Justin’s Japan: Q&A with Yuki Chikudate of Asobi Seksu

By

JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his pages here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

Formed in New York City in 2001, the band Asobi Seksu and its core members Yuki Chikudate (vocals, keyboards) and James Hanna (guitar) cut their teeth in the indie shoegaze and dream pop scene as it graduated from a dense, textured guitar-based sound to a more abstract, atmospheric approach.

Fluorescence, the band’s fourth and latest studio album, hits stores today (Feb. 15). I caught up with Chikudate prior to the band’s sold out show at New York’s Mercury Lounge later this week for this exclusive interview.

What kind of goals did you and James have recording Fluorescence?

We knew that we were interested in making an album that better captured what we sound like live. We wanted it to be colorful.

How did you approach the recording compared to your other albums?

The approach was to let go and have fun. I think we felt a lot more relaxed this time—it was summer.

Do you have any other special plans for promoting the album in addition to touring?

Hoping to play some festivals this year—outdoor shows are the best!

I read that you grew up in Southern California and attended a school for children of Japanese expatriates who planned to return home after several years abroad. Was this your first brush with Japanese culture outside the home, and how do you think the experience influenced your view of Japan or the way this aspect of its society operates?

I was born in Japan, so no, it wasn’t my first experience with Japanese culture outside my home. My view of Japan was that all my family was there. Sometimes I wished that it wasn’t so far away. As a kid, the strict disciplinary nature of Japanese school sucked!

Click here for the rest of the interview.

National AJET’s “Life After JET”: Vanessa Villalobos

National AJET shares former JET participants’ experiences – and a little advice – with current JETs in their new monthly interview, Life After JET. Contact lifeafterjet [at] ajet.net to be featured in future posts.

*************

This month, Life After JET profiles former Tochigi ALT, Vanessa Villalobos. After completing JET and obtaining a CELTA qualification, Vanessa moved to Peru where she taught for 15 months. She then returned to the UK to train as a secondary school level English teacher at King’s College London, earning a Postgraduate Certificate of Education.

However, instead of starting a more conventional career in education, she started her own business. She “now works to connect the UK and Japan in London with her two companies – IsshoniLondon.co.uk, which provides tutoring services, and JapaneseLondon.com, which is a central hub for all Japan-related happenings in London.” In addition, she is involved in JETAA London, serving as the Communications Officer and organizer of the Creative Entrepreneurs’ Group.

Vanessa shared with us a little bit about her experience on JET and since, plus advice for budding bloggers, entrepreneurs, or any JET trying to figure out what comes next…

NAJET: First, can you tell me a little bit about your experience on the JET Programme? It looks like you were an ALT in Tochigi from 2000-2003 — Any highlights or projects that you’re really proud of?

Vanessa Villalobos: Being a ‘one-shot’ ALT meant that I had quite an exhilarating life; cycling around Tochigi-shi with my bike baskets over-brimming with games, flashcards, worksheets, etc. I was based in the BOE along with two other ALT colleagues. We took it in turn to visit all the junior high schools and elementary schools in the area. Like so many ALTs I found elementary school teaching an absolute delight – if absolutely exhausting!

In the BOE, we also designed the English curriculum and materials for 15 elementary schools. It was so satisfying to be responsible for the syllabus right from first ideas to classroom delivery.

NAJET: Before becoming an ALT, did you know that you’d still be working with Japanese/UK relations even years after leaving JET?

Vanessa: No! But I have always been fascinated by communication, language, and international relations so I am thrilled that JET gave me chance to develop my skills and interest.

NAJET: Why did you first decide to start your blog, Isshoni London?

Vanessa: I experimented with blogging in Japan, and then wrote a successful year-long travelogue in Peru, but after coming back to the UK in 2005 I felt at a bit of a loss and stopped writing. I still really missed Japan and started to look for Japan-related things, events and communities in London. Much to my excitement, I found a wide range of information and opportunities. Even so, I kept missing out on things because that information was so spread out. I searched on the internet, collected little snippets from newspapers and magazines, grabbed brochures, scribbled down info from tube posters, and realised the gap in the market for a ‘one-stop-shop’ website where you could go to find out everything about Japan-related stuff in London.

‘Isshoni London’ is the name of my English-Japanese language tutoring company, and the blog was attached to it to provide extra information.

Click here for the rest of the interview.

JETs in the News: Lars Martinson featured in Japan Times article on ex-pat comics

********

JET alum/cartoonist Lars Martinson (Fukuoka-ken 2003-2006), author of the graphic novels Tonoharu: Part Two and Tonoharu: Part 1, is the focus (along with Adam Pasion, author of the Sundogs anthologies) of a thoughtful Japan Times article by Gianni Simone on comics about Japan “that tell it like it is.”

Here’s the link to the article: http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fl20110205a1.html

And below are a few excerpts about Martinson from the article:

The comic life of expats in Japan

Americans Lars Martinson and Adam Pasion tell it like it is with cutting-edge manga

By GIANNI SIMONE Special to The Japan Times

Tales of expat life in Japan all too often get blown out of proportion and quickly become picaresque adventures that little resemble real life.

**********

Luckily for us, many comic artists who have lived here seem to be more level-headed and have tackled the subject with a more realistic, no-nonsense approach.

**********

As the title suggests, “Tonoharu: Part Two” is not Martinson’s first foray in the field of expat comics: He self-published the first volume of this four-part saga in 2008 thanks to a grant from the prestigious Xeric Foundation.

Martinson, 33, first arrived in Japan in 2003 to work as an assistant language teacher, and spent the next three years working at a junior high school in a small town in Fukuoka Prefecture. His second stint in this country was in 2008 when he studied East Asian calligraphy under the auspices of a two-year research scholarship from the Japanese government.

Travel had played a pivotal role in his life (he had lived in Thailand and Norway as well), so when he came up with the idea of producing a graphic novel, he decided to make foreign travel a central theme.

“I planned from the start to turn my Japanese experience into a comic,” Martinson says, “even though I didn’t want it to be a mere autobiographical story. So I chose a 20-something American like me as the protagonist, but added a fictional group of eccentric expatriates living in the same rural Japanese town.”

