“J-Boys is a historical lesson for readers of all ages. Although the story takes place 20 years after World War II, Japan is still very much scarred by the war and Oketani mentions how it affected the mindsets of the country’s people.” (Stone Bridge Press)

By Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata-ken, 2008-2010) for JQ magazine. Rashaad worked at four elementary schools and three junior high schools on JET, and taught a weekly conversion class in Haguro (his village) to adults. He completed the Tokyo Marathon in 2010, and was also a member of a taiko group in Haguro.

The 1960s were a decade of enormous change around the world. Although Japan didn’t experience the upheaval some other countries did during that period, for one teenager, the mid-1960s were shaping up to be a different era.

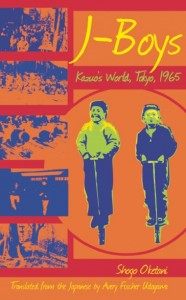

Shogo Oketani’s novel J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965 takes readers into the lives of young Kazuo Nakamoto and, to a lesser extent, his friends—younger brother Yasuo, his friend Nobuo, Nobuo’s older brother Haruo, and Kazuo’s classmate Minoru. As steeped in tradition as Japan is (and continues to be), Oketani paints a picture of a society beginning to be seriously touched by foreign influences. Inspired by the 1964 Olympics in their hometown, Kazuo and Haruo usually head to an empty lot after school to emulate 100-meter champion Bob Hayes (It was Kazuo’s dream to be an Olympic sprinter). And like many young people across the world, Haruo went crazy for a quartet from Liverpool, often singing “A Hard Day’s Night.”

Essentially, J-Boys (which was based on Oketani’s childhood)serves a journey through the ups-and-downs of adolescence while introducing younger readers to Japanese culture and the changing landscape of the country. Kazuo’s father speaks about the rise in TV’s popularity with an air of sadness, blaming it for the loss of a nearby cinema. Likewise, Kazuo feels the new Tokyo (much of it fueled by Olympic-related construction) he sees during his Saturday afternoon walks is not necessary an improved one. Kazuo develops a crush on a girl he’s known for quite a while, but sees a couple of close friends move just prior to the start of a new school year. So he realizes he’s about to embark on an unpredictable journey.

Because the protagonist of J-Boys is a teenager, the book is not surprisingly geared toward younger readers. To familiarize them with Japan, the book includes sidebars with information about Japanese terms and other items readers may be unaware of. While some may wonder why the publisher felt the need to include sidebars with information about rock n’ roll, the Beatles and sumo, many (if not most) readers will appreciate the information in the sidebars. Even readers who have spent time in Japan might be unaware of the cultural references Oketani uses in the book, such as kamishibai and Sarutobi Sasuke.

J-Boys is also a historical lesson for readers of all ages. Although the story takes place 20 years after World War II, Japan is still very much scarred by the war and Oketani mentions how it affected the mindsets of the country’s people. When Kazuo’s class refuses to drink the disgusting miruku served during lunchtime, their teacher from the previous year, Mr. Tanaka, lashed out at the students, stating they were privileged to drink milk considering that soldiers during the war had to drink mud. And Kazuo is annoyed whenever he hears adults say “during the war,” a way of reminding Japan’s youth to be grateful for what they have, considering that during the mid-1940s people couldn’t do certain things (such as study or be choosy about their food).

If you don’t feel like Oketani is talking down to you, you’ll enjoy J-Boys a lot. While it certainly isn’t the most informational text about Japan in the 1960s, you’ll definitely learn something from it.

For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

one comment so far...

Hi Rashaad, It was a pleasure for me to translate J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965 by Shogo Oketani, and I am glad you enjoyed reading it. We hope it will open a window on 1960s Japan for the young and the young at heart! Avery