JQ Magazine: JQ&A with Manga Translator Zack Davisson on Shigeru Mizuki

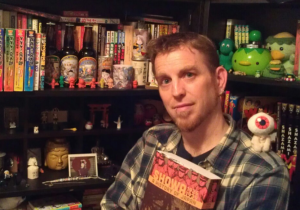

“All of JET is fond memories for me. I loved it. Kansai was the perfect area. Nara, Osaka, and Kyoto were all in easy reach so I had the best of everything. I lived in ancient and traditional Japan, but had wild and modern Japan nearby anytime I wanted. I did everything I could possibly do, went everywhere, tried everything—it changed my life.” (Courtesy of Zack Davisson)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently seeking opportunities with publications in New York. You can follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and board gaming on Twitter @brittlejules.

A scholar, author and translator of Japanese folklore and ghost stories, Zack Davisson (Nara-ken, 2001-04; Osaka-shi, 2004-06) joined the JET Program in 2001 with some basic Japanese knowledge and a strong desire to learn much more. After spending five years on the program, he remained in Japan to acquire a master’s degree in Japanese studies while writing freelance and translating for Osaka University.

The theme of Japanese ghosts running through Davisson’s writing and translation dovetails the interests of manga legend Shigeru Mizuki, who is famous for the classic series GeGeGe no Kitaro. Mizuki is equally well known in Japan for his autobiographical works about his experiences as a soldier during World War II. A great fan of Mizuki, Davisson now contributes to publisher Drawn and Quarterly’s English adaptations of Kitaro and is the translator of the first volume of Mizuki’s historical manga Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan, released last month in North America.

In this exclusive, expansive interview, Davisson discusses his time on JET, the significance of Mizuki’s supernatural and historical works, and the unique methods and madness of manga translation.

How did you first become interested in learning the Japanese language, and how long have you been studying it? For aspiring translators who are still studying, do you have any advice about textbooks, programs, or techniques?

I actually became interested when I was about 10 years old and my mother took me to see Seven Samurai at a local art theater. I was hooked pretty early—if I you look at my class pictures from that time I am wearing ridiculous Japan t-shirts. I took Japanese in high school when it was offered as a foreign language, but there were only four of us in the class, so it was cancelled—no one was interested in learning Japanese back then. This was the ’80s, so there was no “Cool Japan.” That pretty much ended my language studies for a while.

Decades later when I went on JET, I was useless language-wise. I thought I knew more Japanese than I did, but really just the set phrases and greetings. I was determined to leave JET functionally bilingual, so I just studied as hard as I could from day one, eventually getting my master’s degree in Japan.

My only real advice for people is to go to Japan, and talk and read and practice as much as humanly possible. There is no substitute for immersion and experience. I always say I learned more Japanese at my local bar, the 100 Club, than I did doing my MA. Talk, talk, talk. Read, read, read. Use Japanese as a living language, don’t just study it as an abstract. And, of course, marry a Japanese person. That’s a huge advantage!

When and where were you posted for JET? Could you talk a bit about your time there and what you remember fondly?

I started JET in…I think 2001. Crazy to think it was more than 10 years ago, because it doesn’t feel that way. I was unusual in that I was a 5-year JET that worked in two prefectures. I did three years in Nara and then two years in Osaka. I don’t know if they still allow you to do that. I was one of the first in my prefecture to get that contract extension, and even then there were only two of us allowed to do it.

As for fond memories…all of JET is fond memories for me. I loved it. Kansai was the perfect area. Nara, Osaka, and Kyoto were all in easy reach so I had the best of everything. I lived in ancient and traditional Japan, but had wild and modern Japan nearby anytime I wanted. I did everything I could possibly do, went everywhere, tried everything—it changed my life. And my career; I got started in writing and translating doing articles for my prefectural newsletter, then moved on to publishing magazine articles for Kansai Time Out and Japanzine. And now I have my Shigeru Mizuki translations out and my book, Yurei: The Japanese Ghost, coming next year. I owe all that to JET and the people I met on JET.

In what ways did you become involved in your community?

I wasn’t a big community person, other than I threw myself into every matsuri I could. I was fascinated with Shinto festivals, especially the big, loud, and dangerous ones. Anything fueled with alcohol and adrenaline. I did the Okayama Hadaka Matsuri four times and brought the magic sticks out twice. I carried this massive mikoshi in a little village in Nara every year. In Osaka, I carried these giant, flaming torches in the Taimatsu Matsuri for my town. I loved the primal nature of these matsuri, the physicality and closeness to the gods—it’s something we’ve completely lost in the U.S. In our quest for safety and comfort we’ve lost something intangible. Something Joseph Campbell would have recognized and appreciated.