At times living in the middle of nowhere was a challenge. Still, Martinson has no regrets about those three years spent in Kyushu.

“I’m actually a city slicker,” confesses Martinson, “and would love to live in a huge city in Japan at some point. Also, I’m sure that expat communities are awesome, but they can also separate you from the native population. When you live out in the country, you don’t have the option to just hang out with other Westerners, and this can force you to get involved in the host culture in ways you probably wouldn’t otherwise.”

Click here to read the full article: http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/fl20110205a1.html

Click here to read more JetWit posts about Lars Martinson:

Click here for Lars Martinson’s official blog/website: http://larsmartinson.com

National AJET’s “Life After JET”: Andrew Sowter

National AJET shares former JET participants’ experiences – and a little advice – with current JETs in their new monthly interview, Life After JET. Contact lifeafterjet [at] ajet.net to be featured in future posts.

National AJET shares former JET participants’ experiences – and a little advice – with current JETs in their new monthly interview, Life After JET. Contact lifeafterjet [at] ajet.net to be featured in future posts.

*************

This month, we further explore ways to build a teaching career in Japan from the JET experience. We interviewed Andy Sowter, a former-Prefectural ALT who taught at high schools and elementary schools for four years in Nara. After completing a Masters Degree in Applied Linguistics / Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL), he is now a lecturer at Kwansei Gakuin University in their Intensive English Program.

Andy recommends that JET participants looking to use JET as a springboard to teach at a Japanese university need to start preparing early. Many universities look for experience presenting and publishing and “the Mid-Year Training Seminars are a good place to start.” In addition, he recommends that university job-seekers “join JALT and attend a few meetings to get a feel for the people you will be competing with for jobs.” For more advice from Andy, see the full interview or check out AJET’s Life After JET links page to find more information about the qualifications, resources, etc mentioned in this article.

National AJET: I know that you started working on your Masters while on JET. Since you didn’t have a background in linguistics before that, did you need to do any extra preparation?

Andy Sowter: I started doing my Masters during my 3rd year of JET, I finished JET after my 4th year to complete my Masters full time in Australia. Working and studying with a young family was difficult [so take] advantage of the extra free time that JET often gives you to study (either Japanese or a qualification).

To apply, I had to write a letter to the program chair stating the reasons why I thought I would be able to complete a degree in Applied Linguistics coming from a science-based background. Before applying I corresponded with the program chair to make that personal connection, I think this helped. However, I did also have a CELTA degree and three years of teaching experience to back up my application.

I was very happy with my results as I think they reflected the amount of effort I put into my studies. Seriously, anyone who decides they want to do further study has to commit, it takes a huge amount of time and effort.

NAJET: Can you tell me a little bit about your Masters programme?

Andy Sowter: My program was done through an Australian-based university called Griffith University. They had a distance education masters program [that was recommended by other JETs]. The program was designed to be completed part time over two years. It was completely course based (i.e. no thesis, just huge assignments). Two of the courses required evaluation of classroom teaching and lesson planning. I chose to go back to Australia to complete these but I could have done it externally if I could have found someone here in Japan willing and qualified to do so. By going back to Australia and completing my courses internally I managed to complete my degree in 18 months.

NAJET: What kind of requirements are there for teaching in Japanese universities?

Andy Sowter: It is getting harder and harder to get jobs as student numbers decline. To succeed in the Japanese university system you need a Masters Degree. In addition, you [must have] teaching experience in a university, [be published], [have Japanese language proficiency], and contacts [to] acquire better teaching positions.

When I started out, I took part time jobs. I managed to get some publications and made good contacts. After a year teaching part time, I [got] a full-time contract position and then relatively quickly a second better full-time (contract) position (my current job).

Click here for the rest of the interview.

Justin’s Japan: Interview with Jazz Pianist Marcus Roberts

By JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his NY Japanese Culture page here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

Blind since the age of four, at 21 years old Marcus Roberts was invited by trumpeter Wynton Marsalis to join his band in the mid-’80s, playing on such Grammy Award-winning albums as J Mood and Marsalis Standard Time, Vol. 1. Six years of touring with Marsalis followed, establishing Roberts as one of the vanguards of young American jazz pianists. Roberts formed his own trio in 1993, and since then he’s been indefatigably presenting his interpretive style around the world as a musician, recording artist and assistant professor of jazz studies at Florida State University.

This week finds the Marcus Roberts Trio, with Rodney Jordan on bass and NEA Jazz Master/Wynton’s little brother Jason Marsalis on drums, in a weeklong residency at New York’s Jazz at Lincoln Center. I spoke with Roberts about his discovery of jazz, the role of technology in his life as a musician, and his thoughts on working with legends like Marsalis and Seiji Ozawa.

What can fans expect from your upcoming shows in New York?

They can expect sort of a wide range of what we like to choose from our repertoire—we have a pretty broad repertoire. We play standard tunes of [George] Gershwin and Cole Porter; we play blues by [Thelonious] Monk and [Duke] Ellington; we play [John] Coltrane’s music; we have a lot of original music that we play; and Jelly Roll Morton. It’s going to be a little bit freer this week, you know. We’re just going to look through the book and pick kind of a historical tour of jazz, if you will.

What was your introduction to jazz?

I grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, and I first started playing piano in church. I was self taught for four years, from eight to 12, and then at 12 I was listening to the radio and I happened to hear Duke Ellington. And I just remember being really enamored with his touch; his style; the chords he was playing. And it went from there; I went from Duke to Louis Armstrong and then I ventured to Miles Davis and Coltrane and Monk, and one by one as the years went on, I got more deep in being interested in how these guys were playing all this stuff that they were coming up with, and how I could emulate that.

Who was your first love in music?

Probably Duke Ellington; I think my real first interest was him. And also [jazz pianists] Teddy Wilson and Mary Lou Williams—I remember hearing Mary Lou Williams with Benny Goodman, and that always struck me. I guess when I’m listening to a great jazz artist, what I’m really always looking for is something that can be taken even outside of the context that they put it in, and I’m able to personalize it and identify my own personality and identity within it. So, honestly, there are many great artists that I love.

