“By dramatizing some of the people who were on the receiving end of that racial hatred, I think the book might give a concrete sense of what American power can do when it is unleashed against people in other parts of the world. I hope the experiences of Jiro and Mitsuko make readers think twice about that.” (Louis Templado)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio has had experience working at Ishikawa Prefecture’s New York office while seeking opportunities with publications in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and comic books on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

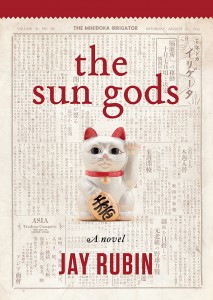

A Professor Emeritus of Harvard University, Jay Rubin has also served as a distinguished translator of Japanese literature for more than a quarter century, most notably on the works of Haruki Murakami. June 2 marks the release of his debut novel The Sun Gods (Chin Music Press), which is set in Seattle during World War II and explores the relationships between a Seattle-based Japanese national named Mitsuko and her young adopted American toddler, Billy, who are both interned by the U.S. government at the beginning of the war. Years later, Billy begins a journey to newly reconstructed Japan to find his Japanese mother and learn the truth about their shared past.

As part of the book’s launch, Rubin will be making live appearances from coast to coast, starting with Japan Society in New York on May 7 for an event titled The Magical Art of Translation: From Haruki Murakami to Japan’s Latest Storytellers, featuring other guest authors and moderated by JET alum Roland Kelts (Osaka-shi, 1998-99).

In this exclusive interview, Rubin shares with JQ the legacy of the war on his own writing, the attention to historical detail that went into The Sun Gods (with a few liberties taken), and what makes translating Japanese such a liberating experience.

JQ magazine readers are primarily JETs, JET alumni, and others who have worked and resided in Japan or have a strong interest in the country. Could you tell us about what inspired you to study Japanese language and culture and about any time you spent living in Japan?

In my second year at the University of Chicago, I was going to take one course on something non-Western for the fun of it, and one of the courses that happened to be available was an introduction to Japanese literature (in English translation, of course). I was so fascinated by the literature and by the professor’s remarks on the original language that I immediately started studying that language. I sometimes wonder what would have happened if the course I stumbled into happened to be Chinese history. I spent four years studying the language in Chicago before going to the country itself on a Fulbright fellowship. My spoken Japanese was so bad, all I could say to the young woman bartender at the first bar I wandered into was, “Do you realize you just used the word ‘wake‘ (わけ) three times?” I studied in Tokyo for two years, often wish I had made it four. I’m still remarking on how many times people use wake in sentences. I studied mostly Meiji literature while I was in Tokyo, not Noh drama like The Sun Gods’ Bill, though Noh was a side interest, and I did a lot more work on it in later years.

To start off talking about The Sun Gods, how would you describe your new book to potential readers?

This may sound like ad copy, but I’m comfortable with the summary on the book’s front flap:

Opening in the stress-filled years before World War II, The Sun Gods brings together a white minister to a Seattle Japanese Christian church, his motherless young son, and a beautiful new arrival from Japan with a troubled past. The bombing of Pearl Harbor intrudes upon whatever happiness they might have had together, and the combination of race prejudice and war hysteria carry the action from Seattle to the Minidoka Internment Camp in Idaho. Nearly two decades later, the son is ready to graduate from college when memories of Minidoka and of his erstwhile Japanese mother begin to haunt him, and he embarks on a journey that will lead him from Seattle’s International District to war-ravaged Japan in his attempt to discover the truth about his past.

The internment of people of Japanese ancestry in America that occurred during World War II is rarely dwelled on as much as other events of the war, how would you explain the internment and the reasons it warrants further attention to someone unfamiliar with the topic? What is the most important message you hope to get across?

If there’s a “message,” it’s to convey a historical moment, central to which was the fact that our government established concentration camps within its borders in order to lock up members of a particular racial group, and that this was supported by both public opinion and the Supreme Court with no constitutional justification whatsoever. The government has since apologized openly and eloquently, thus making a repeat performance highly unlikely. Japanese-American organizations, it should be noted, were among the most outspoken against anti-Muslim racism following 9/11.

The Sun Gods is a compelling story that simultaneously explores the power of love in opposition to fear and hatred while also portraying a setting meant to convey historical fact. When you first undertook writing the book, did you feel one of these aspects was more important to achieve than the other? Were there times you felt that you had to compromise historical accuracy to create a compelling narrative or vice versa?