Other than that, I was a regular at a local bar, the 100 Club in Osaka. A different kind of community, but that was another life changer. I’m still friends with my pals from the 100 Club and we even got matching tattoos. Not quite as sweet as volunteering at the local children’s eikaiwa, but there it is.

Do you have any favorite kaidan (ghost stories) that originate from there?

Nara is old and full of kaidan. The dragon’s cave in Muro. The oni’s kitchen and toilet in Asuka. And Shigeru Mizuki’s own Sunakake-Babaa hails from Nara. Osaka is just as good, although with more modern hauntings. My friends all knew I was fascinated with ghost stories and mythology, so they took me out to haunted places, bars, alleys, etc….what they call yurei spots, I soaked up as much folklore as I could.

My favorite is definitely the oni’s kitchen and toilet in Asuka. That’s just fantastic—the place where the oni waylay travelers and cook and eat them, then the specific place where they poop them out.

How were you first exposed to kaidan?

This goes back to me as a little kid again. I was always interested in fantasy, fairy tales, ghost stories, mysterious things, cryptids, etc….I got this set of Time-Life books on monsters and magic in the world. (From my mother, again, shaping my future life. Be careful, parents! You never know when a stray movie or book will determine your child’s life path!) Anyways, these books had a few Japanese stories, like Oiwa and Yotsuya Kaidan. That was really my first exposure. I was fascinated because they were so different from everything I knew.

When I came to Japan on JET I gravitated to the ghostly, and started digging in. I discovered Lafcadio Hearn, which was a huge influence. I read everything I could in English, and then hit a wall where I realized if I wanted to keep going I would have to master Japanese.

You post many short kaidan story translations on your website Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai. Do you make and post these translations for practice or amusement? Or is it in some way related to your other Mizuki translations?

They are only related in that they are all Japanese folklore. And I do my translations for many reasons, including practice, but mainly because I enjoy contributing to the world’s knowledge pool on all this cool stuff. There is still so much that has gone un-translated, and I like making that accessible

I started the website mainly as a place to stick some of the translations that I had done for my MA degree. It was pretty meager in the beginning. I was surprised when people started reading, then a hundred, then a thousand…and now up to over three hundred thousand people that have read my site. I really had to up my game as the site got more popular.

What shocks me is that so many of my fans aren’t even native English speakers. They’re people who are interested in Japanese folklore and speak English, but not Japanese. I have readers from Pakistan, from Russia, from Turkey, from Brazil, all over Europe, Kenya…I get emails from all over the world. It’s pretty incredible.

And yes, for practice, because like everything, translation is a skill you need to keep working at in order to not get rusty. And sometimes it’s for a project—if you notice I am posting a bunch of stuff on a specific theme, then I am probably working on something in the background.

Mostly, I do Hyakumonogatari.com because I love it, though. I wouldn’t do it if I didn’t love it.

At what point did you decide to make your Japanese skills a part of your career? Had you been interested in translation early on?

I decided to be a translator when I was in Japan working on my MA—and specifically Shigeru Mizuki’s translator. That was a goal I set for myself way back then. I thought there was all of this wonderful stuff with no English translation, and I wanted to be the one to bring it over. I used to talk about it in Japan all the time, so much that my friends got sick of it. They’re pretty excited to see my first translated volumes released. I think they are sticking a copy up on display at the 100 Club to show dreams can come true, from time to time.

What did you do immediately after JET? At the time, did you see yourself where you are today?

Immediately after JET I stayed in Japan working as an elementary school English teacher, and doing some freelance magazine work and translation and writing for Osaka University. By that time I had met my now-wife, Miyuki, and we were going through the long process of getting her fiancée visa so we could head back to the States together.

I stayed in Japan until my contracts finished and her visa was secured, then we came back to the U.S. The economy was bad, so I took what jobs I could—there were some lean and miserable years. But I tried to push forward, to build my writing/translation resume, and work on finishing Yurei: The Japanese Ghost.

What kind of translations have you completed in the past? Are they all literary translations? Which ones have been or will be published?

Up until now most of my published translations have been academic, done for Osaka University where I had a contract. I worked on a textbook called Keywords in Use and some of their language-learning software.

Other than that, it has been for my own purposes on my website Hyakumonogatari.com, or at various private requests. I love American comics, and I do translation and research for a couple of different comic writer/artists when they want to stick Japanese flavor into their comics. For example, I work with Tony Harris on Roundeye and Brandon Seifert on Supernatural Geographic. Also, I did the TV special for National Geographic, Okinawa: The Lost Souls of Japan, which involved some translation work and research as well as my on-camera appearances.