Growing up, how did you come to learn about Japan?

I don’t know—I think the first time I went to Japan was with Wynton in 1987, and then I believe went again with a quartet in ’89. But my most memorable experiences of going to Japan have always been with the great conductor Seiji Ozawa. He invited me there a couple of times, and we’ve done Gershwin’s Concerto in F there a few times. It’s probably one of the highlights of my career, going there, doing that with him, because he’s such an innovator, such a great man, and he’s always been very interested in the relationship between how jazz and classical music can be collaborated together, and we always enjoyed working with him there in Japan.

What was it like performing with the maestro?

Oh, my God, absolutely incredible—he is just amazing. He knows that score inside and out, and his dedication to just greatness in general, he’s very infectious. And my band and the other musicians always knew that it was going to be a great performance, because he just wasn’t going to have it any other way. If he had the schedule for rehearsals, I’d talk to him, and by the time we got going, he’d been up since four o’clock in the morning studying scores, making sure that everything was going to be all right. So, he taught me a lot about how you put things on the stage and how you continue to push yourself to reach a real level of expertise and communication with an audience.

Do you enjoy traveling? Where are some of your favorite places around the world?

I enjoy traveling; it’s always fun. It’s always a blessing to be able to play to people and hopefully inspire them through the music you play to have a better day or just something they might be going through. For me, I pretty much will go anywhere, but I love Italy because of the food there, you know? I like going to New Orleans because of the food—I like a lot of places, but I can’t single out a whole bunch of them. I think it’s more about just the variety of the different cultures and the places you can go, because all those different localities have different things that they bring to you, and I guess, from my perspective, since every year we’re going to different places, I guess I’m more intrigued with the act of traveling itself, wherever it is. I also like France for the desserts, and Japan for the sushi. [Laughs]

Click here for the rest of the interview.

Justin’s Japan: Interview with NEA Jazz Master Hubert Laws

By JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his NY Japanese Culture page here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

With a career in music that began in the 1960s, Grammy-nominated flautist Hubert Laws’ latest honor is the NEA Jazz Master Award, which since 1982 is the highest prize the U.S. bestows upon living jazz musicians.

Laws will appear at a free panel discussion with the other 2011 NEA Jazz Masters at New York’s Jazz at Lincoln Center on Jan. 10. (Doors open at 12:45 p.m., and a live video stream can be seen here.) The following night, he will perform at the annual NEA Jazz Masters Awards Ceremony and Concert. For those who can’t attend the sold out show, there will be a live video stream on the NEA website along with a simulcast on the Newark-based WBGO Jazz 88.3 FM and their site, and Sirius/XM Satellite Radio’s Real Jazz Channel 70.

This year also marks the artist’s 40th anniversary of his first trip to Japan. I spoke with him about his time there along with some of his other personal highlights as a musician.

Congratulations on your NEA Jazz Master award. How does it feel to receive this honor?

After learning of its significance, it is a humbling experience to be named among other respected artists of special accomplishment.

How did you find out that you won his award? Did you or anyone else campaign for it?

I happened to be on a tennis court playing doubles when my cell phone rang during a changeover. The gentleman asked if I had a moment—I said, “About 90 seconds.” When he announced the award, I said, “I think my partners will wait a little while longer.” I was not aware of this award, so could not “campaign” for it.

Tell us about your history playing in Japan and working with Japanese artists as a musician.

My first tour in Japan began in Tokyo in 1971 with the “CTI All-Stars” [Freddie Hubbard, Stanley Turrentine, George Benson, Grover Washington, Ron Carter, Bob James, Ester Philips, Hank Crawford and others].

We were greeted at Narita Airport by fans with banners and fanfare as though we were rock stars. That tour included several cities for about two weeks. Since then, 15 other trips there included my own group at the Blue Note Club, another with Ron Carter and his group, Chick Corea and his group, and Sonny Rollins with the Yomiuri Symphony Orchestra, where I premiered the Concertino for Flute and Orchestra by Harold Blanchard. This performance can be seen on the 30 Year Retrospective DVD; and excerpts can be seen on my website. The Laws family [Ronnie, Debra, Eloise and Hubert] appeared at the Cotton Club there in 2007. A JVC Jazz Festival was held there. where Eloise and I appeared there along with Nancy Wilson and others.

My most recent CD features Japanese child prodigy and pianist/keyboardist Yayoi Yoshida in flute adaptations of classical compositions: Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto #2 and Samuel Barbers’ Adagio for Strings. Excerpts also can be heard on my site.

Why do you think the Japanese enjoy jazz so much?

As a culture, it appears that the Japanese gravitate heavily toward education. This value seemingly leads to appreciation of substance. There is great “substance” in the art of improvised music commonly known as “Jazz.” As in any culture, the “foreign mystique” may also play a part. “A prophet is not unhonored except in his home territory and in his own house.” –Matthew 13:57, New World Translation of Holy Bible.

Click here for the rest of the interview.

See some familiar JET faces (including that of JetWit founder Steven Horowitz) in the latest issue of Shukan NY Seikatsu, a free, weekly Japanese newspaper available in New York. Along with Steven, JET alums Stacy Smith, Kia Cheleen, Tamar Entis, and Paul Benson sat down with the paper to talk about their experiences for a special New Year’s issue. The even was organized by Jon Hills, founder of Hills Learning (and husband of JET alum Kendall Murano).

The group was asked about what they learned from Japan, what they loved about their areas, what they thought was cool about Japan, and what their reactions were to some of the criticisms Japanese teachers have of JETs. The resulting “NY Cool” feature is front page news, with the full length article inside.

Read the full issue online here (the JET profiles are on page 4 and 5):

http://viewer.nyseikatsu.com/viewer/index.html?editionID=331&directory=../editions&page=1

For more background on the write-up, see this previous JetWit post.

Happy reading!

