JQ Magazine: Film Review — ‘The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness’

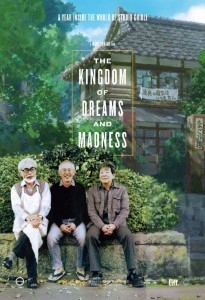

“Although beautiful and carefully crafted, in the end this work is one that ushers you into a new era of Ghibli by giving you a bittersweet goodbye.” (GKIDS/TIFF/© 2013 dwango)

By Alexis Agliano Sanborn (Shimane-ken, 2009-11) for JQ magazine. Alexis is a graduate student of Harvard University’s Regional Studies—East Asia (RSEA) program, and currently works as an executive associate at Asia Society in New York City.

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness is a documentary following animation director Hayao Miyazaki during his last months at Studio Ghibli. Centering on the production arc to The Wind Rises, Miyazaki’s final and most controversial film, it offers a unique glimpse into the fading days of Studio Ghibli with Miyazaki at the helm.

The film is directed by Mami Sunada, a former assistant director on Hirokazu Kore-eda’s films. Although the documentary does not detail the advent of the unprecedented behind-the-scenes access, from its beginning Sunada and Miyazaki share a tacit understanding that his film straddles a nebulous period. It is the beginning to the end of an era. As Miyazaki admits unreservedly, “I’m a man of the 20th century. I don’t want to live in the 21st.” This documentary captures his twilight world.

Fading though Studio Ghibli may be, it is still a place where one anticipates a world not beholden to reality. What one finds is an atmosphere entrenched in the daily slog. There are deadlines to be met, decisions to be made, marketing, budgeting, and finances that throw the project for a whirl. It is a work place like any other. Somewhat unromantic.

Yet, just like the Ghibli films themselves, this documentary captures the beauty of the everyday. It is there we find appreciation, meaning and relevance through details and rituals. For Miyazaki, these include greeting kindergarteners on their way to school, going up to the rooftop to “watch the sky,” or even the small cheerful doodles pinned about the office with inspirational messages. These simple elements stitch the work into something meaningful.

Vignettes aside, the documentary focuses on Miyazaki himself. We follow him around the studio, watch him work, listen to him grumble, ramble or deliberate. An animation “god” though he may be, this film unabashedly shows his foibles and follies: His rather callous and aloof nature, the way he speaks disparagingly or impatiently about certain individuals, or his morose and oftentimes bleak outlook that gets the better of him. At one point he states that “dreams are cursed by sorrow in a world that is mostly rubbish.” And maybe by his reckoning they are.

Yet despite his dark nature, there is an inextinguishable vivacity to him. If there was ever a workaholic, Miyazaki is certainly it. Yet unlike so many people nowadays who devote themselves unassumingly to a meaningless job, Miyazaki is a man who puts a part of himself into an effort to create something lasting and beautiful.

A Ghibli documentary, even one about the “last hurrah,” would not be complete without producer Toshio Suzuki, Miyazaki’s right-hand man. While Miyazaki is like a balloon soaring high above the clouds, Suzuki is the man who holds tight to the string. He has the nature of someone who has weathered many storms, and as such knows how to withstand the tempestuous and mercurial Miyazaki. More so than anyone, Suzuki seems prepared to face the future in stride. Watching him juggle responsibilities is one of the more interesting facets to the film.

Meanwhile, there is Isao Takahata, the animation director famed for such films as Grave of the Fireflies, Only Yesterday, and Whisper of the Heart. Takahata, some say, is the complement to Miyazaki; the light to the shadow or the shadow to the light. To the bitter end, their careers have been defined by a friendly rivalry. Spoken of yet unseen throughout the film, the dichotomy between the two directors only fuel the general atmosphere of disquiet. Featured on the film poster, Miyazaki, Suzuki and Takahata are the old-timers facing their greatest challenge: the end of their careers.

In the end, this film is subdued and melancholy. Had it been 15 or 20 or even 10 years prior, there may have been an atmosphere of immense energy. Those were the days of Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, and the opening of the Studio Ghibli Museum. Instead, with the studio transitioning to a new era, Sunada seems content to capture the day-to-day realities. There is little retrospection or insight to the past films; rather, only a thin period is covered.

Although beautiful and carefully crafted, in the end this work is one that ushers you into a new era of Ghibli by giving you a bittersweet goodbye.

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness opens today at IFC Center in New York City. For showtimes, click here.

For more JQ film reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.