Kyodo News “Rural JET alumni” series: Nic Klar (Niigata)

News agency Kyodo News has recently been publishing monthly articles written by JET alumni who were appointed in rural areas of Japan, as part of promotion for the JET Programme. Below is the English version of the column from October 2013. Posted by Celine Castex (Chiba-ken, 2006-11), currently programme coordinator at CLAIR Tokyo.

********

Originally from Australia, Nicholas Klar (Niigata-ken, Itoigawa-shi, 1995-97) wrote the book “My Mother is a Tractor” about his life as an ALT in Omi, Itoigawa, Niigata-ken. After JET he worked for many years as a college counsellor and History teacher in international schools before returning to Japan to live. He now runs a small business in the Japan Alps, “Explore the Heart of Japan” as well as a popular travel website (http://myoko-nagano.com).

Remember that here all is enchantment, – that you have fallen under the spell of the dead, – that the lights and the colours and the voices must fade away at last into emptiness and silence. –Lafcadio Hearn

It was a stark winter’s day as usual in Niigata-ken, grey like sodden blanket. Not one that I had set out on seeking ghosts, but it suited the mood. As I changed trains in Naoetsu for Ōmi the old tempura stand I had been hoping for a snack at was still there, but today it was closed. It seems even the sturdy yukiguni could not stand the sort of weather that was being hurled at them this winter from across the Japan Sea. I settled into my seat, its soft orange covers familiar like an old friend, and waited for the delayed departure. I scrubbed the mist from the brown streaked windows with my hand as the motor idled and the minutes slipped by. Outside schoolboys in their traditional Prussian kit seem oblivious to the biting gusts of artic-like snow. Eventually with the sound of the station attendants whistle the doors snapped shut and the blue and white carriage groaned away from the platform.

As we crossed over the dark frigid waters of the Himegawa almost an hour later I grew excited. I hadn’t been back to the haunts of my old town for years. It was an unplanned visit and no-one really knew I was coming. I looked over for the local chugakko as the train passed by, obscured now by the construction of the new Hokuriku shinkansen. Framed behind those were the mountains I had loved so much. So many times I had taken my bike up into those North Alps making new discoveries, getting lost in the awesome beauty of its nature. Days of sunshine, days of rain. How I missed them. And the ghosts that inhabited them.

To the right there was a slight glimpse of my former apartment block. Not mine anymore, not for many years. In fact I think it now lays empty, apart from maybe a ghost or two, as the town depopulates. Tall, grey, forbidding – once referred to by a friend as, “…classic 1950’s communist Romanian style architecture”. The memory of that remark brought a brief smile to my face. Yet, it is the only place I will ever live in that has a sea view at the front and the mountains at the back. Grand views of God’s great vista on tap.

When the doors clunked open at Ōmi eki it was if nothing had changed. The chimes rang the same they had all those years ago and the black asphalt platform lay several centimetres thick with windswept snow. It felt soft under my feet as I began my ascent up the cold cement stairs. Standing in his post was my first metaphorical ghost – Watanabe-san the station master in the same blue-clad uniform, looking not a whit older than when we had last met a few years ago. He didn’t recognise me of course, even though I had taught his daughter at Ōmi chugakko. During my stay many of the station attendants had greeted me by name each time I passed through the gate. The inside of the station was a time capsule still painted the same green, apart from a more modern poster here and there, populated by even more ghosts of my memories. Local oba-chan in the waiting room still sat chatting on wooden bench seats around the kerosene heater behind glass doors. The three old shuttered-up ticket windows still existed – a sad reminder from the more grandiose boom days of Ōmi. Perhaps they were stubbornly retained in the forlorn hope that those times may yet return once again.

“In an emotional sense, though I have left Japan, it will never leave me. […] I will never forget the taste of ramen in old Yamada-sans little shokudo, the refrain of “bai, bai” from the students each school night as I cycled home, nor the sight of thousands of sakura trees in bloom.”