-Gail Meadows

Associate Editor, JetWit

Justin’s Japan: Interview with NEA Jazz Master David Liebman

2011 NEA Jazz Master Dave Liebman. (Marek Lazarski, courtesy of the National Endowment for the Arts)

By JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his NY Japanese Culture page here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

Brooklyn-born saxophonist and flautist Dave Liebman is one of this year’s recipients of the NEA Jazz Master Award, which since 1982 is the highest honor the United States bestows upon living jazz musicians. Liebman is best known for his work with the legendary trumpeter Miles Davis, joining his band in 1973 for a 16-month stint and playing on two studio albums, the final ones that Davis would record for the rest of the decade, as well as several live bootleg concerts that are available.

Liebman will appear at a free panel discussion with the other 2011 NEA Jazz Mastersat New York’s Jazz at Lincoln Centeron Jan. 10. (Doors open at 12:45 p.m.)The following night, he will perform at the annual NEA Jazz Masters Awards Ceremony and Concert. For those who can’t attend the sold out show, therewill be a live broadcast on the Newark-based WBGO Jazz 88.3 FM and their website, and Sirius/XM Satellite Radio’s Real Jazz Channel 70. I spoke with the artist about his thoughts on winning this award, his history in Japan, and his intriguing relationship with Miles.

How is one picked to be an NEA Jazz Master?

This is a very good question, which I hope to find out at the ceremony [laughs]…I think past inductees are a part of it—I have no idea. I can’t wait to know, assuming they will tell me the process.

Did you have to campaign for it?

Absolutely not; this was a phone call that came out of nowhere. I think my boss at the Manhattan School of Music, Justin DiCioccio, said he recommended [me], but the truth is, if you go to the site right now, you can put yourself in…the public is free to nominate anybody on the website. So that’s all I know about the process. How it goes from there to deciding [the inductees], I don’t really know, and I’m curious to find out.

You’ve played with Japanese artists and appeared on their albums since the early ’70s. How did that come about, and what were your impressions from visiting Japan through the years?

Of course, I had a lot of action in the ’70s and into the ’80s, but not so much in the last 10 to 15 years. First of all, the Japanese audience at that time was fantastic, and of course Miles Davis was a gigantic hero. The fact that I was with Miles put me right away into a special arena, and sure enough as soon as I got there I recorded. When I was on my first tour with Miles in Japan—it was the only time I went with Miles to Japan—I recorded my first record as a leader [First Visit, with Jack DeJohnette, Richie Beirach and Dave Holland], because Stan Getz’s group was there and the rhythm section was ready to go. I recorded with Abbey Lincoln also that week. In those days, when you went to Japan somehow you ended up with record dates. They were very, very enthusiastic, and business was good.

And then I had, of course, a long-term relationship with Terumasa Hino, the trumpet player, and drummer Motohiko, his brother who passed away a few years ago. I worked many times with the Hinos in Japan at a lot of festivals. Most notably there were two big concerts that I did in the ’80s—one for John Coltrane with Wayne Shorter and then in the ’90s with Michael Brecker, again for Trane ten years later. But as I said, not so much in the last ten to fifteen years. It was fascinating how deep the Japanese audience got into the music and how enthusiastic they were. But it seems to have faded, from what I understand. This generation is not as interested as before. So I can’t speak about the present jazz situation there, but I certainly enjoyed my visits.

Why do you think the Japanese had such an interest and enthusiasm for jazz?

I don’t know. I think they were fascinated by anything American, first of all. They probably loved Dolly Parton, or Sting, or whomever. I think they really liked Western culture. They were fairly prosperous during that period and when prosperity comes, people have more time to do leisure activities, enjoy culture and arts and so forth.

I think the Japanese temperament in general, the arts of Japan—everything from the sword stuff to the tea ceremony to the kimonos to the shakuhachi—they’re a really high class, sophisticated culture; that’s part of their being. And jazz, being as sophisticated as it is appealed to them. I think that’s part of what made them like it more than other cultures in Asia for example. I don’t see China—although we don’t know yet—embracing it the way Japan did, just from the difference of their M.O., the way they are as people. Japan is culturally kind of like the equivalent in Europe of the Germans, who are also very musically sophisticated and are really the best audience to play for as far as educated goes.

When was the last you played in Japan?

I think 2004 or ’05, we did a festival in Kyoto celebrating the history of the city; it was a special festival and I played with my regular working group of the last twenty years. I think that was the last time. You know, in general they just really appreciate art.

Read the rest of the interview here.

Justin’s Japan: Interview with Video Games Live Icon Tommy Tallarico

See Tommy Tallarico with Video Games Live at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark Dec. 29 and 30. (Videogameslive.com)

By JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his NY Japanese Culture page here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

Tommy Tallarico is the co-founder and CEO of Video Games Live, a touring showcase that for over five years has combined the excitement of a rock concert with the power of a symphonic orchestra featuring the music of the some of the most memorable video games in history. As the show’s lead guitarist, Tallarico is also the producer of the Video Games Live: Level 2 Blu-ray and soundtrack album, which made history last October by landing on Billboard’s Classical Crossover chart and earning a Grammy nomination for the Civilization IV song “Baba Yetu,” the first video game song ever to be nominated. I spoke with Tallarico prior to VGL’s upcoming shows this week at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, which will feature special guest performances by legendary female Japanese composer Kinuyo Yamashita (Castlevania).

This year’s VGL tour played around the world to new countries and fans. What were the biggest similarities and differences that you noticed among the crowds and the overall reception you received?

Each country we go to is different. They love different games; they play their favorite different systems. For example, when you’re paying in Japan, World of Warcraft isn’t really popular over there, because there’s not a lot of PC gaming. But when you play in China, World of Wacraft is like the biggest thing ever of all time. [laughs] So, crowds react to different things, and it’s always my challenge to create a set list and find out what the local gamers love and are into. But when you go to places like China and Taiwan and, most specifically, Brazil, the folks down there go absolutely nuts. I mean, they lose their minds. They’re so passionate and so appreciative that something like this exists and would come to their countries. It really shows.