I have done a few unpublished manga translations too, for practice and to pitch to publishing companies. We’ll see if any of those see the light of day. I always hope. And I have a few secret, unannounced projects that are definitely coming, but I can’t talk about.

How were you first exposed to Shigeru Mizuki?

It’s hard to be in Japan and NOT be exposed to Shigeru Mizuki! He’s everywhere! I remember being fascinated by his characters and by Kitaro, even though I had no idea who or what they were. At first, my Japanese ability wasn’t good enough to penetrate the mystery, so my main knowledge of yokai came through Lafcadio Hearn, and Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli.

It really took my wife, Miyuki, to introduce me to Shigeru Mizuki. She thought if I liked ghosts and yokai that I would love his comics, so she bought some for me out of the blue. And I was completely hooked. After that, I bought and read as much Mizuki stuff as I possibly could. I even travelled up to Kyoto to meet him at the World Yokai Conference. And I did get to meet him, although briefly.

How did you come to write a translation of Showa: 1926-1939? Was it of your own initiative or Drawn and Quarterly’s? If it was your decision, how did you go about having it published?

I had been pitching Shigeru Mizuki to different companies for a few years, mainly a translation of his Tono Monogatari. I thought that would be an approachable introduction to his work for Western audiences—it’s self-contained, has a nice literary provenance, and is just a beautiful, weird comic. But no one was really biting. Some people were interested, but it never went further than emails back and forth. I didn’t think of Drawn and Quarterly, for whatever reason. Then they put out Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths, which won the Eisner Award that year, and I found out they had the rights to publish Shigeru Mizuki’s works.

I basically just sent them a cold letter saying how thrilled I was that they were putting out his work, and that I would love to be a part of it if possible. It was lucky timing—they already had Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths, NonNonBa, and Kitaro translated, but were in the market for a new translator. I did a 100-page test translation that they compared against their current translation, and they liked it and gave me the job. I think they were impressed with the passion I brought to the project as well as my abilities as a translator.

I was surprised when they told me the next book would be Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan. Because I identify Shigeru Mizuki so strongly with yokai, I would have never thought of doing his war comics. But Showa is an amazing and important comic—possibly his magnum opus—and I was thrilled to take it on. Thrilled and daunted. It’s a heavy work.

Could you tell us a bit about Showa 1926-1939 and Mizuki’s experiences in World War II?

You have to read the comic! Seriously, it is a long and incredible journey, and I wouldn’t want to spoil the story for anyone. But I can tell you some of it.

Lost most young men his age, he was drafted. He was a terrible soldier; obstinate, lazy, insubordinate. His own stupidity got himself shipped to the front in New Guinea—what he calls “the greatest mistake of my life” but in truth is probably one of his defining moments. He was just as useless in Rabaul, and was beaten on a daily basis. Terrible things happened to him there. His squad got wiped out. He caught malaria. He lost his arm in an air raid.

And also wonderful things. He befriended the local Tolai tribe, a relationship that lasts to this day—they have a road named after him in Rabaul. It’s such a powerful story. I’m not ashamed to say that I was so involved in it when I was translating it that I got weepy at more than a few parts.

If you’ve read Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths you’ve seen some of it. He fictionalized some of his experiences for that comic. But this is the real thing.

It’s funny—I just started watching the TV show The Pacific and it struck me how connected the two are. If you just flip the camera away from the Americans and show the Japanese soldiers, then you have some of the books of Showa. Except instead of crazed, fanatical soldiers willing to die for the emperor, you get to understand just how afraid and desperate the Japanese soldiers were.

What particular aspects of the original text did you find most challenging to translate? What did you spend the most time on? Were there any particular areas where you feel something was lost and unable to be rendered into English?

By far the most challenging was the military and political lingo. Nothing in my Japanese studies had prepared me to name the different classes of battleships, or the obscure political theories and parties raging around Japan at the time. I really couldn’t have done it without my wife. She became my assistant, looking up the kanji and making lists for me. And that was tough work. She is a native Japanese speaker, but there was plenty of kanji in there she couldn’t read or didn’t understand. This is a high-level comic.

Then, I had to match everything against Western naming conventions. World War II is heavily studied, and most things have already been named—specific battles and theaters of war and such. And many famous speeches have already been translated and become iconic. All of that had to be taken into account. And then there was the Chinese side…whew! All of the Chinese names and places had to be researched.

On top of that, everything has to fit into a predetermined space—the dialog box is the bane of every manga translator. With a book you can always add more pages, but not with comics.