I like to think there were almost no compromises of historical accuracy. When the heroine leaves the camp to be repatriated, it happens on the actual day such people departed, and the ship she takes is the one actually used for such prisoner exchanges. The big bon-odori scene occurs on the night of August 21, 1943, which was the date of an actual bon-odori in Minidoka and the date of the page from the camp newspaper shown on the book’s cover. I’m more of a professor than a novelist, so there was always a possibility that pedantry might outweigh drama, but I was tremendously excited by the process of fitting my fictitious characters into a highly detailed historical framework. I can think of one inaccuracy, though. When Tom goes to see the Judy Garland movie Little Nelly Kelly, he does so several weeks before it actually played in Seattle’s Roosevelt Theater. I had to tinker with the chronology a bit in that part of the novel, and rather than try to find out which movie was actually playing at the Roosevelt that night, I liked the silly title so much that I decided to keep it.

I am curious to hear how much you put of yourself into one of the main characters, Bill Morton. In what ways did his interest in Japanese culture and his observations about Japanese people, religion, and culture during his first visit to Japan mirror your own?

Certainly his ignorance reflects my own. When he tells Frank he knows nothing about the relocation camps, it represents the moment I first learned about the camps from a professor in graduate school. I could hardly believe that such a thing had happened, and I could hardly believe that I had reached my mid-twenties knowing nothing about it. The long letter Bill writes to Frank from Tokyo contains a lot of my experiences, including his encounter with an old man who looks like the Meiji era novelist Nagai Kafu, but who turns out to have been a peanut vendor in Coney Island.

Much of the book takes place in Seattle, near where you live now. Did you also grow up in Seattle? How much has your time there influenced your writing?

I would never have written the book if I hadn’t moved to Seattle from the East Coast to begin teaching at the University of Washington. I had read several books about the camps after my professor told me about them, but I had never met people who had been sent to them, people for whom the experience was a painful living memory. In my mind, the character Frank Sano is named for Frank Miyamoto, a kind and funny man who spent part of the war in the Tule Lake relocation camp, who was the author of Social Solidarity Among the Japanese in Seattle cited in my note on sources, and who was a professor at the University of Washington and the husband of my children’s piano teacher. With people like that around, the milieu in Seattle was quite different, and the University of Washington had tons of material on the camps that I would never have found in the east. I was born in Washington, D.C., but I’ve lived in Seattle long enough to count as a native.

In your note on the sources used for the novel you wrote that the major characters and events were entirely fiction, but the setting for the story is authentic. One of the sources you use is in the Minidoka Irrigator, the newspaper published by the residents of the Minidoka Relocation Center which appears in the book. Why did you decide to use this source in particular? Were there any reasons to highlight Minidoka over other camps to feature in your novel? Were there similar sources drawn from other camps that weren’t as prominently featured in the story?

Some of the details come from accounts of other camps, but coming across the Irrigator in the University of Washington Library’s Special Collections, it was such a treasure trove of information, there was little doubt that this was going to be a Seattle story. Another important factual source was Monica Sone’s wonderful memoir, Nisei Daughter. One of my fictional characters lives in the actual Carrollton Hotel owned by Monica Sone’s father, and there are all kinds of other little hidden footnotes pointing to that book. Anyone with a fresh memory of Nisei Daughter can hear the echoes of it in The Sun Gods.

In the present day, Japan and America have a strong alliance despite their conflicts during World War II. While the war ended over fifty years ago, its memory remains an important part of international politics and policy to this day. In what way do you feel your book contributes to ongoing conversations about Japan and America in World War II and their relationship today?

Make that seventy years! Have you noticed all the publications and observances marking this anniversary? You know, when I was a kid, we still had John Wayne killing “Japs” in movies, and nobody thought twice about it (unless you were of Japanese ancestry). By dramatizing some of the people who were on the receiving end of that racial hatred, I think the book might give a concrete sense of what American power can do when it is unleashed against people in other parts of the world. I hope the experiences of Jiro and Mitsuko make readers think twice about that.

Most of the main characters come from a strong religious background, and throughout the story they experience crises of faith that lead them to reassess their belief in God, divinity in the world, and their purpose in it. The title alone speaks to the importance of these spiritual journeys. In a book already focusing on accurately depicting a setting and time in history while also telling a compelling family drama, what do you feel that these spiritual journeys contribute to the overall message and feeling of the novel?

