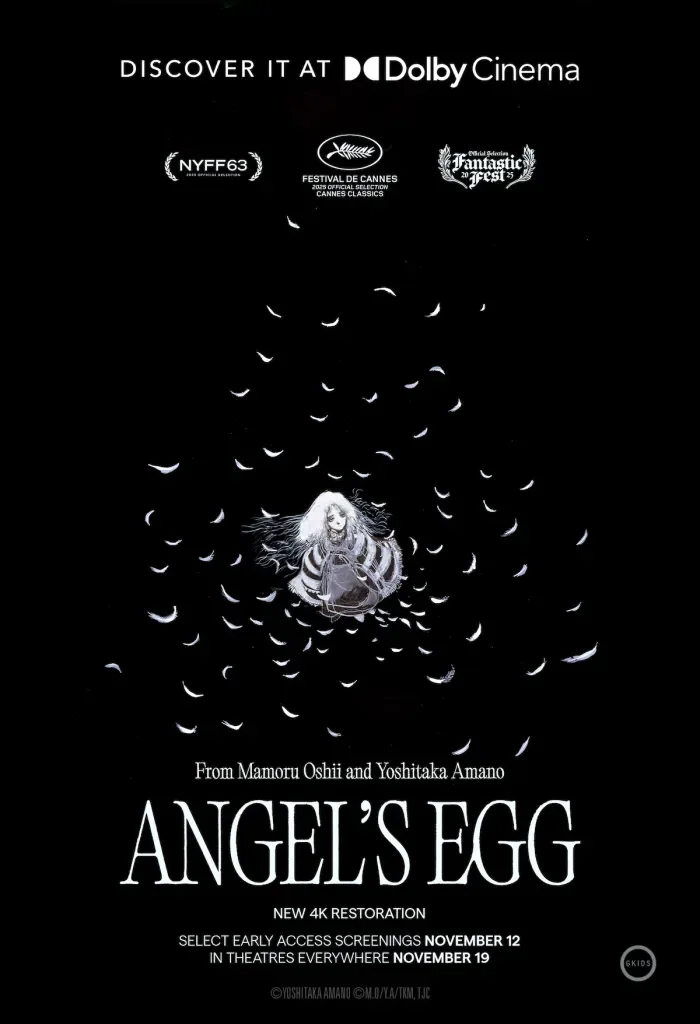

Released in 1985 and long unavailable through official channels in North America, Angel’s Egg has gathered its legend through bootleg tapes, festival whispers, and the occasional late-night screening. Now, four decades on, it returns today (Nov. 19) in theaters nationwide in a new 4K restoration supervised by Oshii and presented nationwide by GKIDS, which included Dolby Cinema early access engagements before the general theatrical rollout. For a film that has lived so much of its life in the margins, the chance to experience it in a calibrated premium room with Dolby Vision and Atmos support feels almost paradoxical—and absolutely right.

This anniversary run isn’t just a new coat of paint. The restoration—which debuted on the 2025 festival circuit and now arrives coast to coast—was reconstructed from the original 35mm materials, with a Dolby Cinema version created alongside a rebuilt soundtrack that expands the original mono presentation into 5.1 and Dolby Atmos options. That last detail may raise eyebrows for purists, but in practice the approach respects the film’s fundamental quietude; it simply gives the silence more dimensions.

To remember Angel’s Egg in the context of anime history is to remember how unstandardized the medium felt in the mid-1980s. It premiered in a decade when the OVA market was exploding and when directors like Oshii and artists like Yoshitaka Amano (Final Fantasy, Vampire Hunter D) were testing the boundaries of animation’s visual grammar. The film’s surface—textured stone, dripping water, the faint pulse of bio-mechanical curiosities—speaks in symbols rather than exposition. There is barely any dialogue. The camera (or rather, Oshii’s implied lens) prefers long lateral moves, as if pacing the nave of an endless church, and the compositions are arranged like prints: light carved out of darkness, characters dwarfed by architecture, the egg always nestled in white cloth at the frame’s center.

When viewers call the film “obscure,” they don’t just mean it’s hard to find; they mean it resists the usual ways we talk about plots. If Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell (1995) became the textbook for cyber-philosophy in animation, Angel’s Egg is the poem scrawled in the margins. The imagery anticipates later techno-gothic strains of anime, but without the anchor of a conventional narrative. In this sense, its return to theaters matters historically: one rarely sees repertory engagements for 1980s anime outside of a handful of well-known titles, and the film’s own distributors underscore how rarely screened it’s been in any official capacity. Seeing it at scale isn’t a curiosity; it’s an act of historical restoration.

Oshii’s collaboration with Amano yields a film that looks simultaneously medieval and futuristic. Statues of saints are strapped to rolling platforms and carted through fog-wet streets; hunters hurl harpoons at shadow-fish that pass across stone facades like projected ghosts; the girl and the boy ride a gargantuan, half-submerged machine that could be a cathedral or a vessel or a fossilized beast. The film’s religious aura—crosses, chalices, a literal ark—threads through its central question: does faith require the egg to remain closed, or the courage to break it? The boy, carrying a rifle and speaking in riddles, keeps needling: “What’s inside?” The girl maintains her vigil.

What’s remarkable, especially on a big screen, is how the movie makes time feel tactile. Shots hold until your breathing matches the drip of water; the rhythm of footsteps through an empty hall becomes as musical as Kenji Kawai’s glassy, ascetic score. And then, at intervals, Oshii punctures the stillness with kinetic episodes: a barrage of thrown spears; a dissolve-drunk montage of monuments and bones; an unforgettable nocturne of the boy swinging the egg like a hammer. These moments carry a kind of moral vertigo that’s hard to feel at home; they need the dark, the scale, the sense that the film surrounds you.

Read More