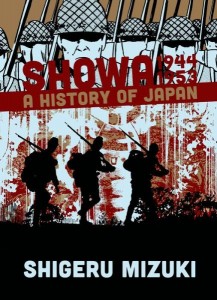

JQ Magazine: Manga Review — ‘Showa 1944-1953: A History of Japan’

“If you enjoy or are interested in manga and history, or if you appreciate such excellent works as Maus, Persepolis or Barefoot Gen, then this series is a must-read.” (Drawn and Quarterly)

By Julio Perez Jr. (Kyoto-shi, 2011-13) for JQ magazine. A bibliophile, writer, translator, and graduate from Columbia University, Julio is currently working at Ishikawa Prefecture’s New York office while seeking opportunities with publications in New York. Follow his enthusiasm for Japan, literature, and comic books on his blog and Twitter @brittlejules.

Showa 1944-1953: A History of Japan is the third volume in a four-part manga history of the Showa period by eminent manga artist Shigeru Mizuki. (If you’re new to this series, check out JQ’s reviews of the first and second volumes here.)

Since I have already sung the praises of Mizuki’s excellent blending of realistic and comical art and storytelling as well as the top-notch translation by JET alum (and JQ interviewee) Zack Davisson (Nara-ken, 2001-04; Osaka-shi, 2004-06), I have decided to focus this review more on unpacking some of the contents of volume three and providing you with additional resources to look into if you wish to expand your knowledge about any of the topics that appear in the manga, including several wartime tragedies and the postwar occupation of Japan by the Allied Forces.

This volume focuses primarily on the grim latter years of World War II in the Pacific Theater. Despite the fact that Japan’s resources are running far past thin, the government and military persisted in continuing the conflict. This manga puts the spotlight on the plight of soldiers who have become the least important resource to the Japanese government, “Human life is the least valuable resource in the Japanese Army,” Mizuki writes. “Any suggestion that soldiers’ lives have meaning is tantamount to cowardice and treason. Soldiers are tools to be used. And the command’s greatest fear is that soldiers will flee from the enemy—or worse, surrender. They need them more afraid of dishonor than death.”

Mizuki portrays several historical events and some of his own experiences that illustrate this philosophy among the commanding officers, and how all ranks are pressured into seeking a noble death over the shame of capture or surrender. These values began to direct the military strategies that would lead to the kamikaze special attack units and human-manned torpedoes. In the face of defeat, it became nobler to die than to survive, and as a result many survivors were punished or mistrusted as if they had done something wrong.

One example was the major losses at the island of Saipan, which ended in the largest banzai charge in history, leaving 4,300 Japanese soldiers dead on the beaches. The results of the conflict are astounding: “There were about fifty thousand Japanese soldiers and civilians on Saipan. The U.S. takes fewer than a thousand prisoners. Many who did not die in the banzai charge throw themselves off cliffs.” Civilians were tragically involved in many conflicts; in Okinawa, for example, “General Mitsuru Ushijima commands seventy thousand soldiers…he also has twenty-five thousand civilians, called the Iron and Blood Volunteer Units, and over two hundred female high school students called the Lily Corps.” Mizuki shows later that even the Prime Minister Suzuki was shocked to see that sharpened bamboo sticks pass for weapons in these volunteer units.

These desperate military tactics are considered by many to be among the darkest and most controversial subjects of world history, and for this reason have been given much study and reflection. For those interested in the Japanese historical background that gave rise to the aspirations for death over surrender, I recommend looking into The Nobility of Failure by Ivan Morris, a book that explores self-sacrifice and the tragic heroes of Japanese history and literature from heroes such as Minamoto Yoshitsune, of the Heike Monogatari, to Saigo Takamori, who was known as the last true samurai. In the final chapter, Morris also examines the tragic history of the kamikaze pilots of World War II.

For more perspectives in yet another medium, the 2007 documentary Wings of Defeat features interviews of four trained kamikaze pilots and U.S. Navy veterans. And for more of Mizuki’s land-based wartime perspective on soldiers compelled to die in battle, check out his manga collection Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths, also published by Drawn & Quarterly.

In addition to the harrowing portrayals of the many soldiers who became victims of the war, Mizuki’s own painful and tragic experiences appear in this volume. When it comes to his own life, Mizuki has a unique style of using his familiar silly comical art and narrative structure to deliver what must be raw memories for him. Whether this is his own way of coping or if it’s done for the reader’s benefit is unclear, but the contradiction enhances the pages in striking ways. After to the loss of his entire unit and friends, there is also the incident in which he loses his arm. Mizuki is lucky enough to survive, but wherever he and the other survivors go, they’re treated like they did something wrong and deserve to be punished for having lived.

Mizuki attributes his survival to blind luck and partially to his strong constitution, forever seeking out his next meal. But he also credits a few supernatural occurrences where we again see the influence of yokai in his life. Then there is his interesting relationship with the natives of Rabaul, who quickly accept his eccentricities and come to look on him with affection as one of their own. Mizuki owes a great deal to the natives of Rabaul, who supported him between severe bouts of malaria and sickness from poor medical support.

This chapter of history also includes yet another well-known and dark subject, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Compared to the wealth of information Mizuki provides about nearly every significant incident or development in the war, it is somewhat surprising that he does not devote much attention to the atomic bomb. Perhaps it is because it is a mammoth topic which has already received much literary and historical attention, or perhaps because it is too removed from his own experiences to comment on. If you wish to expand your reading on this topic, I recommend Hiroshima by John Hersey, which has firsthand accounts of six survivors of the bombing. Of course, there is also Keiji Nakazawa’s landmark manga series Barefoot Gen, which focuses on life in the wake of the bombing.

After the war, the narrative continues to the Occupation of Japan by the Allied Forces and the role of General MacArthur and the Allied Nations in composing Japan’s constitution, and also their censorship practices to suppress any preference for the old regime or revenge-driven themes in media such as those that appear in the revenge of the Forty-seven Ronin story. We follow Mizuki back to his hometown, which he never expected to see again, and witness some of the difficult challenges that await war veterans, such as meeting the parents of sons who did not return.

The next years are filled with more difficulties with money and procuring food as well as political protests and censorship by the Allied Forces, labor parties, and Communist-leaning organizations. A new world order is forming, and the Korean War highlights the Cold War conflicts between the USSR, China, and the U.S. that other countries find themselves embroiled in. If you are interested in further reading on the Occupation of Japan, I recommend Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II by John W. Dower.

Meanwhile, Suzuki aimlessly travels Japan looking to find work, begging for money, squatting with other veterans in abandoned buildings, and working as a fishmonger before finally earning enough money to put himself through art school. This will lead to his work in kamishibai and then the new thing in Tokyo: comic books.

If you enjoy or are interested in manga and history, or if you appreciate such excellent works as Maus, Persepolis or Barefoot Gen, then this series is a must-read. The fourth and final volume of this epic history, Showa 1953-1989, will be released in April, and is available now for pre-order at a reduced price on Amazon. If you can’t wait to read more of Mizuki’s other works, Drawn & Quarterly has already published his award-winning Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths, and his yokai-focused cultural landmark manga Kitaro and NonNonBa.

For more JQ magazine book reviews, click here.

Comments are closed.