“With wit and humor, Miyazaki offers insight from his long career with every turn of the page. Like an unforgettable sunset or the first time a cooking experiment came out well, he discusses experiences that leave you unexpectedly changed.” (VIZ Media)

By Alexis Agliano Sanborn (Shimane-ken, 2009-11) for JQ magazine. Alexis is a graduate of Harvard University’s Regional Studies—East Asia (RSEA) program, and currently works as an executive assistant at Asia Society in New York City.

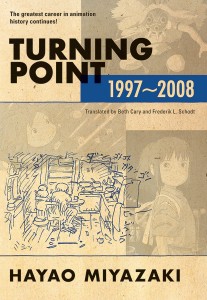

I consider myself an aficionado of director and animator Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli. Having seen his work countless times, visited the museum in Tokyo and done a fair amount of supplemental reading, I figured Turning Point—a collection of Miyazaki interviews and articles spanning 1997 through 2008 and newly translated by Beth Cary and Frederik L. Schodt—would probably be a rehash of the similar. I presumed it would be a book for Japan or anime specialists. On the back cover there’s even a quote from the L.A. Times: “Essential reading for anyone interested in Japanese or Western animation.” However, this statement is entirely too narrow and ultimately misleading.

In fact, the book (which is a sequel to Starting Point: 1979-1996, also translated by Cary and Schodt and now available in paperback) is less about animation and Japan than it is the human condition and those existential questions that keep you awake at night. Miyazaki, at one moment reserved and the other candid, plunges fearlessly into complex, introspective and intellectual issues about human’s relationship with education, child-rearing, philosophy, history, art, environmentalism and war (to name a few).

He does this with a sprinkle of romanticism and a dusting with realism. Using his seemingly continual dissatisfaction with the world, Miyazaki aims to positively spark change and inspire. He insists that his films are not just flights of fancy; rather, he makes them to motivate the next generation to improve the world. “Children learn by experiencing…it is impossible to grow up without being hurt,” he writes. “Experiences like: accepting the duality of human nature, the importance of grit, conviction, and perseverance, and respecting nature and the land….For children willing to start, our films become powerful encouragement.”

Although his films are supposedly aimed at children, many of his themes and messages ring true for adults. When discussing morally ambivalent characters in Princess Mononoke, he states: “Even if people think things aren’t quite right, they still carry on and follow orders because it was decided by the organization…if we disown this kind of person, we would have to disown almost all human beings!” These kinds of harrowing truths are discussed throughout. After all, with each generation problems are born anew. Forests are still being cut down. Waters polluted. Wars raged. Yet, despite this grim reality and the cyclical human condition, Miyazaki insists that struggle must continue. Humans cannot help but struggle and strive. For him, this was the message in the film: Simply, “live.” No matter what the conditions.

Throughout this retrospective Miyazaki’s anxiety over current affairs is tangible. Repeatedly, he wonders how “as adults we must respond to our children’s question of how to live on a planet that is burdened by such problems.” He can find no answer, but to him passion is key: “Young people have no motivation to carve out their own lives the way the heroine [does]. Even if I depict the growth of a person, it is dismissed as ‘just a movie.’ When I was young, poverty encouraged us to have a passion for life.”

Later he goes on to insist: “Our films won’t be relevant if they only emphasize that all will turn out well as long as they have a positive attitude, full of cheer and vitality.”

This work also reveals Miyazaki’s fickle, contradictory, stubborn and downright grueling nature. For example, he speaks at length of how parenting “should be done” even though he admits he was a reclusive and distant father, seeing his children mainly on weekends. He also speaks of his disdain of virtual video game culture—although Studio Ghibli subsequently helped produce the PlayStation 3 game Ni no Kuni. You also see Miyazaki as a taxing taskmasker who pushes his employees to the limits. Someone exacting—and probably downright mean when under a deadline. But, as Miyazaki says about his films, he wants to “shows both sides of things—the good that is always accompanied by the bad.”

The takeaway of Turning Point is not that it offers conversation about the animation process, character design, or other technical aspects. Rather, it’s a book that encompasses those murky recollections, hopes, fears and other musings that become inspiration for film. It’s a work that crosses time and disciplines, and like Miyazaki’s films, spirits you away into a world of joy and sorrow, happiness and beauty, ignobility and aestheticism. With wit and humor, Miyazaki offers insight from his long career with every turn of the page. And these aren’t even grand, sweeping statements. Rather, like an unforgettable sunset or the first time a cooking experiment came out well, Miyazaki discusses experiences that leave you unexpectedly changed. As he says: “Small daily occurrences give added meaning to our lives.” Anyone who has watched his movies know his uncanny power to transform the everyday into the magical. Turning Point is an affirmation of just that.

For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.