Were there any things that really surprised you when visiting and performing in these new countries?

When we played to over 100,000 people in Taipei in one show, and we showed up at the airport, there’s literally hundreds of people there with signs greeting us at the airport and everything. That was pretty surprising.

Tell us about VGL’s Japan debut at Tokyo International Hall last fall. Which of your idols were you most excited about meeting and working with?

I had worked with everybody before the show, but what was really special about that show was the Koji Kondo performance. Of course, Koji Kondo is the composer of Mario and Zelda. This was the very first time, believe it or not, that Koji Kondo actually performed live in Japan at a video game covert. I found that to be unbelievable, so that was very special. Having both of the women who composed the Castlevania music there on stage was also pretty special as well, but I’d have to say that providing Koji Kondo with his first ever live performance in his home country of Japan was unbelievable. He played a solo piano piece of Mario, and he went into Mario Galaxy as well. It was really incredible.

Each VGL concert is performed by a local orchestra and professional musicians. Besides special guest appearances, are there any twists depending on where you play, or do the musicians understand what you’re trying to express as easily in places like Portugal and Poland as they do in the U.S.?

I think it’s more age delineated as opposed to area. Any young person in the orchestra—and when I say young, I’m talking maybe 45 and under—any young person in the orchestra for the most part knows a lot of the material, is really happy, and they understand it; they know what’s going on. And then some of the older people in the orchestra—not all, but there’s a smaller percentage of people, no matter what country we go to—they’re a little apprehensive at first; they don’t quite understand [it], playing this music that they’ve never heard, yet thousands of young people are screaming and cheering and clapping like it’s the second coming of Elvis Presley or the Beatles or something. And so, they’re confused by the end of it: “What’s all this stuff? World of Warcraft? Sonic the Hedgehog? This isn’t Stravinsky!”

These are classically trained musicians, but once they see the reaction of the crowd and hear the music and how it is, you know, legitimate music, they have a greater understanding and appreciation for video game music. So, what starts out maybe for some of the older, traditional people as apprehension at the beginning of the day, turns into adoration by the end of it. I’ll get people coming up to me during the intermission, and they’ll say, “I’ve been playing the oboe for over 40 years, and I’ve never heard a crowd response like this. When are you guys coming back?” [laughs] So, it’s pretty cool to be able to give that to them.

As musical director, do you always do a full run-through with the orchestra prior to every night’s performance?

For sure. We also send the musicians the music months ahead of time.

When the show was performed in Brazil, it was subsidized by the government for getting young people involved in the arts. How did you arrange that, and what was the public’s reaction to that performance?

It was something that the promoters down in Brazil and myself worked on with the ministry of culture down there, and this is our fifth year back—it was our fifth year in a row down there. It’s something that I wish more governments could see the benefit of this, because we’re looking at tons of people and e-mails or people talking to us at the meet and greet, who all say things like, we brought our daughter to the show last night and we were all sitting around the breakfast table this morning and my daughter said, “Mom, I’d like to start taking violin lessons so I can learn the music to Zelda” or Kingdom Hearts or Final Fantasy or whatever, you know. So those are real stories, and, again, the Brazilian ministry of culture is fantastic to realize that and to say we want young people to be interested in the arts and culture, and what better way than to give them a presentation of something that they know and love and enjoy, and are passionate about. I wish other countries did that; I wish our country did that! [laughs]

Click here for the rest of the interview.

Justin’s Japan: Interview with Filmmaker Amy Guggenheim on ‘When Night Turns to Day’

By JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his NY Japanese Culture page here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

New York-based writer/director/producer Amy Guggenheim is currently hard at work on When Night Turns to Day, a dramatic feature that will be shot in New York and Tokyo. A present-day romantic thriller with martial arts, sword choreography and tattoos, the film follows May, a young American female writer who gets drawn into both Japanese sword fighting (kendo) and a passionate relationship with Toshi, a young Japanese martial artist. Beyond anything she’d ever imagined, both must face secrets from their past, barely escaping with their lives.

Guggenheim herself is a third dan (degree) kendo practitioner who has competed in Tokyo, a grant recipient from the New York State Council on the Arts and the Mellon Fund, and the director of her own production company. I caught up with her to learn more about When Night Turns to Day, which begins shooting in Japan next year.

What made you interested in making a movie about kendo from an American perspective?

I got interested in making a film involving kendo after making a multimedia theater piece called Monsters and Marvels with video projection and 14 actors. It’s about the unconscious influence we have on each other from various cultures, Japanese being one of them. It’s also a way to express my vision of kendo as an American woman in 2010, interested in the “art” aspect of the “martial art.”

What is your personal history with Japan?

I’ve been involved with Japan in one way or another since the 7th grade. I was first interested in the design culture and the values of simplicity and essence, then later in kabuki, noh and butoh. In my background in theater, I was trained by Zen-influenced artists including Elaine Summers— an early intermedia artist from Judson Church (John Cage, Merce Cunningham, etc.), and then Eiko and Koma—butoh artists based in New York. When I was doing my own solo theater performance work, I started practicing kendo. For a few years I toured in Europe, Latin America and the U.S. performing my work and then practicing kendo with local dojos.

With the honor of having an Asian Cultural Council Grant in 2008, I was able to travel again to Japan (the first two trips were kendo-related—2006 participating in the first International Women’s Kendo Tournament in Tokyo), and in these last two years I’ve gone back several times and have been working with Masaru Koibuichi of Koi Pictures (our co-producer there), Setsu Asakura (art director) and others.

The dark, erotic tension of Japanese culture is my own language as well, and also the intuitive intelligence at the heart of kendo is my subject, too.

How did you get into kendo originally? Are there any films that cover the subject that inspired you with the idea or development of your film?

Bobby Troka, a kendo player and voice coach, worked with me on a solo piece of mine, suggesting I try it. I thought it was “too formal,” but once I did it, I fell in love with it and couldn’t stop! That was in 1990. There’s surprisingly few films that adequately deal with kendo, and I must say the idea developed out of my own experience and imagination and was inspired by people I met in the kendo world along the way. The way Kwaidan, directed by Masaki Kobayashi, deals with the uncertain spaces of the psyche, is evocative. Kurosawa’s Ran, Dreams and The Seven Samurai, Shindo’s Onibaba, Masumura’s Irezumi and Hong Kong martial arts films also have great inspirational material.