Japan’s actions in World War II are still sensitive topics today. Earlier this year the education board of a city in Shimane Prefecture asked its elementary and middle schools to limit access to Barefoot Gen, a famous autobiographical manga portraying terrible wartime tragedies before, during, and after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, in primary school libraries after a complaint about its false portrayal of the actions of the Japanese troops during the war. Has Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan received similar criticism or censorship? What about Mizuki’s other autobiographical works?

I was very much thinking about that when I saw the news about Barefoot Gen, as well as the controversy regarding Miyazaki’s new film The Wind Rises. The timing behind that news and the English publication of Showa feels like zeitgeist.

Obviously, WWII is still a controversial topic in Japan today. There is a small but powerful lobby that would like to sugarcoat what happened and write their own pleasant history. This is nothing unusual. Many groups in the U.S. like to do the same thing on various topics. And that is part of why Shigeru Mizuki wrote Showa to begin with.

Make no mistake: Showa is a big, fat, finger-pointing at Japan for what happened during WWII. I get asked all the time about how critical Shigeru Mizuki was, or if he tried to make Japan seem heroic or victimized. All I can say is—read the book. It’s all there. The abuse of China and Korea. The Rape of Nanjing. The serial killers created by the war.

[Mizuki] wanted to educate the modern Japanese children—the ones who grew up post-war and never knew what the generation before them had survived—about what had really happened, in the hopes they would appreciate what they had and never repeat the same mistakes. I’ll never forget what my wife said while we were working on the comic together—“I finally understand why China hates Japan so much.”

But it is also a balanced, accurate account. Mizuki is angry at the war and the suffering it caused, but he presents the facts and circumstances untwisted. In fact, the academic text Controversial History Education in Asian Contexts singles out Showa: A History of Japan as the most unbiased and factual of all of Japan’s various manga accounts of WWII.

That said, there is also the difference in that Shigeru Mizuki is still alive, and one of the most honored human beings in the country. All of Japan has been busy celebrating him for the past year [he turned 90 in 2012—Ed.], and I don’t think anyone is stupid enough to attack one of his books now. Barefoot Gen author Keiji Nakazawa died a few years ago (2010), and so his work is easier to mess with. But no one is going to lead an assault on the living Buddha that is Shigeru Mizuki.

Although, frankly, I wouldn’t mind if someone did try to ban it. Nothing like a little controversy to make people aware of a comic and drive up sales!

You also contributed to Kitaro, the new translation of Mizuki’s GeGeGe no Kitaro. Could you talk about your involvement in the translation and how much of the final product was a team effort?

All manga translation is a team effort. People only see the final product, and aren’t aware of the process it takes to get there. There is usually an initial “rough translation,” then that rough translation is adapted and smoothed out—sometimes by another person entirely, because the same skills that make you a translator don’t necessarily make you a good writer. Personally, I do those two stages by myself because I am a writer as well as a translator. Then an editor works over the script, and, in the case of Showa, a fact checker, and we go back and forth massaging it until it is perfect.

With Kitaro they were up to the editor stage, and brought me in just to do a little fine tuning, clarifying some of the phrases and things like that. I also did a bunch of the background noises—monster growls and bird flapping and stomping and all of that. The Foley work. That’s actually one of the toughest parts of translation, because Japanese and English onomonopias are so different. You pretty much make things up. Fortunately, I have a lifelong background in reading American comics so I have a solid mental dictionary of sound effects. Someone can say “snikt” or “bamf” to me and I know exactly what they are talking about.

My biggest contribution to Kitaro is largely invisible, though. The translation had put all of the yokai names into English—Daddy Eyeball, Rat Man, Sand-throwing Hag, etc.…I am of the firm opinion that names are names and shouldn’t be translated. For example, my wife’s name Miyuki could be translated into “Beautiful Snow,” but it isn’t. I made my case with D&Q to keep the yokai names in Japanese, and they agreed. That’s what led to me writing the yokai glossary for Kitaro as a compromise, which was very well received.

Do you feel that Mizuki’s autobiographical portrayals of World War II and his imaginative fictional work on yokai relate to each other in a meaningful way? How?

That’s tough to say. He blurs lines between autobiography and fiction. Onwards Towards Our Nobel Death and NonNonBa are both fiction, albeit based on facts. And he wouldn’t consider his folklore work to be fiction. He is on record as a firm believer in the spiritual world and yokai. In fact, he encounters several yokai in Showa: A History of Japan, including one that saves his life on the island of Rabaul.