At one point before Pearl Harbor has prompted the U.S. to enter the war, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes is quoted in the book as urging support for Britain in its battles by saying, “We should supply instruments of war to those who are fighting for our Christian civilization.” To me, this sounds like nothing so much as early calls for an American “crusade” against the forces of evil following 9/11. We are Americans, we are Christians, we are white, we are good—no matter what we do to assure the victory of our exceptional goodness, be it locking up yellow people, incinerating Dresden, torturing Islamic captives, or vaporizing two Japanese cities with a newfangled bomb. I think it’s pretty clear that all religions are superstitious combinations of wishful thinking and mass hysteria, but Christianity has a special capacity for this kind of hypocrisy. Once you are convinced you are good, you can get away with murder. The “spiritual journeys” you (Julio) point to tend to be in the direction of sloughing off this socially-induced self-satisfaction, of recognizing religious doctrine as “an illusory castle built on a foundation of empty words,” and coming to appreciate the innate holiness of everyday life.

If one of the characters you created were to come to life, which one would you want to meet and what would you want to say to them or ask them?

Mitsuko, without question. She was a revelation. I had often doubted novelists who spoke of their characters’ autonomy, but damn if she didn’t start saying and doing things I never anticipated for her. I remember walking along with my wife one day after a morning of writing when Mitsuko had surprised me by reacting to a crisis with surprising strength, and all I could say was, “What a woman! What a woman!” I know, it sounds crazy, but it actually happened.

Many of our readers will be familiar with your work translating Japanese novels, so I’d like to take the time to ask a few questions about that. Most recently you’ve translated Book One and Book Two of Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84 and several of his other books before that. How do you compare your writing process and style when you are translating to when you are penning your own story? Do you feel that your experience translating has significantly helped you write The Sun Gods? How do you compare your own approach to structuring a story to Murakami’s?

I can’t even begin to process this question: how could I presume to compare my “approach” with Murakami’s as if we’re both equally valid novelists? One thing I can say is that translating from Japanese is a lot like writing your own original prose because the expressions and grammatical structures of the two languages are so different. Translating from Spanish or French, I’m sure, is far more constraining because each word or phrase demands that you find something close to it in English. If you tried to do that with Japanese, you’d write nonsense. After I’ve read a Japanese sentence, I’ve got images in my brain that I have to find equivalents for in English, but the structure of the Japanese is no help at all in that search. It’s very liberating.

Which writers, in English or Japanese, inspire you? When you are not writing, what are you reading these days?

Before I got into Japanese literature, Dostoevsky and Beckett were the authors who spoke to me most directly, and since then it’s been Natsume Soseki and Murakami. I’ve been reading Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant, can’t quite explain its strange power. His strong moral sense is very British, not at all Japanese. Usually, though, after a morning of translating, my brain is fried, and I want to get out of the house, do anything but read. I tend to go for magazines—the New Yorker, the Nation, Opera News.

What advice do you have for those studying Japanese who aspire to translate literature in the future?

Sorry, but the best advice is to get a day job, one that doesn’t leave you too tired to concentrate on literary translation. Being an academic worked out well for me. The most important thing is to hone your tools—that is, keep writing and writing. The more you use your language, the more easily you can find ways to say exactly what you want to say. Oh, I guess what I’m saying here is that the writing of the English is more important than the reading of the Japanese. Of course, an accurate understanding of the Japanese text is important, but it’s just the starting point.

The Sun Gods will be released in June; could you tell us what’s next for you? Will you be doing any book signings or promotional events? Where can our readers follow your work in the future?

If it weren’t for all the excitement of having Chin Music Press bring out The Sun Gods, I’d be a lot farther along at compiling a book of Japanese stories for Penguin, but that will be my main project for the next couple of years. I’ve just finished revising my old translation of the Natsume Soseki novel The Miner for Aardvark Bureau. I think it’s coming out in the fall. It’s Soseki’s least popular novel, a weird, Beckett-like descent into the brain that is Murakami’s favorite Soseki; he wrote about it in Kafka on the Shore, and he’s written a terrific introduction for this new edition. My translation of Murakami’s interviews with conductor Seiji Ozawa will be coming out from Knopf next year. As for “following” my work–did I just write that? They made me get an Amazon author page, so that will probably be the best place. You can see a picture of me in my Uniqlo down jacket praying to the sun gods. I’ll be doing some readings in Seattle, San Francisco, and L.A. in May and June, and going to Tokyo in July in connection with the Japanese translation of The Sun Gods by Motoyuki Shibata and Shunsuke Hiratsuka coming from Shinchosha. The big Chin Music Press launch of the novel will take place at 7 o’clock p.m. on May 15 at Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle. Everyone’s invited.

For more on The Sun Gods, visit www.facebook.com/chinmusicpress. For more JQ magazine interviews, click here.

2 comments so far...

Great interview. I’m struggling to understand what Jay meant about using the word “wake” in Japanese? Does he mean the verb “okiru?” Or wake, as in わけ? Any context?

Great interview! I had Jay Rubin as a professor when I was an undergrad at Harvard. His class introduced me to the novels of Murakami Haruki.