What are your current goals regarding the next steps in getting the film made?

We are assembling a terrific, experienced, creative team here and in Japan, and launched a mini-fundraising campaign going with Kickstarter.com that ran through November. We will next move on to preliminary test shooting and start working with sword choreographer Kataoka Noboru and actors in New York City. We are working hard to complete financing for the feature to shoot next fall, which will include investors, pre-sales and sponsors. If people are interested in donating to the project to help get us to principal photography next year, please go to our website at www.whennightturnstoday.com. You can also contact me by e-mail about donations, the project, or interest in getting involved with creative skills or production.

Click here for the rest of the interview.

National AJET’s “Life After JET”: Teaching English in Japan – Lucas Clarkson

National AJET shares former JET participants’ experiences – and a little advice – with current JETs in their new monthly interview, Life After JET. Contact lifeafterjet [at] ajet.net to be featured in future posts.

*************

Lucas Clarkson spent five years on JET as an ALT at high schools and elementary schools and now teaches at a private school in Yokohama. He is currently a social studies instructor at the International Baccalaureate (IB) Middle Years Programme (MYP) at Chuo University Yokohama Yamate Girl’s School. Lucas told us a little more about his transition from JET to another teaching position in Japan for this month’s “Life After JET.”

National AJET: Why did you decide to continue teaching in Japan after JET? Was that always your plan?

Lucas Clarkson: I figured that I had so much invested in this country in terms of time spent, friendships made, and language (presumably) acquired, that to leave after JET would be a mistake. I always knew that I wanted to teach in some capacity, and I was lucky enough to find the position I did, when I did.

National AJET: Are there any resources you could recommend to someone looking for a teaching job in Japan?

Lucas: As far as resources go, there are the usual suspects: GaijinPot, Ohayo Sensei and Jobs in Japan. These are all helpful if you know exactly what you’re looking for. If you’re looking for International School positions there are a number of online headhunter-type sites where you pay a nominal fee to post your resume and other information online for prospective schools to see.

National AJET: Can you tell me a little bit about the logistics of staying on after JET – moving, getting a new visa, etc? Where there any difficulties that you didn’t expect?

Lucas: No major difficulties at all really, as long as you have a legitimate employer willing to sponsor you. If you decide to take the independent route however, you’re going to run into a host of difficulties. Just be sure to have (a) Japanese friend(s) on hand to help you with visa paperwork and the like.

Click here for the rest of the interview.

Justin’s Japan: Interview with ‘Fried Chicken and Sushi’ Cartoonist/JET Alum Khalid Birdsong: Part 1 of 2

By JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his NY Japanese Culture page here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

Cartoonist/JET alum Khalid Birdsong. (Courtesy of K. Birdsong)

Cartoonist and teacher Khalid Birdsong lived in Japan for two years working as an assistant English teacher on the JET Program. Last spring he launched the original webcomic Fried Chicken and Sushi, which is published twice a week and based loosely on his real-life experiences in Japan, mining the cross-cultural humor that living abroad provides.

Birdsong now lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with his wife, whom he met in Japan, and baby daughter. He plans to visit Japan next year, which he feels will inspire even more stories. I spoke with the artist about his time on JET, life as a teacher, and the future of his creation.

Where did you grow up, and what is your history with comics?

I guess I’d call Atlanta, Georgia, home—that’s where I’ve spent most of my life. I’ve traveled quite a bit. I’ve lived in several countries—in Nigeria, Germany, the Bahamas and also Japan. So I’ve kind of had that international view of things. I’ve always enjoyed reading comics no matter where I might be living. I’ve always liked to draw them, but I didn’t really read American comics until I was in middle school. Mainly, I would read Asterix and the European comics, and I’d watch a lot of animation. But I’d still draw my own comics and make up my own characters and do my own comic books and then sell them for a quarter to my friends; people always knew me as the comic book kid. So I just kept it going—even in college, I went to Howard University in Washington, D.C., and I studied graphic design and illustration there. Everything I learned, I tried to bring it back into comics and cartooning. I also did T-shirt designs, and did some freelancing for a couple of years on my own, which meant that I was freelance working, but I was also a security guard, and I was waiting tables, and all the other things that you do. And I just fell into teaching art in elementary school, and I’ve been teaching ever since. I really, really love it. It’s great.

How did you get hooked on Japanese culture?

I think like most people in high school, at least when I was in high school in the early ’90s, it was this brand new thing, when trying to look at Japanese animation when you didn’t have a translation and watching stuff you couldn’t understand with friends—and trying to read any certain comics that you could get your hands on—it was something new and exciting. I just always thought, “Boy, it must be interesting to actually live in Japan; that must be something amazing to do.” But I never thought I would really ever do it. I was just interested in the art and language. Even in college, same thing—it became more prevalent. I would enjoy more and more anime and manga, along with American comics. So I think that’s what really started me off. I was drawing comics, but I was still drawing in an American-type cartoony style. I didn’t have that quote-unquote manga style, but that’s what kind of started me into it. And then I started thinking what it would be like to live over there once I started actually teaching art.

That’s when you discovered the JET Program?

Yeah, when I was teaching art, I guess I had this feeling—I was in my mid-20s, and I just thought it would be nice. Me and my friend Jason, who’s actually the J in the Fried Chicken and Sushi comic—we both talked about going to Japan just to visit just for a couple of weeks. And so we tried to plan a trip, but we didn’t have the money and all this—didn’t quite happen. And then, he actually found out about the JET Program online, and then I looked into it, too, and we said, “We should try to apply, let’s do it.” I was already teaching [in the U.S.], so we applied, and I went through the, whatever, nine-month span of time that it takes to go through everything, and I made it in and he didn’t, and it really was not cool; it really hurt us both. But he’s a good friend, so he said, “You need to go on ahead and do it,” and so I did.