Even then, his fiction work serves different purposes. His work with his character Kitaro ranges from the outright goofy, like Kitaro versus the Yokai Ramen, to making a specific political message, like when Kitaro rallied the Japanese yokai to fight against the American invaders in Kitaro’s Vietnam War Diary. He even has sex comics like the teenaged Kitaro in Kitaro Continued. The further back you go in his career, the more his work was purely commercial, trying to pay his bills. Once he got established and famous, he had the luxury to make it personal.

But no matter what the comic or era, they all carry his specific life philosophy—distrust in the establishment, cynicism, pacifism, and his Cult of Laziness that he is well known for. There are entire books in Japan just on his philosophy—he is as famous for that as he is for his comics. If you read Kitaro, the character Nezumi-Otoko is Mizuki’s avatar, his personal mouthpiece, espousing his eternal quest for an easy life. It’s no coincidence that Mizuki chose Nezumi Otoko to narrate Showa: A History of Japan. When Nezumi Otoko is talking, it is really Mizuki Shigeru.

What advice do you have for aspiring manga translators? Do you foresee any growth in the industry?

That’s a tough question. As everyone knows, the manga boom is long over. Most translators are established pros with years of experience and established relationships with companies. It’s a hard business to break into. There isn’t a lot of room for newbies—every year there are more and more people fighting for a piece of an increasingly shrinking pie.

If there is any growth, it will be digital. I know there is some push in that area, but no one really knows how it will go. There are a few companies trying experimental models, like translators working exclusively on a profit-sharing plan, which means if the book doesn’t sell you don’t get paid. Page rates are down, and few people are manga translators full-time. For most it is a second job, and not the main bill-payer.

For advice, I would say practice, practice, practice. Translate something at least every day. Get a hold of some comics that have English translations, then translate the Japanese and compare it to the official English translation. But whatever you do, don’t post them online. Posted fan translations (a.k.a. scanalations) are poison and will get you blacklisted.

Also, look for paid work. I’ve seen a few editors laugh at resumes that are full of “volunteer” translations, but no paid work. Even if it isn’t manga, you need a resume, you need work experience.

Oh, and go to conventions and make contacts. Like much of the modern world, networking counts. It’s much easier to get jobs if people already know who you are.

As a professional translator, what is your opinion of fan-made translations of Japanese manga that are posted to be read for free on the Internet? In what ways do you think they help or hurt the publication of translations?

Absolute evil. They absolutely hurt the publication of translations, and have taken a huge bite out of the industry on the Western side. People don’t understand the behind-the-scenes of what it takes to publish translated manga, and how damaging fan-translations can be. They make Japanese companies wary about doing business with American companies, and many manga creators take it personally. The West is just a drop in the bucket sales-wise for most manga companies; a million copies sold in Japan versus a thousand sold in the U.S. They can easily afford to be picky and cut off access when fans are behaving badly.

That said…I can understand the impulse behind them. People want to read certain things, and not be held captive by what a particular company chooses to publish at any time. I know how frustrating that is. But have some impulse control. And show some respect. If you love manga, have a little care for the actual human beings who created it, ya know? They deserve their due. If you want to read certain comics that badly, learn Japanese. It doesn’t take THAT high of a level to muddle your way through most manga, especially using an electronic dictionary. And you will gain a valuable skill instead of just stealing from hard-working comic creators.

Plus, the translations usually aren’t very good. I’ve seen a few for Shigeru Mizuki and they are awful, subpar amateur work. And like I said…fan translations are pure poison if you have any hope of becoming a professional. Just say no.

Aside from Mizuki’s work, what are some of your favorite manga series and why?

It comes as a shock to most people, but I don’t actually read a lot of manga per se. I read comics, but I don’t differentiate between Japanese, European, and American comics. To me, Mizuki’s Kitaro and Mike Mignola’s Hellboy are in the same category—both brilliant folklore comics. It is irrelevant that one is Japanese and one is American.

Of the stuff I do like from Japan—I love Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys, which is incredibly dense and one of the best comics I have ever read, from any country. His comics Monster and Pluto are also outstanding. Akira Toriyama’s Dr. Slump is another series my wife introduced me to that cracks me up every time I read it. Yugo Ishikawa’s Kappa no Kaikata (How to Raise Kappa) is a series I would love to translate (if VIZ Comics is listening!). It’s weird, but a lot of fun.

What makes a good comic to me? I’m not really sure. I like something unique, something where you can see the hand of the artist, but at the same time I appreciate classical storytelling and craft. Hellboy is a good example of blend. And there has to be something intangible…the hand of a genius. I can’t really put my finger on it, but it’s something magical that speaks to me. Something I find in the works of Mizuki.

For more on Zack and his upcoming works, visit http://hyakumonogatari.com. For more JQ magazine interviews, click here.

Comments are closed.