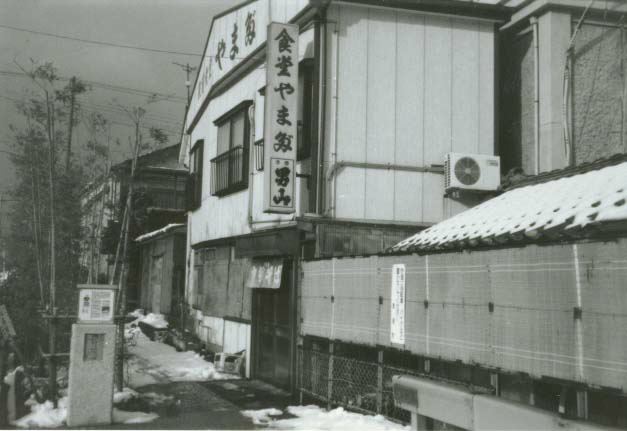

Yamada-san was a kindly old octogenarian who had fed me many oishi bowls of chiyashu ramen during my two years in this little inaka wayside on the Japan Sea. She would dote over me like a worried grandmother and chatter endlessly, not concerned in the slightest that I could hardly understand a word. Even then she was trying to hand the business on, but apparently had no-one to pass it to. She cried the day I told her I was going to leave, and even more the day I actually did. I gave her a framed photo of us to keep and she promised that it would always be ‘her treasure’. Now she was gone, to where I don’t know. If she is not of this earth I wish to visit her memorial, shed a tear, and let her know that I still remember Yamada-san and her kindness.

I checked the bus timetable and find that only a handful of buses from Itoigawa now reach this far every day, perhaps more out of sympathy than practicality. From there it’s only a short amble to the dark forbidding sea and its ghosts leapt at me with all their anger. The towering white-capped waves crashed hard against the triangular breakwater and the wind and snow furiously attempted to blow me back from whence I had come. As I walked hunched along the seafront I noticed that mine were the only footsteps in the snow. A solitary walk, almost like an allegory – a reminder of the days when I occupied this town as its sole foreign resident. Everyone recognised me then. Now it is I who must appear the ghost.

Hungry, I prowled for food and found myself in the little ‘Hapi’ supermarket where I used to shop in those distant days past. Serving me at the checkout was a young lady in her early twenties with the standard greeting, tousled hair and a cherubic face. Obviously one of my ex-students, but not a trace of recognition crossed her features. Inside the genkan the wind howled outside and housewives chattered while I stood eating my cold bento. I plodded toward the old town hall wondering what I would find. What I do find startles me. Nothing. An empty plot. The merger with Itoigawa has consumed a whole swathe of mortar, bureaucracy and more of my personal ghosts. The office where I stood giving my first speech, the desk where I spent my first month, windows from where friends waved to me, the genkan in which the staff stood bidding me banzai on my fateful last day – all gone.

The library and museum still stand adjacent but they too contained ghosts. The buildings had opened during my time in the town. On slow rainy afternoons I would select laser movie discs in the library to watch and when I entered today they all still stood in silent sentinel against the wall. The computer terminals too. I think I had been almost the first to use the internet there, then a very modern concept for an out of the way rural Japanese town.

But now I have to hurry. I bound down the road and up the stairs of the eki toward a waiting train. On the platform near me a high school girl with her high skirt and loose white socks chatted on her keitei. She would’ve been in junior primary or even yochien when I taught her. I climb aboard and the train rocks and speeds me away once again through the elements.

What do I think about now? Sometimes of my fellow teachers, sometimes the old townsfolk and sometimes my perception of what I once had. I somewhat pity those who had been trapped amongst noisy urban megalopolises of the eastern coast, so busy and full their ghosts have no place to rest. I’m sad that being in such a remote place maybe I didn’t develop enough close friendships – even amongst the gaijin scattered throughout the prefecture. It matters little, shoga nai, all will go with their lives and I with mine. The Land of the Rising Sun has graciously accepted us all now over nearly twenty five years on the JET Programme, for better or for worse, and affects us all in different ways.

Do I miss Japan? I sometimes feel that I don’t talk about it or think of it often. And in most ways life has just gone on. My time in the little town by the sea was not something permanent. I have moved on, got married, started a family and hopped across two more countries. It just was a way station on my travel through this earthly existence. In the current bustling city where I live I fret for the slow decline of Ōmi and hope that the imminent arrival of the new shinkansen will bring forth a tide of new settlers and baby-boomer ‘sea-changers’ to reinvigorate the town.

In an emotional sense, though I have left Japan, it will never leave me. I will remember forever the smiles of countless small children and the song of the train whistle from the nearby tracks. I will never forget the taste of ramen in old Yamada-sans little shokudo, the refrain of “bai, bai” from the students each school night as I cycled home, nor the sight of thousands of sakura trees in bloom. And as years pass I ultimately remember Japan each time I stare into the face of my children.

On hot summer nights I sometimes sit on the front porch listening to traditional Japanese folksongs and all the memories come tumbling back once again. If there are still ghosts I am now content to keep their company. I know that in time any distant bad ghosts will fade away, only the good ones will remain, and I will recall the time in Ōmi – my little Japanese town of the blue sea, only with a special fondness. I guess that’s exactly how it should be.

Comments are closed.