So the relationship between the two characters in the comic is based on real life.

It is. A lot of what I’m telling in the comic is based on truth in my life, but there are things that I may change or over exaggerate or add on as time goes by, as Karl’s character develops and becomes more of his own character and individual, and the same with J. So there’ll be things that I make up, but I try to keep as much of it as I can based on some of my real experiences—I think people can tell what comes from truth and real experience.

So you’re saying you didn’t have a talking tanuki spirit haunting you?

[laughs] That’s great! You know, the thing with that is, in real life I really do have a very overactive imagination. You might have known some Japanese when you went over there, but for me, I really didn’t. I listened to some CDs and studied some basic greetings and everything, so when I was there I had no idea what anyone was saying. I would just get lost in my own imagination, and there were tons of stories going on in my head and all this—I would imagine things moving around that weren’t moving around. So no, I didn’t have a tanuki, but I wanted to have something that would represent that state of craziness I was in, where I’m there but also kind of detached from it all.

Because of budget woes, there’s been talk of the Japanese government trimming or potentially cutting the JET Program altogether. As a JET alum, what are your thoughts on the value and benefits of the program from your own experiences?

I think that for me, it was great to be able to travel to another country and to get international experience as a teacher and teach English and be able to travel in a place where I never thought I would and learn a new language, so that is very valuable for me. I think that even though people argue, saying that maybe having a native speaker in the classroom is not that all that important for Japanese people, I think that it’s still great for them to have someone from another country, because I feel that Japanese people don’t really get a chance to really experience or talk to or have someone that’s not Japanese around them typically. So I think it’s a great way for them to not just learn about other cultures and what’s around them, not to mention English, but in terms of international relations I think it’s a really great program for that.

And the work you’re doing now is an extension of those ideals.

I totally agree, it’s really great. It challenges stereotypes, and I wish we could have more of it instead of cutting it down.

Click here for the rest of the interview.

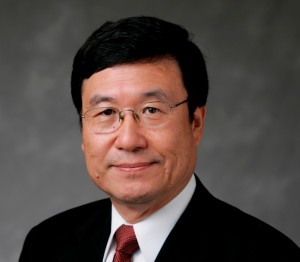

Justin’s Japan: Interview with author Hideo Dan on ‘Lipstick Building’

- Meet ‘Lipstick Building’ author Hideo Dan at Manhattan’s Kinokuniya Bookstore Saturday, Dec. 11. (Courtesy of Hideo Dan)

By JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his NY Japanese Culture page here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

Hideo Dan is a vice president and attorney at law of a New Jersey-based healthcare company who is now a debut author. Published by NY Seikatsu Press, Lipstick Building is a fast-paced suspense novel based on the author’s 30-year real-life experience in New York as a shosha (trading company) man and a corporate attorney with an international law firm.

Kenji Kadota, who works for a Japanese trading company in New York, is introduced at a party to Suzanna, a beautiful businesswoman from Peru. She proposes a big business opportunity to Kenji—an attractive prospect of exporting Japanese machinery to a major Peruvian construction company. Is this a great business chance, or is something ominous ahead? The story develops quickly into intrigue and adventure, with Kenji and Suzanna crisscrossing through South America and Europe, providing readers entertainment and thrills to the end.

The author will be the subject of a special talk and book signing event Saturday, Dec. 11 at Manhattan’s Kinokuniya Bookstore. I caught up with him to learn more.

How did you come to the U.S.?

The first time I came to the U.S. was in 1971, when I attended Indiana University for a year to study journalism. I could not land a job in journalism, so I started to work for Nissho-Iwai, a trading company, a.k.a. shosha, upon graduation from Osaka University with a law degree. In 1979, Nissho-Iwai sent me to its New York subsidiary as legal manager.

Lipstick Building is based on your three decades of experience at a Japanese trading company. How long did it take to write this book?

Actually, I was with the trading company for 14 years, seven years each for Japan and New York. After that, I left the company and joined a law firm in New York, having had passed the New York Bar Exam while I was with Nissho-iwai American Corporation. After almost nine years with the law firm, I joined Eisai, a Tokyo-based pharmaceutical company, as general counsel for its U.S. operations.

It took nearly one and a half years to write this book. I was able to do it since I was asked to manage Eisai USA Foundation, a charitable organization on the part-time basis, two years ago.

What is your personal experience with Peru? Are there any other international experiences that helped your writing?

Unfortunately, I have never been to Peru—I was planning to do so this year but because of the flood at Machu Picchu, my trip was cancelled. So I did lots of research on Peru on Google and at a library. I had met a very attractive Peruvian student when I was attending Indiana University, which gave me some inspirations for this book. In fact, Europe (Spain and Switzerland) plays a much larger part in this story than Peru. I have been to Spain and Switzerland on business and pleasure on numerous occasions and have been attracted by culture and scenery in those countries. Especially in Spain—I was fascinated by flamenco and its dancers. Flamenco is an important element in this novel.

What are the big differences between working at a trading company in Japan versus the U.S.? Did these differences shape the story?

At the trading company in New York and also at the law firm where I worked, naturally I interacted heavily with non-Japanese people, colleagues and clients, which constantly reminded me of cultural and linguistic differences between Japan, the U.S. and many other different cultures. As someone who is very curious about anything, I enjoyed learning those differences on daily basis. At the same time, I got impressed with striking similarities at a deep human level. My book certainly reflects those experiences and observations.

Click here for the rest of the interview.

Justin’s Japan: Interview with ‘Tonoharu’ Cartoonist/JET Alum Lars Martinson

By JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his NY Japanese Culture page here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

Minnesota-based cartoonist Lars Martinson went to Japan in 2003 to teach English on the JET Program, an exchange initiative sponsored by the Japanese government. During his three-year stay in rural Fukuoka, he was inspired to break ground on an ambitiously stylized four-part graphic novel named Tonoharu (Pliant Press) based on the trials and tribulations of living in Japan. Part Two was released in November, and I caught up with the artist to discuss the series so far and Japanese life through an expat’s eyes.

