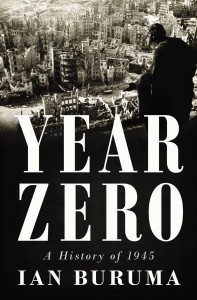

JQ Magazine: Book Review — ‘Year Zero: A History of 1945’

“Though so many of the complexities of World War II and ensuing changes can not easily be summarized, Buruma’s analysis of 1945 provides several enlightening answers that begin to answer the question of how and to what degree a sense of normalcy is achieved after destruction.” (Penguin Press)

By Sheila Burt (Toyama-ken, 2010-12) for JQ magazine. Sheila is a scientific writer at the Center for Bionic Medicine at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. Read more of her writing at her blog.

Consider the following historic events: the bombings of Dresden begin; Franklin D. Roosevelt dies after serving 12 years as president; the B-29 bomber Enola Gay drops “Little Boy” on Hiroshima followed days later by “Fat Man” on Nagasaki, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths, unprecedented instant destruction, and long-lasting illnesses caused by radiation exposure; after six long, bloody years, the Second World War finally ends.

Now consider that all of these events took place in 1945.

Following these milestones in the span of only a few months, how could countries so deeply entrenched in World War II return to any sense of normalcy? How do you rebuild a broken nation?

Author and journalist Ian Buruma explores these questions and postwar disorder in his latest book, Year Zero: A History of 1945.

Writing about a single year (or several months within a single year) is not new—among a few other examples, Bill Bryson recently covered the summer of 1927 in One Summer: America, 1927; in 2010; cultural critic Fred Kaplan analyzed the significance of 1959 in his book 1959: The Year Everything Changed; and in 2005, Mark Kurlansky declared 1968 as The Year that Rocked the World.

For Buruma, a Luce Professor of Democracy, Human Rights and Journalism at Bard College and the author of several books, including the novel The China Lover, 1945 may not be more significant than other years but one of the most groundbreaking for transformations. Rather than focusing on the postwar efforts of a single country, Buruma looks at the countries destroyed or nearly destroyed by the ferocity of World War II, specifically narrowing in on the postwar chaos and change in Europe and Japan. “How did the world emerge from the wreckage? What happens when millions are starving, or bent on bloody revenge?” he asks in the prologue.

To explore and answer these questions, Buruma, who has written extensively about Japan in the past, weaves together several narratives and uses mainly secondary sources to build his narrative. He condenses a tremendous amount of research to write the biography of a defining year.

In addition to exploring the political and social milestones beginning in 1945, Buruma also tells a personal story of his father throughout the book. In 1941, his father was captured during the Nazi occupation of Holland. For much of the war he worked a laborer in Berlin, and by the end of the war Buruma notes his father was one of more than eight million displaced individuals stuck in Germany waiting to go home. This family story gives the book a distinct personal touch; elsewhere, Buruma focuses on larger themes of postwar confusion and progress—the slow rise of women’s liberation movements, the breaking down of class systems, debilitating poverty, and war crime trials (or lack thereof).

While Buruma notes that after the disasters of World War II, most Japanese embraced a “return to modernity, which they associated…with America in particular,” he also explores much darker postwar days as well. The chapters “Hunger,” “Revenge” and “Ruling the Law” particularly support Buruma’s thesis well: the war was over, but uncertainty, radical change, and idealism defined the rest of 1945.

He is particularly convincing when writing about the large-scale misery and poverty that consumed so many following the war. He notes that Milan is described by an observer as “a slice of hell” and in Japan, where civilians had already been barely surviving on extremely dwindling rations, “government authorities were advising people how to prepare meals from acorns, grain husks, sawdust (for pancakes), snails, grasshoppers, and rats.”

In the chapter “Going Home,” Buruma poignantly contrasts his father’s return home to the Netherlands with millions of others who could not return to their countries with ease. For some, he notes, “coming home was a disappointment, or worse.” Buruma notes that outside of the eight million displaced persons in Germany, more than three million individuals in other European countries were left homeless after the war; 6.5 million Japanese—half of them civilians—were stranded in Asia and the Pacific; and more than one million Korean workers were still in Japan.

Though so many of the complexities of World War II and ensuing changes can not easily be summarized, Buruma’s analysis of 1945 provides several enlightening answers that begin to answer the question of how and to what degree a sense of normalcy is achieved after destruction.

For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.