How would you describe the differences in Tonoharu: Part Two compared to the previous book? Did you do anything different in terms of storytelling or approach?

With each volume I’ve tried to explore different facets of living abroad. The first book focuses on the sense of loneliness and isolation that occurs after the “honeymoon period” of cultural acclimation ends. The second book deals with the relationships that develop, both with members of the native population and with other expats.

My approach to storytelling has gotten more deliberate as I’ve gone along. For Tonoharu: Part One, I started by writing “Page 1, Scene 1” at the top of a piece of paper and launching into a detailed script before I had a clear sense of what direction I wanted the story to go in. Diving straight into minutiae like that is like working on the interior design of a house that hasn’t been built yet; you should know how big the windows are before you pick out the curtains. So for Part Two—and now Part Three—I’ve given much more thought to the structure of the story, and made sure I was happy with the big picture before I got too wrapped up in details and nuance.

Tell us about your experiences on the JET Program. What made you choose to apply, and what was your overall take on the three years that you were there for?

When I was 16, I lived with a host family in Nagoya for a summer vacation exchange. The experience inspired a lifelong interest in international travel. I’d go on to live in Thailand and Norway for a year apiece as an exchange student, and visit a dozen or so other countries as a tourist. After I graduated from college, I wanted to try working abroad, and also wanted to return to Japan. A friend of mine introduced me to the JET Program, and I knew immediately that it was right for me. And sure enough, my three years in the JET Program were among the best I’ve ever had.

All JET participants hit high and low points while in Japan. What were some of yours?

My elementary school classes were among the most satisfying experiences. I planned all the lessons pretty much single-handedly, so once I got the hang of it, it was gratifying to see how excited the kids were about learning English, and how much they retained.

One of the more frustrating aspects of the experience, at least in the beginning, was the language barrier. It’s hard to form meaningful friendships when you can’t—y’know—talk to people. So it was always sad when I wanted to befriend someone and they clearly wanted to befriend me, but the logistics of not being able to communicate effectively got in the way.

Last summer, it was announced that the JET Program is facing sweeping budget cuts that may endanger its future. What’s your take on the value of the program in today in Japan and in the participants’ home countries?

I suppose with the economy being what it is, some cuts are probably inevitable. But I really hope they don’t gut the JET Program. My life has been enhanced beyond measure by having the opportunity to interact with foreign cultures, and I hope Japanese students will continue to be given the same opportunity. It’s hard to quantify the benefits of the JET Program, but that doesn’t really make them any less real or important.

What kind of feedback on the books have your received from JETs and those associated with the Japanese community?

I’ve tried to make the book accessible to readers regardless of their background, but it goes without saying that those who are familiar with Japan or the JET Program are able to appreciate it on a different level. JETs tend to pick up on all these little details in the books that other readers breeze pass without notice. I remember a JET alum commenting on a scene in Part One where the main character wears a fancy suit to his first day on the job, but since it’s summer vacation everyone else in the teacher’s room is wearing ratty gym clothes. It’s little things like that that you’d only consciously notice if you’d been in that situation yourself.

Click here for the rest of the interview.

Justin’s Japan: Interview with ‘Hiroshima in the Morning’ Author Rahna Reiko Rizzuto

By JQ magazine’s Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) for Examiner.com. Visit his NY Japanese Culture page here to subscribe for free alerts on newly published stories.

In June 2001, award-winning Japanese American author Rahna Reiko Rizzuto went to Hiroshima on a six-month fellowship to interview the hibakusha, or remaining survivors of the atomic bomb. Three months later, the September 11 attacks on the U.S. changed everything, from the recollections of the survivors to Rizzuto’s own relationship with her family back in America, including her husband and two young sons in New York.

The result was Hiroshima in the Morning, a memoir released last fall in which the author weaves these threads into a deeply personal story of awakening about how we choose our identities, how we view history, and how we use memory as a story we tell ourselves to explain who we are. I caught up with Rizzuto to discuss her emotional journey and impressions of Japan.

What was the most interesting thing about talking with the atomic bomb survivors in Hiroshima?

I went to Hiroshima initially because I knew so little—almost nothing—about the atomic bomb and its effects. I arrived more than 55 years after the bombing, so I expected memories to be a little hazy. When I first arrived, I met people who were very committed to telling their stories in the interest of peace. They wanted to testify about the power of the atomic bomb and the devastation of war in general in hopes that there would be no more war. That would make their sacrifices worth it.

I was there to write a novel, though, not a factual piece, so what I was looking for was textures and details about what it was like to live in those times, and how one survived war. So what I was getting was not exactly what I was looking for. Their stories were very complete and rehearsed. What happened then, though, was after three months of listening to these testimonies, the September 11th attacks happened within sight of my Brooklyn home. The world changed. And so did their stories.

In hindsight, how different did the interview project turn out because of 9/11?

I don’t think anyone can underestimate the effects of those attacks. They reverberated immediately, all the way to Japan, and we all suddenly felt the world was not safe. We were not safe. And if we weren’t safe, there was no peace, and if there was no peace, the hibakusha realized, then their sacrifice was for nothing.

Almost immediately, this destabilization affected their stories. They began to feel more, and to remember more. Moments and people they had blocked out came back to them. They remembered heat, and color and sound. And they remembered what it felt like to go back to their homes and find their mothers’ bones.

Which of the testimonials affected you the most? Why?

The most unbearable stories were often about children. Children who died; children who tried to save their brothers or parents; children who cremated their parents, at age six, because that was what their parents would have wanted. In the months after 9/11, though, something happened which was very moving and powerful. A number of people came to me to tell their stories. Before then, I had been finding my own interviewees with the help of my translators, but after September 11th, I found out that many people actually knew I was there, listening, and they sought me out because they needed a witness. They needed a safe place to relive, and purge, their memories. And then, it wasn’t just the sad moments. It was also the happy memories of life before, and their family members before. They needed to share those, too, and they gave them to me so their loved ones would not fade away.

Click here for the rest of the interview.